Atenism and its Antecedents

Introduction

The-Aten, and its doctrine

Atenism, existed within a brief span-of-time of

Akhenaten broke

with religious tradition and replaced the established pantheon with the-Aten, a

single monotheistic god who was the tangible manifestation of the sun. His

aversion to Amun (who had been the primary state god since the Middle-Kingdom)

and exclusive worship of the-Aten resulted in fundamental changes in religion,

society, writing, art, architecture, and the concepts of kingship.

The motivation

for these dramatic changes have challenged scholars to speculate whether

Akhenaten was an evangelist of monotheism (he was certainly the first to

introduce the belief in a single god) or whether Akhenaten was a politically

astute monarch acting to curtail the extensive influence of the priesthood of

Amun while preserving his kingly authority.

Religious

landscape during the majority of the 18th Dynasty

Solar-Hymns had a cosmic focus and described the sun-god

in relationship to the divine forces of nature and, as Allen (2001b,-p.148) writes, are “inherently polytheistic in

character” - although hymns dedicated to individuals can be interpreted as a

more “monotheistic view of divinity”. Allen explains that a thematic tendency

of Solar-Hymns is demonstrated from the Middle-Kingdom and ultimately

culminated in the Great-Hymn-to-the-Aten. Raver (2001,-p.168) adds that the didactic Instructions-of-Merikare (ruled

during the 1st-Intermediate-Period) refers to “The God” and Lichtheim (19975,-p.106) translate part of the text as “He Shines in

the sky”. Any interpretation of an association from the text within the Instructions-of-Merikare into the-Aten

is tenuous, however the increasing solarization of the established cults is

evident and Aldred (1971,-p.40) summarizes this

as “monotheistic syncretism” of the gods and Re.

For the first

200 years of the 18th Dynasty (Shaw,-2002,-p.481) Amun-Re was

the

primary god of

The-Aten before Akhenaten’s reign

Speculation and

hyperbole has traditionally surrounded scholastic works on the-Aten; Rawlinson

(1886,-p.223) asked if the-Aten and the

religion that Apepi (the last “Sheppard King”) brought to Egypt were associated,

Weigall (1912,-p.37) proposed that Tiye had

adopted the solar-deity the-Aten in thanks for allowing her to conceive a male-child,

and Aldred (1971,-p.41) views the-Aten as Akhenaten’s

new and revolution religion. Modern knowledge continues to make significant

advances and is more subjective and less speculative; I agree with David (2002,-p.215) and

Schlögl(2001,-p.156) that the-Aten existed as

an unimportant god within the Egyptian pantheon and was attested in the Middle

Kingdom - although it isn’t clear when the-Aten first received a separate cult.

Lichtheim (1975,-p.223) explains that within

the Tale-of-Sinuhe there are references to the sun-disk in relationship to the

12th-Dynasty rulers Amenemhat-I and Senusret-I;

Watterson(2002,-p.62) adds that hieroglyphs used

“for ‘sun’ is

Aten rather than the more usual Re” and that we can textually-date the-Aten to

the 12th-Dynasty.

From Thutmose-IV’s reign (Amenhotep-IV’s

grandfather) we find re-occurring inscriptions referring to the-Aten and this

continued through Amenhotep-III’s (Amenhotep-IV’s father) reign - during this period the-Aten

was identified as a distinct solar-god and differentiated from Re. Thutmose-IV explored the solar aspects of kingship,

especially those related to the sun-god (Bryan,-2001,-p.403) and Berman (2004,-p.3) agrees adding that Thutmose-IV increasingly identified himself with the solar-gods.

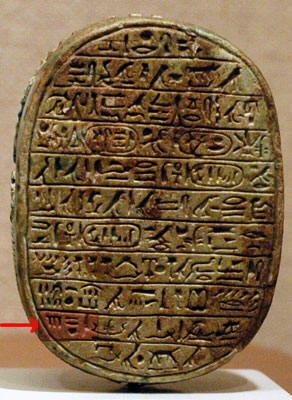

Thutmose-IV associated with the sun-god at iwnw (meaning pillar or - as the Greeks

named it - Heliopolis or the City of the Sun (Allen,-2001a,-p.88)), rather than to Amun-Re. Shorter (1931,-p.23-25) demonstrated the-Aten’s use within

Thutmose’s reign using a scarab inscribed “he (Thutmose-IV)

arouses him self to fight with Aten before him” and “bringing subjects to the

rule of the-Aten forever”.

From Thutmose-IV’s reign (Amenhotep-IV’s

grandfather) we find re-occurring inscriptions referring to the-Aten and this

continued through Amenhotep-III’s (Amenhotep-IV’s father) reign - during this period the-Aten

was identified as a distinct solar-god and differentiated from Re. Thutmose-IV explored the solar aspects of kingship,

especially those related to the sun-god (Bryan,-2001,-p.403) and Berman (2004,-p.3) agrees adding that Thutmose-IV increasingly identified himself with the solar-gods.

Thutmose-IV associated with the sun-god at iwnw (meaning pillar or - as the Greeks

named it - Heliopolis or the City of the Sun (Allen,-2001a,-p.88)), rather than to Amun-Re. Shorter (1931,-p.23-25) demonstrated the-Aten’s use within

Thutmose’s reign using a scarab inscribed “he (Thutmose-IV)

arouses him self to fight with Aten before him” and “bringing subjects to the

rule of the-Aten forever”.

Amenhotep-III

dedicated significant numbers of statues, especially to celebrate his three sed-jubilees

(Bryan,-2001,-p.72),

and Freed (2001,-p.134) postulates whether

this could have been related to his increasing devoting to the-Aten. Later in

his reign a more honest artistic depiction of the aging-king was employed - possibly

concomitant with the eccentric

or baroque representations of Amenhotep-IV

which Schäfer (2002,-p.20) describes as

“expressionist”.

Textual

references to the-Aten are frequent during Amenhotep-III’s

reign; Berman (2004,-p.14) wrote that

“dazzling Sun-Disk” became Amenhotep-III’s

favourite epithet and

The-Aten’s

prominence heightened during Amenophis-III’s

reign, which is demonstrable within the widespread associations to the-Aten; ranging

from day-to-day objects, to significant structures, to international exchanges,

and to naming a daughter Baketaten (Johnson,-1996,-p.78). The-Aten was given a universal context,

possibly attempting to restore the king’s total authorityand with the potential to

threaten Amun-Re's omnipotence as 'King-of-Gods'

(David,-2002,-p.215), yet

Amenhotep-III retained the polytheistic pantheon and stressed

the multiplicity of deities (Horung,-1999,-p.20). His placing hundreds of Sekhmet statues in

the temple-of-Mut

at

It is clear that the role of the sun-god, as the sun-disk

(the-Aten), gradually gained in importance during Thutmose-IV’s reign and assumed a significant role during

Amenhotep-III’s reign, eventually providing

the basis for Amenhotep-IV’s so-called ‘revolution’.

Akhenaten, Coregent and King

Akhenaten, Coregent and King

Amenhotep-IV was the second son of Amenhotep-III and Queen-Tiye

(Dodson-&-Hilton,-2004,-p.114). His

father reigned until at least his 38th regnal year

(O’Connor-&-Cline,-2004,-p.22) and

was buried in WV22

in the

Whether coregency existed with his father remains uncertain

- which makes opinions on the actual length of his reign differ. Scholars

divide into three main ‘schools’; those supporting little or no coregency with a

reign of approximately 17-years (Eaton-Krauss,-2001,-p.48), those supporting a co-regency

of 10-12-years and a reign of approximately 5-7-years (Aldred,-1959,-p.32), and those such as David (2002,-p.214) who are undecided because of a lack of

evidence. Aldred’s later writing reflected a changing opinion and became careful

to accept that coregency was possible (Aldred,-2001,-p.169). Should

Eaton-Krauss’ belief that the coregency is

anachronistic be proven

it will alter the chronology of international-relations (including the Hittites

overthrowing the

David (2002,-p.232) and

Silverman,-Wegner-&-Wegner (2006,-p.29)

concur that Amenhotep-IV’s actions may have

been the culmination of Amenhotep-III’s

identification with the-Aten and even with his deification – which removed the

necessity for Amenhotep-IV to be associated

with Amun-Re as the Son-of-Re; his biological father providing his-son’s divinity and being reflected in Amenhotep-IV’s use of “as my father lives” (Murnane,-1995,-p.76) as a prefix to the-Aten’s

name. David (2002,-p.232)

and Johnson (1996,-p.80) agree that there is evidence to place

Amenhotep-III at Akhetaten towards the end of

his life - which supports a coregency and the-Aten being a continuation of his

theological concepts – although Baines (2004,-p.292)

simply explains this as being part of Amenhotep-III’s

mortuary-cult. Uphill (1963,-p.124) discussed

Heb-Sed festivals, celebrating royal-jubilees, as an example of Akhenaten’s

uniqueness, or even diminishing state of health - Silverman,-Wegner-&-Wegner (2006,-p.30)

are more convincing in proposing that Heb-Sed festivals continued from

Amenhotep-III’s reign into Amenhotep-IV’s reign (initially during Amenhotep-III’s 3rd-regnal

year) without the traditional ‘qualifying period’ of thirty-years as a celebration for the deceased/deified

Amenhotep-III.

On-balance, because of the paucity and ambiguity of supporting

evidence for a coregency, I concur with the opinion that Amenhotep-IV succeeded on his father’s death and agree with Baines

(2004,-p.271) who wrote “there was no

chronologically or historically significant phase of coregency”.

Was the-Aten

expedient..?

Amenhotep-IV remained at Thebes during

the early years of his reign (David,-2002,-p.217) and quickly took the first-steps towards

religious change – these were evident from the numerous talatat blocks used to

construct temples dedicated to the-Aten (Gem-Pa-Aten, Hut-Benben, Rud-Menu and

Teni-Menu (Wilkinson,-2000,-p.164)). Blocks from Gem-Pa-Aten were inscribed with

"expressionistic" scenes that broke-away from the established

artistic tradition and Schlogl (2001,-p.156)

explained that the artistic change was concomitant with religious change.

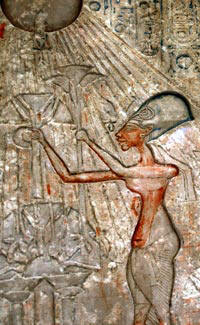

The-Aten’s iconographic representation was initially

in falcon-headed human form with a sun-disk on his head (Wilkinson,-2000,-p.240). This

representation (Schlogl,-2001,-p.156) was abandoned in favor of the solar-disk as

an orb (with a classic uraeus) emitting anthropomorphized rays that ended in

human hands giving "life" exclusively to Akhenaten and Nefertiti (the

great royal wife) and we might view this group as a replacement for the Theban

triad (Amun, Mut, and Khonsu).

The-Aten was the light radiating from the sun and

Schlogl’s (2001,-p.156) opinion is that

it should be more correctly

pronounced Yati - (Hornung (1999,-p.50) adds

that Akhenaten’s actual name was probably Akhanyati

and

Griffiths (2001,-p.479) attempt to rationalize

the iconography as a “compassionate ethic” where the sun-rays are “helping

hands”.

The-Aten’s iconographic representation was initially

in falcon-headed human form with a sun-disk on his head (Wilkinson,-2000,-p.240). This

representation (Schlogl,-2001,-p.156) was abandoned in favor of the solar-disk as

an orb (with a classic uraeus) emitting anthropomorphized rays that ended in

human hands giving "life" exclusively to Akhenaten and Nefertiti (the

great royal wife) and we might view this group as a replacement for the Theban

triad (Amun, Mut, and Khonsu).

The-Aten was the light radiating from the sun and

Schlogl’s (2001,-p.156) opinion is that

it should be more correctly

pronounced Yati - (Hornung (1999,-p.50) adds

that Akhenaten’s actual name was probably Akhanyati

and

Griffiths (2001,-p.479) attempt to rationalize

the iconography as a “compassionate ethic” where the sun-rays are “helping

hands”.

Amenhotep-IV (‘Amun

is satisfied’) changed his name to Akhenaten (‘beneficial to the-Aten’) (Eaton-Krauss,-2001,-p.49) by his

5th-regnal year and the-Aten was

given a royal titulary and its name was written within cartouches like a royal

titulary. About the same time a new residence for the-Aten and the court,

untainted

by any previous association with the traditional gods, was

established (midway between

Akhenaten, his-father, and his-grandfather each rejecting the

traditional royal marriage and David (2002,-p.214]

suggests that this was calculated to curb the power of the of Amun-Re

administration – which was led by First-Prophet-of-Amun May (Redford,-1963,-p.1) -

who’s support was traditionally required in the selection of an heir. The-Aten

cult’s development undoubtedly led to tension with the priesthood of Amun-Re;

in Akhenaten’s 5th-regnal year he declared

that the-Aten would no longer tolerate the existence of any other gods (David,-2002,-p.218) and

the priesthoods of other gods were disbanded and temple-incomes were diverted

to the-Aten. A fragment of text from

Between the 9th and 12th-regnal years the-Aten received its final didactic name

which eliminated all traces of the old polytheism - ‘Life to Re, ruler of the

two horizons, who rejoices in the horizon in his name Re, the father who is

come as the-Aten’ (Schlogl,-2001,-p.156).

Watterson (2002,-p.64/8)

extends a plausible suggestion that the-Aten and Akhetaten (and family) are

better described, in totality, as henotheistic because it was Akhetaten who was

worshiped by the people as a living-god and he conversed exclusively with the-Aten

- I suggest that this may be interpreted as being so isolationist and the-Aten

remote and paradoxical from traditional beliefs that religious

pluralism

was inevitable – which resulted in the-Aten’s alienation and rejection.

We cannot fully determine the true-motivation of Akhenaten - or his-father or his-grandfather

- in promoting the-Aten to such a favoured status within the pantheon. Was

their intention to ‘promote’ a favoured god who had offered some benefit –

which in turn became Akhenaten’s passion – or was the motive more of a cynical

attempt to control Amun-Re’s priesthood? I judge that the wide-ranging

migration to monotheism by Akhenaten must indicate a more religious and intellectual

intention along with expedient political manoeuvring against an overly-powerful

priesthood. Akhenaten introduced significant and shocking changes to an

old-established order, already initiated by his predecessors, and I propose

that his actions were not rash, impulsive, or un-planned reactions but a slow

and careful series of ‘battles’ within a ‘war’ against the establishment of

Amun-Re by the prophet of a jealous god who understood that politics and

religion were indivisible parts of kingship.

The doctrine of Aten

“Eat, Drink, and be Merry”

is how Reeve (2005,-p.141) described the new

religion, adding that it is superficial. I agree that the doctrine was evolving

and was work-in-progress but I view such a light-hearted analysis to be

significantly underestimating the doctrine’s depth.

Hornung (1999,-p.52) wrote that “Akhenaten left no holy scripture”

of the-Aten’s doctrine, adding that texts explain that Akhenaten had placed

instructions “in the hearts of his subjects”. However I disagree that Akhenaten

didn’t have a scripture because texts do partially define Akhenaten’s

teleologicaldoctrine of the-Aten is a

personal reflection of the world through his eyes, which is reflected within

two important texts – the Boundary Stela-‘M’ at Akhetaten (unfortunately this Stela, which

had deeper insights into his motivation, deteriorated badly in antiquity

(Murnane,-1995,-p.73))

and most importantly the Great-Hymn-to-the-Aten

inscribed within Ay’s tomb (Baines,-2004,-p.287) - there are many similar Stelae and Hymns

which echo these texts; I date Ay’s tomb between the 5th-9th-regnal years (using the-Aten cartouches from de-Garis-Davies

(2004c,-plate.XXVII) and Aldred (2001,-p.19)).

Assmann (1995,-p.158) described the doctrine or theology as being

firstly an embryonic treatise (as an evolution of Heliopolitan creation-myths) and

secondly a statement of the world’s harmony – Assmann paraphrases it as

“Naturehre” or a “natural philosophy”. This view is something I wholly agree with.

Akhenaten’s art

depicts a strong acceptance of emotion, scenes are often reflect their

importance to the message rather than the status of the subjects or their

religious importance (Hornung,-1999,-p.47); however I do not deduce a socialization of

art, primarily because Akhetaten’s

androgynousform

continues to dominate and dictate artistic representations, and I choose to

isolate art when rationalizing the-doctrine.

Akhenaten’s art

depicts a strong acceptance of emotion, scenes are often reflect their

importance to the message rather than the status of the subjects or their

religious importance (Hornung,-1999,-p.47); however I do not deduce a socialization of

art, primarily because Akhetaten’s

androgynousform

continues to dominate and dictate artistic representations, and I choose to

isolate art when rationalizing the-doctrine.

Akhenaten

believed that god and the universe were contained within the light emanating

from the disk of the sun

(Silverman,-Wegner-&-Wegner,-2006,-p.37) and the disk was the iconic representation of

the cosmic creator, represented radiating light, balance, and beauty. This

naturalistic focus is acknowledged by all authors and it positively extols a

warm and beneficent deity. The Great-Hymn-to-the-Aten

from the West Thickness of Ay’s unused tomb, is described by Murnane (1995,-p.107/120) and de-Garis-Davies (2004c,-p.16/24-&-p.29/35)

using copies made by Bouriant in 1883 and 1884 (after which significant parts

of it were destroyed). de-Garis-Davies accurately describes the Hymn as being

poetic, dogmatic, and with a strong “teaching” message - I would classify all

of the Hymns as having the same canonical form within the didactic elements of

their text. The-Hymn is a celebration of the

beauty and might of the-Aten and is demonstrated by its life-giving rays and flows

with phrases such as “push back the darkness … splendid, great, radiant … fill

every land with your beauty”.

Re-birth,

rewarding virtue, is a fundamental element of religion; Akhenaten didn’t have a

comprehensive solution for the after-life, darkness/night and what happened to

the-Aten during this time were unresolved

(Silverman,-Wegner-&-Wegner,-2006,-p.37) – we can deduce a naive fear of the night/unknown

during the-Aten’s absence (Schlögl,-2001,-p.158) and the absence of an

apotropaicbalance to the confident

nature of daytime. There was significant emphasis on recreation and re-birth

with the visible emergence of the sun each day in the eastern horizon being an

obvious demonstration of the-Aten’s daily re-generation. Atenism was a cosmic

doctrine and as such encompassed the “visible and perceived world” – Silverman,-Wegner-&-Wegner stress that the doctrine concentrated on

positive (not pessimistic) and animate elements (not inanimate), and day (not

night). Death was not a transition into the after-life but was more of a

“sleep” (Silverman,-Wegner-&-Wegner,-2006,-p.39) and

the new-day brought recreation (Aldred,-1971,-p.41) – the transition into the after-life (where a

person confirmed their worthiness) was absent and not replaced. The comforting

spells to confound the dangers of the underworld, shabti to perform menial

labour, and extensive funerary text were all lost – something that must have made

adoption of the-Aten difficult outside of Akhetaten’s closed-circle of

courtiers. Silverman,-Wegner-&-Wegner

(2006,-p.41) say that the people’s awareness

of Akhetaten’s human weakness became clear when one of his daughter’s (possibly

Meketaten) died – this is a somewhat bold statement and I feel that Akhetaten’s

isolation from all but a relatively small number of intimates would have

prevented most of the nation’s population from being aware of the ‘news’ from

the religious capital or to speculate on the King’s frailties.

The traditional

universe, or cosmos, was articulated by metaphysical creation-myths (Tobin,-2001,-p.362) and

different aspects of the creation-myths evolved (such as the

Heliopolitan-cosmology); there was a widespread understanding of the creation

(Wilkinson,-2000,-p.76).

Because the-Aten was ‘the one and only god’ there was a diminished requirement

for complex mythical concepts (Schlögl,-2001,-p.157) – Assmann (1995,-p.158) put it well saying “primeval origins are of

no importance in Amarna religion”. Tobin(2001,-p.469) explains that Atum emerged from

the primeval waters, like the rising-sun, who took the form of the creator

sun-god Re-Atum. Pyramid text 1248 describes Atum masturbating to create the

twins Shu and Tefnut - although Spell-76 of

the Coffin Text replaced masturbation with spitting. The-Aten’s early didactic

name included ‘Shu who is the–Aten’ (Shu was

replaced by Re from Akhenaten’s 9th-year

(Watterson,-2002,-p.63),

which I perceive as an example of the evolution of Akhenaten’s doctrine during

his reign) and Akhenaten and Nefertiti are depicted as the twin deities – and

therefore as the children of the-Aten.

The concept of Ma’at

(the harmony,

balance, and equilibrium of the entire cosmos which was traditionally embodied

within the Goddess Ma’at including Truth, Justice and Morality (Hart,-2001,-p.116)) was

preserved by the King, who was formally the high-priest of all Temples (Oaks,-2003,-p.154), an

his delegates. The-King was the guarantor of

the universe’s balance (Sauneron,-2000,-p.29) and

We can summarize the doctrine of the-Aten, as

defined by Akhenaten, as a solar monotheism where the sun-disk - as a

representation of the-Aten - was worshiped as the sole non-corporealdeity. The doctrine, which

was known exclusively to Akhenaten, evolved around light and Akhenaten (Schlögl,-2001,-p.158)

– Nefertiti played a secondary, but not subordinate, role within the triad of

Akhenaten, Nefertiti and the-Aten. So Akhenaten’s role was hugely significant

and, as Baines (2004,-p.281) wrote, he bore

the sole responsibility for all elements of life and beyond.

After

Akhenaten’s reign

The end of Akhenaten’s reign is as controversial as its beginning. Allen

(2007,-p.5) suggests that Akhenaten’s fourth daughter

Neferneferuaten was coregent for several years before being briefly succeeded

by Smenkhkare. However, the evidence is thinly circumstantial and I concur with

Dodson’s (2002,-p.279) that

ephemeral Smenkhkare succeeded Akhenaten and one of his epithets was Neferneferuaten.

Tutankhaten (‘Perfect is the Life of the-Aten’ (Silverman,-Wegner-&-Wegner,-2006,-p.7))

succeeded Smenkhkare

– although Tutankhaten’s parentage is hotly debated there is consensus that he

was married to Ankhesenpaaten (Akhenaten and Nefertiti’s third daughter) and because

of his young age effective power lay in the hands of his eventual successor Ay.

In the early years of Tutankhaten’s reign; the royal-court returned to

Conclusion

The term ‘revolution’ has

been used widely to describe this period although I feel ‘evolution’ is a

significantly better description. This ‘evolution’ is contained within

an interlude of less than 30-years (Silverman,-Wegner-&-Wegner,-2006,-p.1) and is one of the most enigmatic periods of Egyptian history; it came

to an end after shinning brightly at Akhetaten only to be concealed from view

for millennia. Despite significant archaeological discoveries in the last

100-years and extensive scholastic research the knowledge of Amenhotep-IV’s reign and his monotheistic belief in the-Aten is

still limited; commonly agreed facts of its origins, course, aftermath, and much

of its rational remains highly controversial and speculative.

Many theories have been proposed on Akhenaten’s

physical characteristics; in my opinion the most compelling offered (Reeve,-2005,-p.150/152) is

that Akhenaten suffered from Marfan’s Syndrome and was probably blind or very

visually impaired. Although this may explain his focus on the heat of the-Aten

it is irrelevant in determining Akhenaten’s doctrine or motivations.

Overall, I concur with Murnane (Allen,-2007,-p.1) that

fact should be valued over theory and a perfusion of highly theoretical

solutions to this enigmatic span-of-time we must strive to preserve an open

mind and to use evidence over conjecture to grasp its complexities.