The Cistercian Abbey of Basingwerk, Flintshire, Wales, was founded around 1131, although the exact date cannot be confirmed. It was established by Ranulf de Gernon, earl of Chester (1129-1153) and was at first a house of the Savigniac Order in Normandy. When all the Savigniac houses were absorbed by the Cistercians in 1147, Basingwerk became Cistercian. Grants of land and property came from both the Welsh princes and the English nobility. Edward I made it his headquarters while he was building Flint castle in 1277 (during his conquest of Wales), and in return for the abbey’s loyalty he granted the monks various privileges. It seems that Basingwerk’s sympathies lay with the English and the abbey provided a chaplain for Flint Castle. Basingwerk apparently suffered little during the Welsh wars although the abbey still received £100 compensation from Edward I for any damage inflicted upon its property.

The monastery was for an abbot and twelve monks, with a number of lay-brothers until the 14th century. In 1535, Basingwerk’s annual income was assessed at £150, at which time there were probably no more than two or three monks at the house. The house thus fell under the first phase of the Dissolution when all houses under the value of £200 were to be surrendered. Today only a little of the twelfth-century walling apparently survives around the cloister and in the east range, although the area has been fully excavated and the precinct outlines are clearly visible on the turf. Much of the fabric visible today, including the church, dates from the early thirteenth century, when the buildings were generally refurbished and extended. More important is the literary legacy of the abbey. The Book of Aneirin, one of the Four Ancient Books of Wales, transcribed in the second half of the thirteenth century, has been ascribed to Basingwerk Abbey. Basingwerk is also thought to have contributed to one of the greatest surviving medieval monastic Welsh annals: the Brut y Tywysogyon of the Chronicle of the Princes.

Virtually nothing is known of the abbey other than of the church, its surrounding buildings and the abbey pond. One evaluation in 1994, 83m south of the church, and around 35m south of the known claustral buildings purportedly revealed no medieval activity, but it has proved impossible to locate a copy of the report on the work. Geophysical survey on behalf of Cadw two years previously in 1992 revealed a little sub-surface detail of the south range, traces of a building, incomplete, to the east of the east range, and arguably a length of the precinct wall immediately to the west of the church. However, this runs very close to the west end of the church and also has a range of anomalies up against it which adopt an entirely different alignment to the known structures of the abbey, so it is quite possible that these are wholly unrelated to the medieval establishment. There is no evidence at all for the precinct boundary. Wood’s map of Holywell in the 1830s shows the open space around Basingwerk stretching further south than today, and interrupted only by the introduction of the tan yard and its enclosure. The nearby church of Holywell and the shrine chapel of St Winifred’s had been in the possession of the community of St Werburgh’s at Chester since the late 11th century, but were granted to Basingwerk by Daffydd ap Llywelyn in 1240 and this would have brought additional wealth to the abbey. Gresham has argued that it would also have become an important burying place for the uchelwyr of Tegeingl. It was dissolved in 1536. Massive industrial development of the Greenfield Valley in the 19th century has left the abbey ruins in a green pocket surrounding by industrial complexes, railway lines and housing. The Mills: The mill recorded close to the abbey at Basingwerk and within the curtilage of Abbey Farm is a post-medieval structure, and in the 19th century was referred to as Abbey Mills (Copper) by the Ordnance Survey. There is nothing to suggest that it occupies the site of a medieval predecessor, and indeed this looks to be an unlikely given the plateau-like location. Williams (1990, 38) records the existence of two water mills in 1240, apparently near the abbey gate, and known as the ‘upper’ and ‘nether’ corn mills; the former he equated with a mill site at SJ 186783, but again there is nothing obvious to corroborate the assertion. There were also two fulling mills known as the ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ walk-mills. To the north of the abbey church was a reservoir which previously seems to have been the site of the abbey pool or fishpond. Late 19th-century Ordnance Survey mapping termed it the ‘abbey pond’, though it was suspiciously rectangular in its depiction at that time. More helpful is Wood’s 1833 map which demonstrates that the pool was a more irregular and elongated body of water that extended further south-eastwards, probably give the impression that the pond also extended further to the north-west, but the natural topography belies this. The abbey pool is now a carpark. The abbey lay close to quarries of fine-grained sandstone, which would have been used for sepulchral slabs, and probably other purposes. The Setting Farm buildings lie to the south and south-west and are now used by the Green Valley Trust as a show farm. Stone-built for the most part these blend in with the abbey ruins.

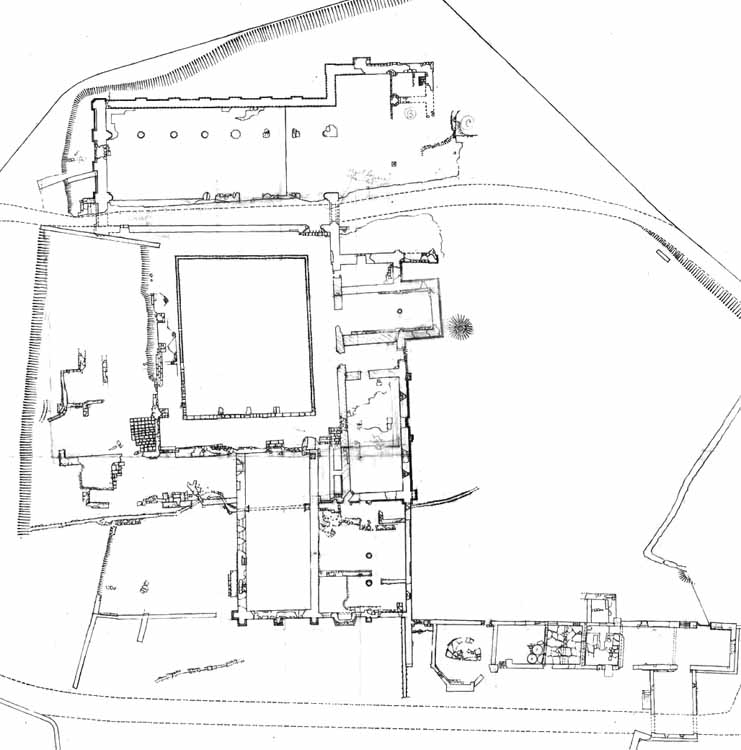

Plan made from a survey in October 1926 by the Office of Public Works:

Sources:

http://cistercians.shef.ac.uk/abbeys/basingwerk.php

Silvester, R, Hankinson, R, Owen, W and Jones W. 2011. Medieval and Early Post-Medieval Monastic and Ecclesiastical Sites in East and North-East Wales. Welshpool: The Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust.