The Cistercian Abbey at Furness, Cumbria, England,

was founded in 1124 by Stephen, then count of Mortain and lord of

Lancaster, and later king of England (1135-54). The original site

was at Tulketh near Preston in Lancashire. Three years later the

house was moved to a more suitable site on the Furness peninsula.

Furness was part of the Savigniac congregation and therefore

objected strongly to the union of Savigny and Citeaux. However their

protests were to no avail and Furness was absorbed into the

Cistercian Order in 1147 along with all the other Savigniac houses.

The abbey, under the special protection of the Crown, developed

rapidly and soon became almost as powerful as Fountains and for some

time years the abbey remained the only religious house

north of the Mersey and west of the Pennine Chain.

The abbey’s

endowments were considerable; it owned lands as far away as Ireland and

Yorkshire, and throughout the Middle Ages Furness and Fountains were

frequently to dispute landholdings in Cumbria. The rights and privileges

of Furness Abbey were confirmed and extended by every king from Henry I

to Henry IV, and in 1134 King Olaf of the Isle of Man, granted Furness

land for the foundation of a daughter-house and the right to elect the

bishop of the Isle of Man. The abbey of Furness achieved some feudal

independence over its lands in the north of England and the abbot’s

relations with Scotland were much like those of a border baron; only the

King of England could stand in the way of Furness’s sphere of influence.

The abbot was also an important person at the king’s court. When the

king came north the abbot collected subsidies, assisted the royal

officers and judges and acted as arbitrator. Furness' proximity to the

Scottish border meant that the abbey was embroiled in the conflict

between Scotland and England during the reign of King Stephen (1135-54).

Like so many other northern monasteries the house inevitably suffered

from raids at the hands of the Scots.

The ascendancy that the abbey achieved over its lands in the north

meant that the abbot often became involved in local disputes. For

example, in 1357 Thomas of Bordsey seized the bailiff whilst he was on

his duties and beat him. Following the attack, the bailiff went with a

company, including Abbot Alexander, to avenge the insult. Thomas was

duly captured and taken to jail.(6) By Henry VII’s reign it appears that

the abbot of Furness had take over the whole process of legal activity

in the area. The abbey was not only important in the north, it also sent

out colonies across England and Ireland: Calder in 1135 (which moved to

Byland), Swineshead in 1135, and Wyresdale c. 1196 (which moved to

Abington in Limerick, c.1205). Furness was wealthy: in the survey of 1535 the net annual income

was valued at £805 which made it the second richest Cistercian house in

England, after Fountains. As such it should not have been dissolved

until 1538/9 when the larger monasteries were forced to surrender.

However, the involvement of some of its monks in the uprising known as

in the Pilgrimage of Grace during the winter of 1536-7, and the fact

that Furness had openly questioned Henry VIII's declaration of supremacy

over the church, led to its closure in 1537. When Robert Radcliffe, a

close friend of the king, entered Lancashire to quell the disturbances

of 1536-7, his progress was marked by a series of executions. He

suggested that Furness surrender as a ‘voluntary discharge of

conscience’; the abbot followed his advice and this hastened the abbey’s

end. The house was dissolved in 1537 and demolition began almost

immediately. The property remained in private hands until 1923. When the buildings were

complete it is thought that they must have been among the finest series

of claustral ranges in England. Today, the remaining buildings include

the monk’s reredorter block, the guest-house, the abbot’s lodgings and

the monks' infirmary. Of particular interest is the sedilia in the

choir, which was skilfully carved and consists of four seats for the officiants and the double piscina required for the Mass. The refectory

and the lay- brothers’ building, on the other hand, are marked only by

their foundations. The infirmary demonstrates the wealth of Furness

better than any of the existing ruins.

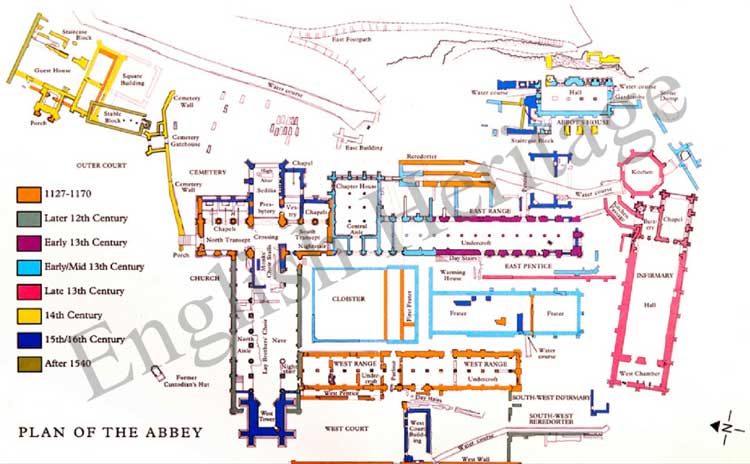

Plan (Leach):

Sources:

Leach, A. Furness Abbey.

http://www.furnessabbey.org.uk/page88.html (accessed 12-Jul-2013).

Robinson, D. 1998. The Cistercian Abbeys of Britain, London: B. T. Batsford.

University of Sheffield -

The Cistercians in

Yorkshire Project

Wilson, L. 1998. Furness Abbey (2009 edition), London: English Heritage.