Cistercian Abbey at Tintern, Gwent

Cistercian Abbey at Tintern, Gwent

The Abbey was founded in 1131 by Walter Fitz Richard (d. 1138), the Anglo-Norman Lord of Chepstow, and a member of the powerful family of Clare. Walter of Clare was also related by marriage to Bishop William of Winchester, who had introduced the first colony of Cistercians to Waverley in 1128. Tintern was the first Cistercian house to be founded in Wales and the second in the British Isles after Waverley.

Tintern abbey, situated deep in the Wye valley, was colonised by monks from L’Aumone (Loir-et-Cher) in the diocese of Blois in France. L’Aumone was in turn a daughter house of Cīteaux, and Tintern was therefore linked as a granddaughter to the Burgundian mother house. The community grew quickly and by 1139, had sufficient numbers to send out a colony to Kingswood in Gloucestershire. During its early years the house was blessed with, Abbot Henry, a man of great spirituality. Henry, who presided over the community from 1148-1157, had spent his youth as a robber, apparently a lucrative profession, but later repented and took the Cistercian habit; by all accounts he became an intensely religious man. Abbot Henry is known to have visited both the Pope and St. Bernard. In 1189 William Marshal, earl of Pembroke, became lord of Chepstow and patron of Tintern. Earl William was also lord of Leinster in south-east Ireland and, during a storm at sea, he promised God that he would establish a new monastery on these lands if he was saved from shipwreck. Thus Tintern sent out her second and final colony to establish the abbey of Tintern Parva (Little Tintern) on William’s lands in Ireland (1201-1203).

The abbey buildings appear to have been intended for a fairly large

community: some twenty monks and perhaps fifty lay-brothers. The abbey seems

to have been reasonably endowed with lands and possessions on both sides of

the river Wye. By the late thirteenth century the monks at Tintern were

farming well over 3000 acres of arable land on the Welsh side of the Wye and

kept some 3264 sheep on their pasture lands. In 1245 the lordship of

Chepstow passed to the Bigod family. Roger Bigod III, Earl of Norfolk

(1270-1306), took a keen interest in the abbey. In 1301-2 he granted the

abbey his Norfolk manor of Acle. This proved to be a valuable asset to

Tintern and by the sixteenth century was accounting for a quarter of the

abbey’s income. Roger Bigod was remembered primarily as the builder of the

abbey church. The project, which had commenced in 1269, was finally

concluded under the patronage of Roger, c. 1301. So great was the generosity

of Roger Bigod that later observers considered him to be the founder of the

abbey. At the time of the Dissolution the monks were still distributing alms

to the poor five times a year for the repose of Roger’s soul. The abbey was

at its most prosperous at the turn of the fourteenth century but afterwards

made no significant additions to its property.

The abbey buildings appear to have been intended for a fairly large

community: some twenty monks and perhaps fifty lay-brothers. The abbey seems

to have been reasonably endowed with lands and possessions on both sides of

the river Wye. By the late thirteenth century the monks at Tintern were

farming well over 3000 acres of arable land on the Welsh side of the Wye and

kept some 3264 sheep on their pasture lands. In 1245 the lordship of

Chepstow passed to the Bigod family. Roger Bigod III, Earl of Norfolk

(1270-1306), took a keen interest in the abbey. In 1301-2 he granted the

abbey his Norfolk manor of Acle. This proved to be a valuable asset to

Tintern and by the sixteenth century was accounting for a quarter of the

abbey’s income. Roger Bigod was remembered primarily as the builder of the

abbey church. The project, which had commenced in 1269, was finally

concluded under the patronage of Roger, c. 1301. So great was the generosity

of Roger Bigod that later observers considered him to be the founder of the

abbey. At the time of the Dissolution the monks were still distributing alms

to the poor five times a year for the repose of Roger’s soul. The abbey was

at its most prosperous at the turn of the fourteenth century but afterwards

made no significant additions to its property.

Tintern was one of the few Welsh abbeys that managed to escape the suffering inflicted by the wars of Edward II. No doubt this was due to the fact that Tintern occupied a site that was more remote than its Welsh counterparts and was thus outside the area in which most of the fighting took place. Edward II was known to have stayed at the abbey for two nights in 1326 when he was fleeing from the invading army of Roger Mortimer, but otherwise Tintern’s history remains a quiet one. By the early fifteenth century the abbey was experiencing some financial difficulties as a result of the damaging effects of the uprising of Owain Glyndwr. The community found some cash relief from the offerings of pilgrims who travelled to the abbey. The abbey chapel contained a statue of St. Mary the Virgin which was thought to have possessed miraculous powers and it was said a great number of people journeyed to visit this sight.

In 1535 the net annual income of the abbey was valued at £192, which made Tintern the wealthiest abbey in Wales at this time. Even so, the abbey came under the first Act of Suppression (1536) which dissolved all houses under an annual income of £200. The house was surrendered in September 1536 and the site was granted to Henry Somerset, earl of Worcester (d. 1549), who was the current patron of the house. The earl stripped the buildings of their roofs for lead; at some point during the following century a number of the monastic buildings may have been converted into dwelling houses.

In 1901 the site was

recognised as a monument of national importance and the property was sold to

the Crown. A restoration programme was set in motion which was completed c.1928.

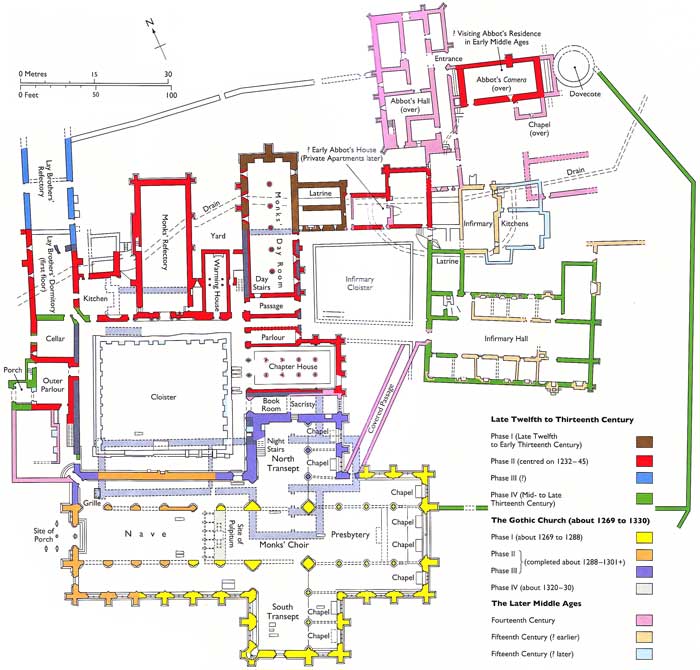

Today the site's gothic

church is almost complete, save the roof and the north aisle in the

nave. The excavated foundations of the communal guest hall and other inner

court structures can be seen to the west of the abbey church. The north-east

side of the abbey complex does not survive to any great height but shows the

lay out of the infirmary hall and the abbot’s lodgings.

The founding fathers of the Cistercian order had chosen to starve, rather than to accept gifts of manorialized or inhabited land. But such unencumbered holdings were hard to find on the twelfth-century Welsh border, even in the comparative remoteness of the Wye Valley. Walter of Clare was probably anxious to offload church property earlier grabbed by conquest, and included the manor of Porthcasseg with his original endowment to the Tintern monks. The community had little choice but to accept, as was true of his gift of Woolaston manor. They made efforts to carve consolidated granges within the bounds of each, but they were never entirely free of responsibility for serfs and tenants. The abbey was to hold a central court for all its tenants west of the Wye at Porthcasseg. Fines were levied, and manorial justice dispensed.

Much of Tintern's land was probably considered marginal in the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries. This was the way the Cistercians would have wanted it. From a very early date Tintern was busy extending and improving its agricultural holdings, cutting down woodland, and draining marsh on the Monmouthshire Levels. The monks also exchanged quite sizeable chunks of property in order to bring their estates closer together for more efficient management. The brothers also had a discerning eye for a balanced agricultural economy. Trelleck and Rogerstone were important arable granges, whereas at Moor there may have been a greater emphasis on pastoralism.

Source

University of Sheffield. Tintern Abbey.

The Cistercians in Yorkshire Project.

Robinson, D. 2011. Tintern Abbey. Cardiff: CADW.