King Men-Kau-Re and a Queen

King Men-Kau-Re and a Queen

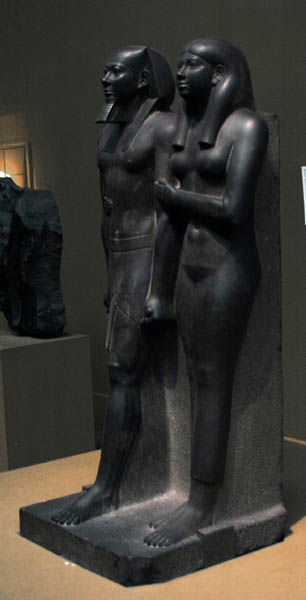

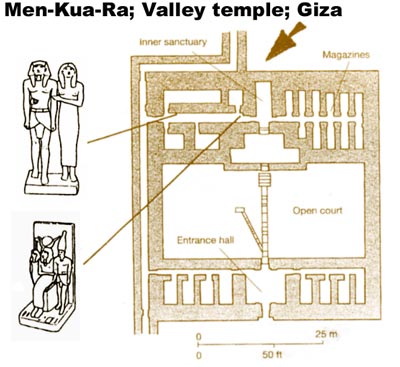

- At twilight on January 10, 1910, a young boy beckoned George Reisner to the Menkaure Valley

Temple. There, emerging from a robbers' pit into which they had been discarded were the tops of two heads, perfectly

preserved and nearly life-size. This was the modern world's first glimpse of one of humankind's artistic masterworks,

the statue of Menkaure and queen.

- The two figures stand side-by-side, gazing into eternity. He represents the epitome of kingship and the ideal human male form. She is the ideal female. He wears the Nemes on his head, a long artificial beard, and a wraparound kilt with central tab, all of which identify him as king. In his hands he clasps what may be abbreviated forms of the symbols of his office. His high cheekbones, bulbous nose, slight furrows running diagonally from his nose to the corners of his mouth, and lower lip thrust out in a slight pout, may be seen on her as well, although her face has a feminine fleshiness, which his lacks. Traces of red paint remain on his face and black paint on her wig.

His

broad shoulders, taut torso, and muscular arms and legs, all modelled with subtlety and restraint, convey a latent

strength. In contrast, her narrow shoulders and slim body, whose contours are apparent under her tight-fitting sheath

dress, represent the Egyptian ideal of femininity. As is standard for sculptures of Egyptian men, his left foot is

advanced, although all his weight remains on the right foot. Typically, Egyptian females are shown with both feet

together, but here, the left foot is shown slightly forward. Although they stand together sharing a common base and back

slab, and she embraces him, they remain aloof and share no emotion, either with the viewer or with each other.

His

broad shoulders, taut torso, and muscular arms and legs, all modelled with subtlety and restraint, convey a latent

strength. In contrast, her narrow shoulders and slim body, whose contours are apparent under her tight-fitting sheath

dress, represent the Egyptian ideal of femininity. As is standard for sculptures of Egyptian men, his left foot is

advanced, although all his weight remains on the right foot. Typically, Egyptian females are shown with both feet

together, but here, the left foot is shown slightly forward. Although they stand together sharing a common base and back

slab, and she embraces him, they remain aloof and share no emotion, either with the viewer or with each other.

Who is represented here? The base of the statue, which is usually inscribed with the names and titles of the subjects represented, was left unfinished and never received the final polish of most of the rest of the statue. Because it was found in Menkaure's Valley Temple and because it resembles other statues from the same find-spot bearing his name, there is no doubt that the male figure is King Menkaure. Reisner suggested that the woman was Queen Kamerernebty II, the only one of Menkaure's queens known by name. She, however, had only a mastaba tomb, while two unidentified queens of Menkaure had small pyramids. Others have suggested that she represents the goddess Hathor (see pp. 83-84), although she exhibits no divine attributes. Because later kings are often shown with their mothers, still other scholars have suggested that the woman by Menkaure's side may be his mother. However, in private sculpture when a man and woman are shown together and their relationship is indicated, they are most often husband and wife. Because private sculpture is modelled after royal examples, this suggests that she is indeed one of Menkaure's queens, but ultimately, the name of the woman represented in this splendid sculpture may never be known.