Reports of Lyon’s recovery of the stelae indicate that he is a Captain. He was gazetted Captain on 11-October-1892 and posted to Cairo as Assistant Quarter Master General on Lord Kitchener’s staff. When he recovered the stelae he was a Lieutenant (Internet_1). His duties allowed him ‘some flexibility’ and Frothingham (1894,p.260-261) reported that by 1894 Lyons had continued his work at Buhen.

1.4 Final steps in the decipherment of Hieroglyphs

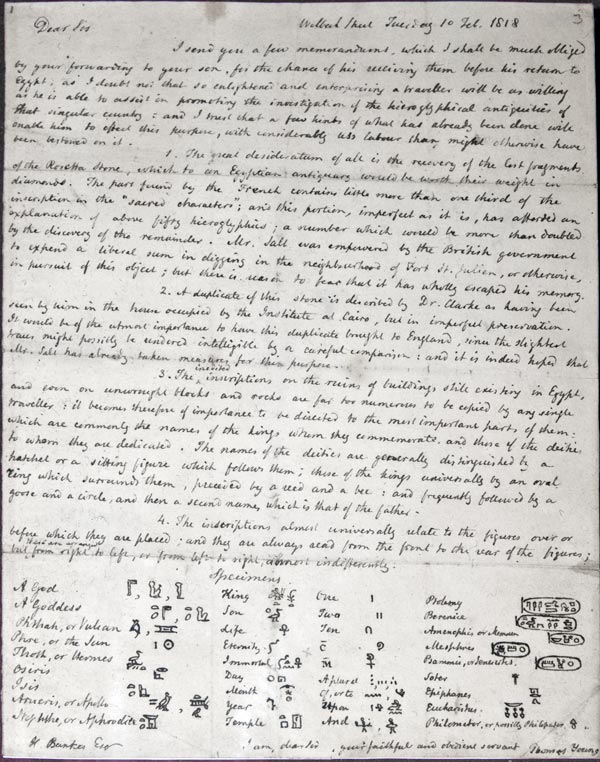

Young and Champollion were the principle protagonists in the race to decipher hieroglyphs; this dated to a period when England and France had recently been at War for many years (Parkinson, 1999, p.31).

1.4.1 Bankes’ Obelisk and Base

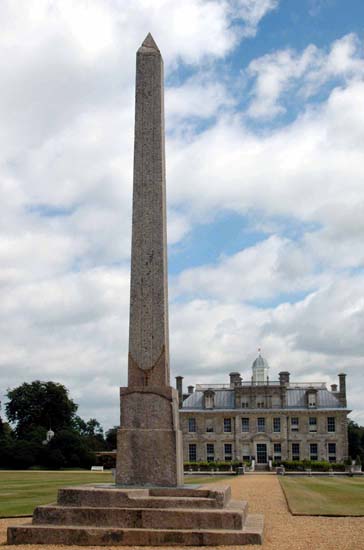

In 1821 Bankes’ Obelisk and also a red-granite base arrived in England having been discovered in 1815 and dispatched to his ancestral home at Kingston Hall, later Kingston Lacy (Parkinson, 1999, p.33). The base contained Greek inscriptions from PtolemyVIIIEuergetesII, who ruled Egypt between 170-116BCE (Shaw, 2002,p.482) and the priests of Isis on Philae in 124BCE. Bankes was able to determine that the cartouche on the base was that of Ptolemy’s queen CleopatraIII. The Obelisk and base contained useful additional information to the Rosetta Stone excavated from Fort St. Julian by Pierre François Xavier Bouchard in 1799 (Parkinson,1999,p.20); interestingly Young’s letter to Bankes says that a missing fragment of the Rosetta Stone would ‘be worth its weight in diamonds’. Ironically it was the Obelisk’s base that allowed Champollion to make his first major breakthrough (Champollion, 2001, p.130). In 1821 Bankes (Hooker, 2004, p.126) had a lithograph made of both the Greek and hieroglyphic texts and noted that the cartouches from the base and the Rosetta Stone were identical – Bankes also included his determination of the names of Ptolemy and Cleopatra. When Champollion received a copy it ‘turned bewildering investigation into brilliant and continuous decipherment’ (Hooker, 2004, p.126).

1.4.2 Bankes and Huyot at Abu Simbel

Bankes cleared some of the sand from RamessesII’s temple at Abu Simbel; this revealed many hieroglyphic texts which Bankes correctly determined to name RamessesII (Usick, 2002, p.119) but it also revealed a Greek inscription on one of the colossus’ legs naming Ramesses [Psammetichus] (James, 1997, p.93). Jean-Nicolas Huyot was at Abu Simbel with the Bankes party and he also recorded the text which contained the nomen of Ramesses and Thutmosis within cartouches (Parkinson, 1999, p.35). By-chance Huyot had been a member of the 1817 Cléopâtra expedition under Auguste de Forbin which had also included Linant de Bellefonds (member of Bankes’ party).

1.4.3 Champollion ‘wins the race’

Champollion had asked Huyot to copy texts whilst in Egypt (Usick, 2002, p.79); Huyot sent these texts to Champollion who, on the very day he received them (Saturday 14-September-1822), rushed to his brother, declaring ‘je tiens l’affaire’ before collapsing for 5 days (Adkins/Adkins, 2002, p.181). The direct result was that Champollion ‘won’ the race when, 13-days after collapsing, he read, with Young in the audience, his Lettre à M. Dacier at the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres in Paris on Friday 27-Spetember-1822 (Parkinson, 1999, p.35).

Young, Champollion, and Bankes were fated to be entwined in the deciphering of hieroglyphs and I agree with Daniels who wrote (Parkinson, 1999, p.40) that ‘decipherment has to stand or fall as a whole’ and I agree with Parkinson’s opinion that Young revealed part of the key to the alphabet but Champollion ‘unlocked the entire language’. Young’s work, assisted by Bankes epigraphic drawings and research, was carefully acknowledged by Champollion in 1824 when he said ‘I recognise that [Young] was the first to publish some correct distinctions concerning the general nature of these writings…’

2 The Stelae

2.1 The Temple and the Central-Sanctuary

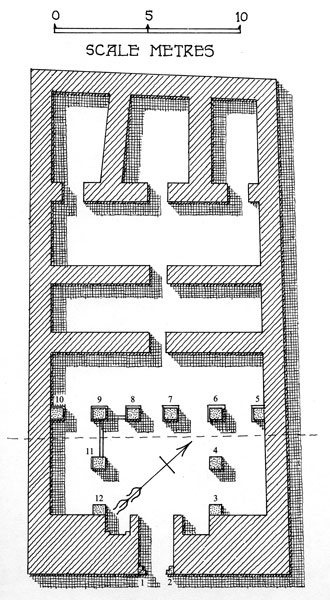

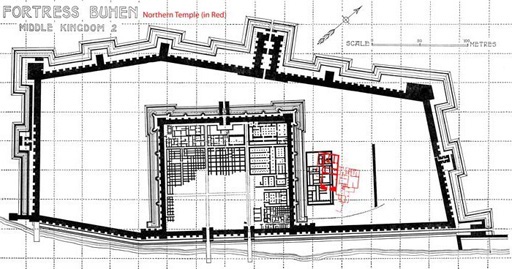

The University of Pennsylvania excavation by Randall-MacIver and Woolley (1909-1910) established that the temple (Figure-11.a) was re-built for Amenhotep-II (ruled 1427-1400-BCE (Shaw, 2002, p.482)) and it replaced a temple built for Ahmose (ruled 1550-1525-BCE (Shaw, 2002, p.482)) and both Ahmose and Amenhotep included dedications to Horus of Buhen. Porter/Moss (1995, p.129) confirm that the temple was dedicated to Isis although it was notable for its ‘poverty and insignificance’ (Randal-MacIver/Woolley, 1911a, p.89) and its irregular rooms (Figure-5.b).

2.1.1 North Temple of Ahmose

Kamose, Ahmose’s uncle (Dodson/Hilton, 2004, p.124) who died of combat wounds after a short reign, re-captured Buhen from the ruler of Kush by his 3rd regnal-year (Shaw, 2002, p.207). I suggest that Ahmose’s temple may have been built quickly during the turbulent beginning of the 18th-Dynasty, while Ahmose was battling Avaris and possibly before he vanquished Nubia (Edwards/Gadd/Hammond/Sollberger, 1973, p.296-298).

2.1.2 North Temple of Amenhotep II

Ahmose’s temple was replaced by that of AmenhotepII; the last King with an inscription recorded within the temple is RamessesXI of the 19th-Dynasty (Porter/Moss, 1995, p.130) [Carian inscriptions were not found (Masson, 1978)].

Usick (1999, p.334) quotes Bankes who realized that General Montuhotep’s stela had been ‘placed there subsequently’ because the rear-wall on which it leaned was smooth and plastered. I disagree with Caminos (1974, p.106) suggestion that the stelae were placed in Amenhotep’s temple to add ‘lustre’ and I consider that they were placed within the central-sanctuary of the North Temple for their symbolism which emphasised the parallels between Ahmose and Amenhotep’s similar victories and, by-extension, reigns.

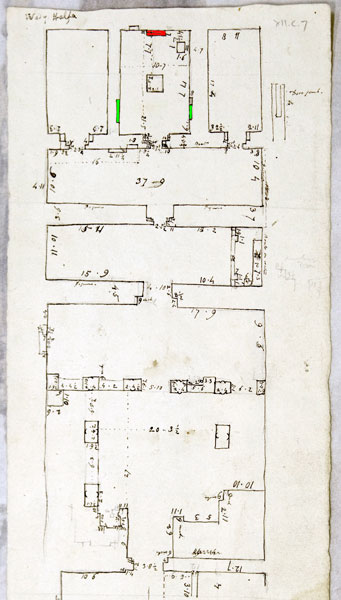

The central-sanctuary, as measured by Bankes, is 17’7” long and 10’7” wide (Figure-5.a) and Bankes described it as having brilliant colouring (Bankes,1923,p.121). Bankes’ plan did not record that the rear-wall was narrower than the entrance-wall and that the room was somewhat irregular, as Emery’s plan demonstrates (Figure-5.b). Snape (2007,p.76) calculated that the floor-level of the inner-sanctuary was only marginally higher, perhaps 10-15-cm, than the courtyard floor and Bankes (1923,p.121) wrote in 1819 that the other chambers were probably ‘loftier’. This conforms to the usual design of Temples where the most sacred room had the lowest-ceiling and the highest-floor (Bell,2005,p.133).

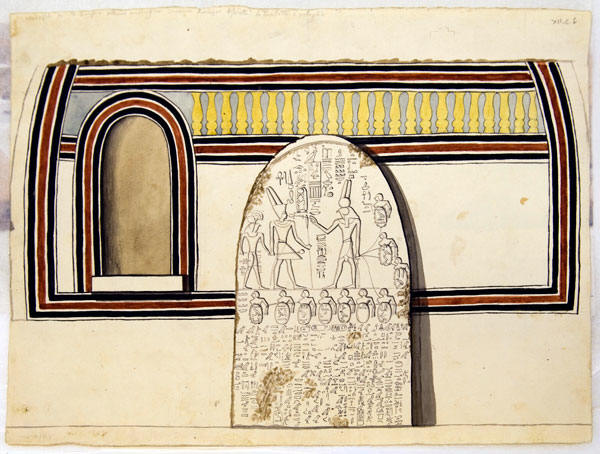

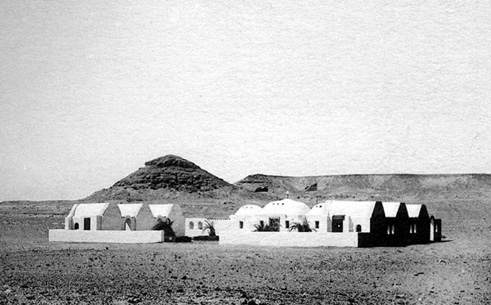

The rear-wall, painted by Ricci (Figure-6.c), is depicted as being decorated with a red and black border and a yellow and grey Kheker-Frieze [decorative element representing upright bundles of reeds (Arnold,2003,p.122)] and having a curved or arched wall (Usick,1998b,p.485-487). This would suggest the each of the roofs of the inner-courts may have been covered by an arched roof which was individually constructed to span each chamber. The Northern temple is predominantly constructed from mud-brick (Randal-MacIver/Woolley,1911a,p.105); the inner-courts lack stone pillars which are commonly found in Egyptian temples to support a conventional flat roof (Arnold,2003,p.204). This may be unusual in Egyptian temples but this building technique is common to many Nubia buildings (Randal-MacIver/Woolley,1911a,p.84) and Figure-10 shows a contemporary example.

2.2 Stela of General Montuhotep

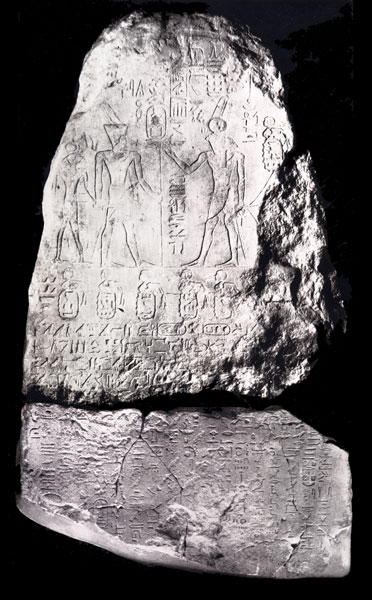

The stela (Figure-6.a and Figure-6.d) celebrates the General’s victories over ten locations in Nubia during the 18th regnal-year of the reign of SenusretI (ruled 1956-1911BCE (Shaw, 2002, p.480)). It was found by Bankes (Usick, 1998b, p.484-485) leaning against the rear-wall, see Figure-5.a highlighted in red [the empty round-topped niche is smaller than General Montuhotep’s stela].

2.2.1 Description of the Stela

The sandstone stela is held by the Museo Egizio di Firenze and is in two distinct fragments (inventory numbers 2540a and 2540b); 2540a was recovered by the Franco-Tuscan expedition and 2540b by Captain Lyons (Bosticco, 1959, p.31). The fragments are approximately 1.05-meters wide and 1.92-meters tall.

The stela has been described in detail in Bosticco (1959, p.31-33), Breasted (1906, 247-250), and Smith (1976, p.39-41); in summary:

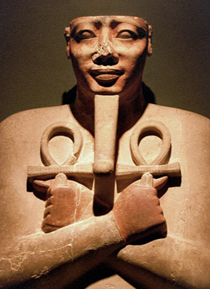

SenusretI (Figure-13), protected by Horus-Behdet, presents to Montu the captured locations within TA Sty [Nubia (Internet_2)]. mnTw [deity Montu (Wilkinson, 2003, p.203-204)] was a falcon-headed war-god venerated in Thebes and who was closely associated with the Middle-Kingdom; the Nomen shared by 11th-Dynasty Kings’ was Montuhotep [Montu-is-Content (Internet_2)]. mnTwholds four ropes which are joined to ten captured and restrained figures with fortified ovals; each oval contains the name of a defeated foreign-land. Montuhotep recorded his titles and honours within the Egyptian nobility, his military titles, and extolled that he annihilated the peoples of this region on the lower section of the stela which has been badly damaged.

2.2.2 Ten locations in Nubia

Smith (1976, p.39) explains the importance of Ricci’s drawing in helping understand the names of the localities. Smith, Breasted, and Bosticco differ slightly in their interpretation of the locations and only Smith had viewed Ricci’s 1819 drawing:

|

Breasted |

Smith |

Suggested Location |

|

kAs |

kAs |

Kush |

|

y |

HAw..(?) |

|

|

prww |

yA |

Yam |

|

ymAw |

imA or iAm |

Iam |

|

X |

..? |

|

|

wAw |

SAw(?) |

|

|

yxrkyn |

Ixrqyn |

|

|

SAa.t |

SAat |

Sai Island |

|

HSAy |

XsAi |

|

|

Smyk |

Smyk |

|

2.2.2.1 kAs O’Connor (1986, p.42) confirms that kAs [Kush] is the first location recorded on the stela and O’Connor (1978, p.64) also wrote that this is the earliest mention of kAs. The location of Kush is still debated; O’Connor (1986, p.39) and Tyson-Smith (2003, p.75) agree that Kush, as defined by Egypt, was a region stretching between the 2nd and 4th-cataracts and is not a locality as the stela implies. 2.2.2.2 yA and imA Adams (1977, p.158 and p.186) thought that yA was not recorded after the 6th-Dyansty when King Merenre sent Iri and his son Harkhuf to Yam ‘to explore the way there’ and where Harkhuf later met the Chief of Yam (Goedicke, 1981, p.2 and p.9) but Montuhotep’s stela disproves this. Smith (1976, p.39) and Trigger (1976, p.54-56) identify imA with a location mentioned in the 6th-Dynasty by Weni and visited by Harkhuf. However other sources, such as Goedicke (1981, p.1-2 and p.7-8) and Lichtheim (1975, p.19) refer to visiting yA, not imA. Ricci’s painting (Figure-6.a) clearly uses different hieroglyphs for the locations of yA and imA. Montuhotep may have known these to be different locations or alternatively that yA was an archaic toponym and the stela includes this as a location, and possibly others, to stress the importance of his achievements. 2.2.2.3 SAat SAat can be firmly located as Sai Island (ancient name of Sha’t) and the Kingdom of SAat (Trigger/Kemp/O’Connor/Lloyd, 2001, p.134) and the Temple of Kumma (Caminos, 1998, p.3 and p.51) has five inscriptions of HD nfr n SAat [fine white stone of Sha’t] on its door jambs. 2.2.2.4 Sequence of the locations The stela should not be confused with a geographic map, it is unlikely that locations only represent distinct tribal-lands, and I concur with Kemp (2001, p.134) that kAs is both a specific location and a term associated with a region. The locations may imply a north-south sequence, Posener (O’Connor, 1986, p.39) believes that this is supported by Execration Texts [such as the cache excavated at Mirgissa which included the chiefs from south of the 2nd and 3rd-Cataracts, Nubian desert regions and the Medjay people (Seidlmayer, 2001, p.308)] which list kAs before SAat, but an equally valid possibility is that the north-south sequence is determined by the four ropes binding the prisoners and that the first three locations are valid but the remaining seven might be read either right-to-left or left-to-right (making imA either the most southerly or northerly location).

2.2.3 General Montuhotep and his Army

Breasted (1906, p.249) and Bosticco (1959, p.31-33) wrote that Montuhotep’s inscription said:

2.2.3.1 18th Regnal-Year The stela refers to 18th regnal-year of SenusretI. Grajetzki (2006, p.33) argues that Amenemhat I (ruled 1985-1956-BCE (Shaw, 2002, p.480)) instigated a coregency during his 20th regnal-year with his son Senusret. The coregency of Amenemhat and Senusret is debated, primarily because stela CG20514 may be interpreted to record either a 10-year coregency or a 10-year period of time (Murnane, 2001, p.308). I concur with Grajetzki that it did exist in common with other 12th-Dynasty coregencies such as Senusret-I and Amenemhat-II and Amenemhat-II and Senusret-II. The regnal-years of Senusret and Amenemhat were counted independently – so Senusret’s 1st-year is also Amenemhat’s 20th-year and when General Montuhotep was campaigning in Nubia Senusret had only ruled independently for up-to 8-years. Coregencies provided a practical division-of-responsibilities and continuity between rulers. Lichtheim (1975, p.135-139) explained that the didactic ‘Instruction of King Amenemhat-I to his son Senusret [Sesostris]’ indicates that Amenemhat was assassinated and that Senusret was an experienced leader when he suddenly became king - both Montuhotep’s stela and the ‘Story of Sinuhe’ (Lichtheim, 1975, p.222-235) demonstrate this. Sinuhe explains the division of responsibilities within the coregency saying that Amenemhat ‘stayed in his palace’ and that Senusret was the ‘smiter of foreign lands’. At least one previous campaign into Nubia is recorded (Grajetzki, 2006, p.43) and although Montuhotep’s stela does not confirm that the King was present Breasted (1906, p.247) and Grajetzki (2006, p.42) agree that tomb inscriptions of Sarenput [Governor of Elephantine] and Amenemhat [Governor of Beni-Hassan] suggests that Senusret was personally present in Nubia during the campaign. 2.2.3.2 Secular Role Breasted (1906, p.249) and Bosticco (1959, p.32-33) listed Montuhotep impressive series of titles. Leprohon (1993, p.424) described some of his titles to be within the ‘Inner Palace’ indicating that they were some of the most senior roles within the King’s retinue. The titles included:

|

overseer-of-recruits (General) |

nfrw-imy-r-mSi |

|

overseer-of-the-army (General) |

imy-r-mSi |

Faulkner (1953, p.37) explains that in the 12th-Dynasty Nomarchs effectively retained private or local armies (Figures-12.a and 12.b) but the King would draw on these trained troops when required. Faulkner added that the King would also have maintained a standing national army to enforce the ‘King’s peace’ and this force was recruited by conscription and could be deployed in military or labour duties (such as mining-expeditions or building-projects). For example Sadek (1980, p.1 and p.17-18) recorded an expedition during Senusret’s 17th regnal-year to mine Amethyst in Wadi Huda [20-miles south-east of Aswan]. The expedition, as well as specialists, contained 1,000 xpSw [possibly conscripted recruits for manual activities] from the Southern City [Thebes], 200 aHAwty from Elephantine, and 100 aHAwty from Kom Ombo (Faulkner, 1953, p.40). Faulkner defined aHAwty as warrior or professional soldier but Stefanovié (2007, p.123) wrote that although aHAwty means soldier or warrior it ranks lower than anx [the ordinary soldier] and that aHAwty were recruited from different Nomes; the Semna Dispatches (Smither, 1945, p.6-10) indicate that their function included controlling and monitoring the movements of non-Egyptians within Lower-Nubia. Fields (2007, p.8) writes that Egyptian soldiers spent very little time on military operations and that they were primarily used as an unskilled labour force. The Middle-Kingdom army was comprised entirely of infantry and included archers, slingers, spearmen, and axmen who had minimal bodily defence except cow-hide shields (Adams, 1977, p.182). Recruits were unlikely to be content with being taken from their homes and families to distant and hostile lands and Simpson (1978, p.346) in ‘Hardships of the Soldier’s Life’ recorded a Ramesside didactic text to say:

A solider is a much castigated one

He is beaten like papyrus and wounded

His carries his rations like the load of an Ass

He returns to Egypt like a worm devoured stick

The most senior military title in the 12th-Dynasty (Faulkner, 1953, p.37) was imy-r-mSi-wr [generalissimo, but not necessarily a field-commander] and the person holding this title was associated with the King’s Army and not a local force. If the King or imy-r-mSi-wr were not present a military or labour force was commanded by an imy-r-mSi [general] such as Montuhotep. Faulkner (1953, p.38) observed that during a single mining expedition to Sinai there were 10 individuals described as imy-r-mSi. The textual evidence does indicate whether Montuhotep was imy-r-mSi in the King’s army, whether he was commanding troops from dp that constituted his private army, or if he was the King’s representative with field-command of a number of imy-r-mSi. It is highly unlikely that a Nome in Lower Egypt would dispatch troops to Nubia without support from other Nomes; so I suggest that this was a combined force of local and national troops possibly under the sole command of Montuhotep. 2.2.3.4 Transport and Logistics Montuhotep does not mention shipping but O’Connor (1986, p.49) proposes that during this campaign an Egyptian war-fleet broke through the 2nd and 3rd-Cataracts to the Dongola Reach ‘inflicting considerable damage on the riverine communities’. The logistical challenges of moving an army from different locations within Egypt to the 2nd-Cataract, and possibly beyond, suggests that a large number of ships would have been employed to transport the troops and their supplies. Nicoll (2004, p.249-250) explained that in 1885-CE, during the Mahdist War, an army sailed up-stream through the 2nd-Cataract using 6,000 local labourers, specialized boats and watermen, and steal hawsers. For an Egyptian army to navigate the cataract without exposing their troops and supplies to significant risk would have been a challenge. I suggest that shipping and supplies may have been moved over-land to avoid the risk of loss. SenusretI, during his 24th regnal-year, dispatched Antefoqer and Ameny to ‘the mine in Punt’ (Fabre, 2005, p.41 and p.82-83) which involved a voyage on the wAD-wr[Great Green (Internal_2)]. Ships were built at Getbu [Koptos (Baines/Málek, 1980, p.111)] and transported across the dessert to the Red Sea before being re-constructed. This demonstrates that ships were successfully moved over long distances and taking a land-route to avoid the cataract would have been very possible. Montuhotep did not record the size of his army or the duration of the campaign. To invade such a large region would have required a force of some size not only of soldiers but also support personnel. The region was thought to be lightly-populated (O’Connor, 1993, p.3) and I suggest that Montuhotep did not require an army of tens-of-thousands. Montuhotep might have commanded a force of between 2,000 and 4,000 troops and for combat-operations using ships a smaller number would have been deployed, possibly as few as 2,000 combat-troops, over a 90-day campaign. Kemp (2006, p.175 and 177-178) used wooden tallies from the Middle-Kingdom fortress at Uronarti to determine that each solider was allocated two-thirds of a Hekat (a measure of volume equal to 4.78 litres [0.00478 of a cubic meter]) of barley and one Hekat of wheat every ten-days. This was not the only rations that a soldier was provided but it can be used to estimate the amount of grain required to support a force of 2,000 combat-troops for a 90-day campaign:|

For each Soldier |

|

|

Wheat @ 3.75 Kg/Hekat * 1.00 per10-days |

3.75 Kg |

|

Barley @ 3.37 Kg/Hekat * 0.66 per10-days |

2.25 Kg |

|

10-days ration for each soldier |

6.00 Kg |

|

Multiply by nine (90-day campaign) |

54.00 Kg |

|

|

|

|

For a combat-force of 2,000 soldiers |

|

|

Multiply by 2,000 soldiers (2,000 * 54 Kg) |

108 Tons |

Their life is finished

Slain …

Fire in their tents

Her grain cast into the Nile

A similar inscription (Parkinson, 2004, p.95-96) was discovered at el-Girgawi (in the vicinity of Korosko (Baines/Málek, 1980, p.179) approximately 100-miles down-stream of Buhen) amongst over seventy crude graffiti dated to Amenemhat and SenusretI. An inscription by ‘Intefiqer, who was called Gem’, says:I am… from Luxor

I went upstream slaughtering Nubians

I came back downstream stripping crops

Cutting down the rest of their trees

Put fire to their homes

I consider that Montuhotep’s inscription, supported by corroborating information from Intefiqer, is not merely bombastic prose but a vivid description of the punitive nature the campaign and the inscription implies that the local population was purged from this region, their dwellings destroyed, and their food and future seed crops, were eradicated. We might judge this to be ethnic cleansing of the region. The purging of the indigenous population was not totally successful. During SenusretIII’s 16th regnal-year stelae were erected at Semna and Uronarti which echo previous claims and indicate that the region was still populated (Parkinson, 2004, p.43-44):

2.2.4 General Montuhotep, Summary

General Montuhotep’s stela, although badly damaged, is a vital record of Egypt’s determination to control this region and to remove all resistance; it establishes actions, places, and people within a single historical context. Although Bankes expedition revealed this stela it was Champollion, with his ability to read the inscriptions, who recognized its importance as a record of events that happened nearly four millennia ago.

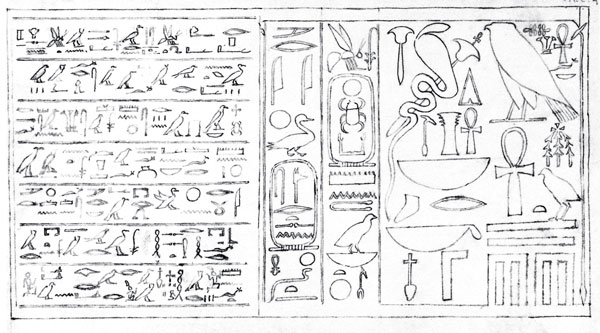

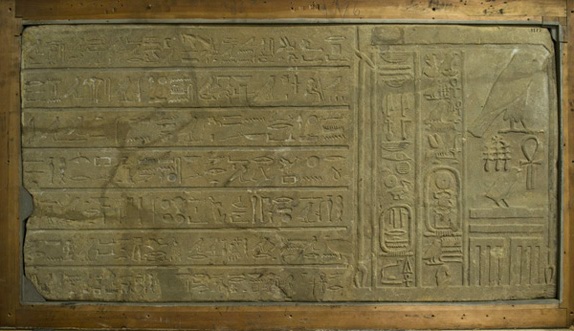

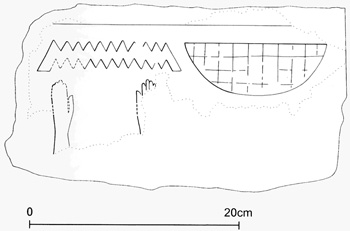

2.3 Two similar Stelae of General Dedu-Intef

The stelae (Figures 7a, 7.b, and 7.c) commemorate General Dedu-Intef and date to the reign of SenusretI. They were originally set into recesses in the left and right walls of the central-sanctuary (Figure-5 highlighted in green). They were discovered by Bankes (Usick, 1998b, p.484-485) in-situ and removed by Lyons from a ‘mass of broken and crumbled mud brick’ (Snape, 2007, p.76).

2.3.1 Description of Stela EA 1177

Stela EA 1177, inscribed into yellow sandstone, is held by the British Museum and was registered in 1894 (Smith, 1976, p.50). It is 116cm wide and 63cm tall (Figure 7.c). The inscription of the missing stela has been described in detail in Laming-Macadam (1946, p.60-61) and Smith (1976, p.50-52) compares both stelae.

2.3.1.1 Royal Titulary Smith (1976, p.50) observed that EA 1177 has more text than the missing stela. The Royal Titulary on the missing stela is 66cm wide with 50cm of text, EA 1177 has a narrower Titulary, 46cm, and 70cm of text. EA 1177 has proportionally more text and, therefore, more descriptive information. The hieroglyphs (Internet_2) represent the Horus name of SenusretI, Hr-anx-mswt [Horus, Living of births], Prenomen xpr-kA-ra [Ka of Re has come to life] and Nomen s-n-wsrt [Man of the Strong One]. Senusret is associated with wADyton the missing stela and mnTw(see2.2.1) on both stelae. wADyt is usually shown in the form of an erect Cobra and was the titulary deity of Lower Egypt (Wilkinson, 2003, p.226). 2.3.1.2 Dedu-Intef’s titles Laming-Macadam (1946, p.61) recorded Dedu-Intef’s titles, which are similar to Montuhotep’s, to include:

Prince

Governor

Treasurer

Sole Companion

Priest of the secrets which only one hears

2.3.1.3 Self-praise of Dedu-Intef Dedu-Intef included many bombastic self-praising phrases onto the stelae (Laming-Macadam, 1946, p.61):

Great in his office

Mighty in his dignity

Magistrate at the forefront of the people

Confidant of Horus Lord of the Palace

Trusted one of the king in quelling the rebellious

2.3.1.4 Military roles Dedu-Intef included three military roles within the stela (Laming-Macadam, 1946, p.61):|

imy-r-mSi-mnfAt |

overseer-of-shock-troops (Faulkner, 1953, p.38) |

|

imy-r-Hwnw-nfrw |

overseer-of-recruits (Faulkner, 1953, p.39) |

|

Each stela has a final imy-r followed by hieroglyphs with an unclear meaning; Smith (1976, p.51) offers that this could be overseer-of-plans but this is unsupported.

Faulkner (1953, p.40) also suggested that the title’s order determines their seniority therefore overseer-of-shock-troops is junior to overseer-of-recruits. |

|

2.3.2 General Dedu-Intef, Summary

General Dedu-Intef’s stelae contain autobiographical and self-praising information and are dated to Senusret-I and indicate Dedu-Intef’s military roles. However they contain very little information of historical interest and without their find-spot being known they would be historically insignificant.

2.4 Careers after the Nubian Campaign

After their victorious campaign in Nubia we might expect that these two individuals would re-appear within Egyptian History.

From Montuhotep’s stela we have an extensive list of his Secular and Military titles. The bottom left of the stela has an inscription suggesting that Montuhotep was the Son of Ahmu [sAamu (Smith, 1976, p.41)] but the stela is extensively damaged in this section and Ricci’s version also shows damage and the hieroglyphs are unclear (Figure-6.a and Figure-6.d); Smith must have relied on Ricci’s copy to determine the name of Ahmu.

From the Old-Kingdom the King’s tomb was surrounded by the tombs of his officials and relatives (Arnold, 2008, p.13, p.38-39). SenusretI was buried within a pyramid at Lisht-South which was completed by his 25th regnal-year close to the capital Amenemhat-Itj-Tawy. One Mastaba, located against the Enclosure-Wall of Senusret’s complex and excavated by the Metropolitan Museum in the 1990s, was that of Montuhotep; Arnold (2008, p.39) explained that Montuhotep ‘first appears’ in an inscription dating to Senusret’s 18th regnal-year but unfortunately he doesn’t explain whether this is related to the stela.

The extensive Tomb of Montuhotep contained titles including (Arnold, 2008, p.38-45):

Prince

Treasurer [Overseer-of-what-is-sealed (Arnold, 2008, Plate.70)]

Spokesman of every Pe and Dep

Royal Seal Bearer

Sole Companion

Vizier (?)

Mayor of the Pyramid City (possibly AmenemhatI)

Son of As-en-Ka

The titles within the Tomb of Montuhotep, which are significantly damaged, have a similarity to those inscribed on the stela plus additional ones which might be expected during a successful career; these included being granted additional responsibilities such as Mayor of the Pyramid City and possible Vizier.

The Tomb of Montuhotep does not contain any military titles.

Arnold (2008, p.41) records the owner to be the Son of As-en-Ka but the stela records that Montuhotep is possibly the Son of Ahmu. Arnold offers the possibility that the tomb’s inscription is incorrect (Figure-14) because only a that few ‘pieces of the inscriptions had been preserved’ and the name was possibly ///nb//n kA/// or ///s n kA n///(?). In a personal email to author Arnold confirmed that fragments of Montuhotep’s statues, recorded in Obsomer’s ‘Sesostris Ier’ (1995, p.22-27), suggest his mother’s name was As-en-Ka and that the tomb does not indicate the name.

Although the Tomb and stela may be for the same individual, on balance, there is insufficient evidence to demonstrate this.

3 Historical Context of the Stelae

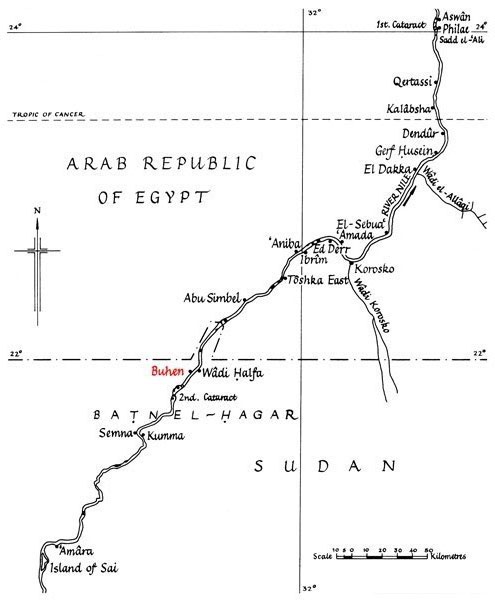

3.1.1 Nubia

By the Old-Kingdom Egyptians referred to the region between Aswan and the 2nd-Cataract as Wawat [wAwAt (Internet_2)]; modern-texts often refer to Wawat as Lower-Nubia - which is now submerged within Lake Nasser (Welsby, 1998, p.7). Morkot (2000, p.48) explains that during the 6th-Dynasty the Chiefs of Wawat, Irtjet, Yam, Satju, and Mejda were in Egypt’s service but over time these Tribes merged into a single entity under the Chief of Wawat. Tyson-Smith (2003, p.57) makes a good observation that Wawat is not a geographically location but the ethnic grouping of the Wawat peoples.

Batn el-Hagar [Belly of the Rock (Morkot, 2000, p.5)] is the Arabic name for the 2nd-Cataract. Tyson-Smith (2003, p.75-76) says that Batn el-Hagar [Hajar] was both the political and cultural boundary that demarked Egypt during the Middle-Kingdom and this formed a natural barrier and buffer-zone between Lower-Nubia and Upper-Nubia.

Upper-Nubia is the region up-stream of the 2nd-Cataract stretching to the 4th-Cataract (Morkot, 2000, p.5) and it was under the influence of the Kingdom of Kush [Kerma] (Tyson-Smith, 2003, p.76).

3.1.2 Lower-Nubia Terrain

Egypt and Nubia share the Nile but their geography is distinct. Egypt fringes the slow-moving Nile and man-made irrigation makes the broad floor-plains into fertile bands of land (Brooklyn Museum, 1978, p.17). Nubia is generally harsher and hyper-arid; arable land occurs in disconnected patches and often wind-blown sands or weather-smooth Granite Mountains extend directly to the Nile’s edge.

The geological composition of Nubia is complex; igneous and metamorphic rock from the Basement Complex has been uplifted and exposed in this area. The Nile has eroded the soft overlying Nubian sandstone and carved deep channels that expose the igneous rocks. Cataracts have been formed from where the Basement Complex, is exposed (Trigger/Kemp/O’Connor/Lloyd, 2001, p.40) and the Nile’s flow is separated by six cataracts (Stern/Abdelsalam, 1996, p.1696) which deter navigation forming rapids of fast-flowing water punctuated by outcrops of rock.

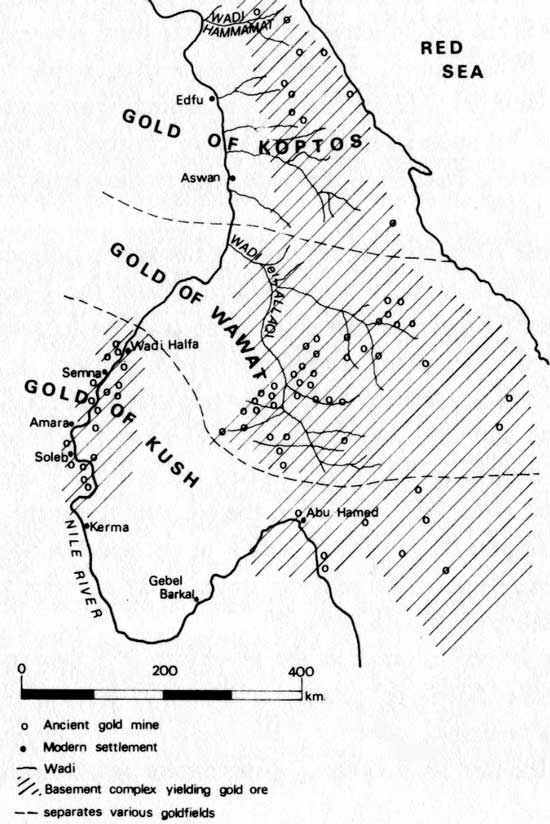

Figure-11.b shows the location of Wadi el-Allaqi and Figure-11.c shows the location of gold-mines. It is comprised of an extensive network of broad Wadi [dry riverbed] and joins the Nile at Kubban. From slag-heaps at Kubban Trigger/Kemp/O’Connor/Lloyd (2001, p.122) argue that the Wadi also contains Copper and they also presume that this was the main area of contact with the Medjay peoples.

3.1.4 Lower-Nubia Population

Trigger suggests that Lower-Nubia may have had a population of 17,000 people (Adams, 1977, p.159) and Tyson-Smith suggests 20,000 (2003, p.75). Morkot (2000, p.45) explained that surveys of Lower-Nubia indicate that the region was depopulated during the Old-Kingdom and by the Middle-Kingdom the region was thought to be lightly-populated; O’Connor (1993, p.3) says that there was a ‘ribbon’ of villages along the west-bank of the Nile, except within the Cataracts, and that nomadic pastoralists grazed areas along the Nile. Gohary (1998, p.7-8) adds that the region was populated by the C-Group culture which had slowly migrated into the area as Egypt’s involvement diminished during the First-Intermediate-Period. Edwards (2005, p.88) supports Morkot’s opinion adding that it is ‘difficult to identify any significant settlement’ and that repopulation of the region was a lengthy process. On balance I consider that Trigger and Tyson-Smith’s estimates are high for such a rugged and inhospitable environment and I suggest a more realistic population was 10,000 people including nomadic pastoralists.

3.2 The Middle-Kingdom, a Classical-Period

The Middle-Kingdom was viewed by the Egyptians, during the New-Kingdom and even the Late-Period, as being a time of “unprecedented wealth and stability" (Grajetzki, 2006, p.1) and where political stability was matched by a Classical-Period of Egyptian Arts, History, and Literature.

3.2.1 Chronology of the Middle-Kingdom

The division of the First-Intermediate-Period - which separates the Old-Kingdom and the Middle-Kingdom - is open to interpretation; I support Shaw and Grajetzki’s view that the First-Intermediate-Period was before-unification (9th, 10th, and the 1st-part of the 11th-Dynasty) and the Middle-Kingdom was after-unification (rulers from Montuhotep-II onwards):

|

First-Intermediate-Period

Before Unification |

9th and 10th-Dynasties(Herakleopolitan) |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

11th-Dynasty (Thebes only) |

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|||

|

Middle-Kingdom

Unified Egypt |

11th-Dynasty |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

12th-Dynasty |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.2.2 11th Dynasty, Unification

MontuhotepII ruled for 51-years and was respected by subsequent Kings as a unifier of Egypt and the Middle-Kingdom’s founder - a Classical-Period which spanned nearly 200-years. Montuhotep changed his titulary a number of times; finally to ‘he who united the two countries’ which suggests that Egypt was unified from his 39th regnal-year or 2016BCE (Grajetzki, 2006, p.19).

Grajetzki (2006, p.20) writes that by the end of Montuhotep’s reign Lower-Nubian tribes were paying tribute to Egypt, although it is not know if this resulted from Egypt subduing the region through military-campaigns or whether it was though more peaceful trading-relationships.

3.2.3 12th Dynasty, Stability, and Empire

A wealth of written information from the 12th-Dynasty is found in literature, statues, temple inscriptions, inscription from military, mining, and trading expeditions, cemeteries, pyramids and tombs, and stela such as those of General Montuhotep and General Dedu-Intef.

Grajetzki (2006, p.28) suggests that the founder of the 12th-Dyansty, Amenemhat-I, had been Montuhotep-IV’s Vizier. Senusret-I succeeded the throne after a period of coregency and the ‘Instruction of King Amenemhat-I to his son Senusret [Sesostris]’ (Lichtheim, 1975, p.135-139) and the ‘Story of Sinuhe’ (Lichtheim, 1975, p.222-235) demonstrates that succession at the beginning of the Dynasty was contested (see-2.2.3.1).

Amenemhat expanded Egypt’s territory through military-might against the lands adjacent to Egypt (Libya, Western-Asia, and Nubia) and Senusret commanded some of the major military-campaigns (Grajetzki, 2006, p.31). Inscriptions in near Korosko (see-2.2.3.6) in Lower-Nubia (Figure-11.b) demonstrate that Egypt campaigned in Nubia before Amenemhat had reunited Upper and Lower Egypt. The ‘Instruction of King Amenemhat-I to his son Senusret [Sesostris]’ records that Amenemhat had ‘captured the Mejday’ and these skilled warriors may have been used in Amenemhat’s conflict with the Herakleopolitan House of Khety. I suggest that this demonstrates that controlling this region’s resources contributed to Egypt’s reunification.

Senusret-I continued his father’s policies of monumental building, maximizing trade via long-distance trade-routes and mining expeditions, and empire building (Grajetzki, 2006, p.36 and p.42). Senusret is credited with the consolidation of the Lower-Nubian Empire (Tyson-Smith, 2003, p.64). The policy towards Lower-Nubia can be deduced as one of prolonged military activity to establish Egyptian suzerainty - which was maintained by the strategic placement of fortresses and garrisons. Egyptian policy achieved the objectives of totally protecting and controlling their borders, trade-routes through Lower-Nubia to Egypt (Morkot, 2000, p.54), and access to prestige commodities (see-3.3.1). The 12th-Dynasty rulers, who succeeded Senusret, continued to evolve these policies and they employed military force and sustain Egypt’s Empire and uninterrupted economic wealth only when it was economically expedient.

The 200-year Classical-Period of the 12th-Dynasty came to an end without any indication of crisis (Grajetzki, 2006, p.63-74) and it was followed by the 13th-Dynasty. The 13th-Dynasty was a historically confused period where many Kings ruled for very short periods of time and, towards the end of the Dynasty, Grajetzki feels that national unity ended and a period of economic break-down ensued; the smaller Lower-Nubian fortresses fell into disuse and the strategic fortresses of Buhen slipped from Egyptian control.

3.3 Egypt’s interaction with Nubia

3.3.1 Demand for prestige goods

Adams (1977, p.165) succinctly described the Middle-Kingdom as a period of ‘armed trade monopoly’ operating through trading-posts. The regular supply of prestige commodities through Trade, or tribute, is significantly more efficient and predictable than acquisition via military means (Trigger, 1976, p.65-66).

Access to prestige commodities was vital to Egypt’s secular and religious stability and as Tyson-Smith (2003, p.73) explains it was vital to the legitimization of royal authority and that a major consumers of trade-goods were temples. This is demonstrated through the 12th-Dyansty text the ‘Admonitions of Ipuwer’ (Lichtheim, 1975, p.149-163) whose lamentation includes the loss of prestige goods when long-distance inter-nation trade-routes were interrupted during the First-Intermediate-Period (Tyson-Smith, 2003, p.60-61).

Egypt’s moneyless economy had a sustained but fragile demand for resources from Lower-Nubia such as gold, gem-stones, cattle, slaves, diorite (see3.4.1), Medjay mercenaries and resources from beyond Lower-Nubia such as ivory, ebony, animal-skins, oils, and incense (Tyson-Smith, 2003, p.58, Trigger/Kemp/O’Connor/Lloyd, 2001, p.123, and Welsby, 1998, p.12). This demand was not restricted to Lower-Nubia but also extended to the Levant, Mediterranean, and Punt.

3.3.2 Gold Mining in Lower-Nubia

Ancient mine-workings show that the exposed rocks of the Basement Complex in the desert east of Lower-Nubia (Figure-11.c) were the main sources of gold (Kirwan, 1974, p.266). The primary grouping of eastern gold mines ran along Wadi el-Allaqi (see3.1.3) and its exit to the Nile was protected and managed by mnwn-b3kl [Fortress of Kubban ((Foster, 2001, p.555)].

Open-cast mining and shallow-trench mining was within the eastern dessert dates to the Late Pre-Dynastic and early Dynasty periods (Klemm/Klemm/Murr, 2002, p.216). From the Old-Kingdom gold imports from Nubia are recorded, along with other precious commodities such as ivory, gems, animal skins, and people. Breasted (1906, p.215) recorded the Beni-Hassan tomb of Ameni who led soldiers of the Oryx Nome on expeditions into Nubia. Ameni returned with gold and gold-ore during Senusret-I’s reign (before his 43rd regnal-year). Ameni wrote that he returned without any loss to his soldiers and it is possible this was a mining expedition, using soldiers as manual-labour, rather than a military raid to cease gold and ore.

Klemm/Klemm/Murr (2002, p.216) wrote that Montuhotep’s campaign into Nubia was specifically to bring the gold-producing region under Egypt’s control and to eliminate the risk of interruption by indigenous peoples. This level of control may have been necessary because to process Gold Ore it initially had to be transported to a reliable source of water, which was most likely the Nile, and then gold was extracted from the gold-ore by crushing and washing (Vercoutter, 1959, p.126). Interestingly Edwards (2005, p.91) feels that impetus for the later campaigns of Senusret-III was to extend Egyptian control to include the gold-rich territory south of Buhen.

How much gold was extracted from Nubia during the Middle-Kingdom is not known (Vercoutter, 1959, p.133). During ThutmoseIII’s reign, when extraction/mining techniques were more evolved, an average of 250Kg of Wawat-Gold and 20Kg of Kush-Gold was brought into Egypt (Vercoutter, 1959, p.130).

3.3.3 Acculturation of Lower-Nubia

The interaction between Egypt and the Lower-Nubian population was an important matter for both peoples; without acceptable relationships it would be difficult to avoid conflict. On one ‘side’ was Egypt, who required stability and uninterrupted trade-routes; on the other were a subjugated people who might ‘resist’ their overlords. O’Connor (1993, p.55-56), using burial practices and grave-goods as a measure, does not perceive that acculturation [adoption by one society of the habit of another] was wide-spread during the Middle-Kingdom in Lower-Nubia. I consider that Egypt would have deliberately managed the local relationships carefully to preserve a respectful, yet firm, balance that achieved their objectives.

Where diverse peoples share an environment, such as Buhen or within the Egyptian military, the partial adoption of the more predominant material culture is possible. O’Connor (1993, p.56) stresses that there is little evidence for the adoption of Egyptian religious/ritual by Nubians but notes that during 25th-Dynasty when Nubia ruled Egypt there was assimilation of Egyptian culture. This strongly suggests that Egypt did not attempt to ‘convert’ Nubians into Egyptians and allowed cultural diversity to flourish. Tyson-Smith (2003, p.60) argues that ‘resisting’ acculturation and preserving ‘cultural solidarity’ was a deliberate decision by Nubians although I disagree and judge that Nubians were unlikely to have collectively determined to preserve their cultural integrity. Possibly General Montuhotep’s stela and his boastful statements of purging the indigenous population (see2.2.3.1) partially explains why Nubians did not elect to adopt Egyptian habits during the Middle-Kingdom.

3.4 Buhen to the Middle-Kingdom

3.4.1 Before the Middle-Kingdom

Inscriptions demonstrate that from the beginning of the Dynastic period and until 5th Dynasty rule of Djed-Ka-Re-Isesi Egypt made military-raids into Lower-Nubia (Morkot, 2000, p.45-46). The 4th-Dynasty King Sneferu recorded an expedition into Nubia that ‘Hacked up the people of Nehsyu” and captured 7,000 prisoners and 200,000 cattle. Inscriptions in Wadi el-Allaqi suggest that gold mining may have undertaken and the diorite quarries [North-West of Toshka, see Figure-11.b] were attested during the 5th-Dyansty by Djed-Ef-Re and during the 5th-Dynasty by Sahure and Djed-Ka-Re-Isesi.

Buhen-North may have been established as early as the 2nd-Dynasty (Morkot, 2000, p.47), although it is not possible to determine whether it was permanently occupied and Trigger/Kemp/O’Connor/Lloyd (2001, p.63) stress that the date is uncertain.

The Buhen-North settlement (Trigger/Kemp/O’Connor/Lloyd, 2001, p.125) was surrounded by a stone-wall and the material-culture was exclusively Egyptian. Significant evidence of copper-smelting was excavated (Welsby, 1998, p.170) and El-Gayar/Jones (1989, p.31) established that the ore contained a high proportion of gold but does not match any known local source of ore – it is probable that Buhen was re-processing ore that was traded from Upper-Nubia.

Inscriptional evidence at Buhen-North ends during the 5th-Dynasty (Trigger/Kemp/O’Connor/Lloyd, 2001, p.126). During the 6th-Dynasty (see2.2.2.2), when Lower-Nubia became hyper-arid, Egypt had lost control of Lower-Nubia and by necessity negotiated-trade replaced military-incursion (Morkot, 2000, p.47).

3.4.2 Middle-Kingdom Fortress of Buhen

Buhen is located down-stream of the 2nd-cataract on the western bank of the Nile (Figure-11.b). The oldest inscription found at Buhen dates to SenusretI’s 5th regnal-year (Lawrence, 1965, p.73), although it is possible that Senusret overbuilt an existing structure of AmenemhatI (Trigger/Kemp/O’Connor/Lloyd, 2001, p.130).

The fortress (Figure-11.a) was constructed on the Nile’s shelving-bank (Richards, 2005, p.231-235) in an area without any significant vegetation. It is 150-meters by 138-meters and was surrounded by a mud-brick enclosure-wall which was over 8-meters high and 5-meter thick. Military features include:

Semi-circular towers and loop-holds

Spur walls protecting the river-frontage

River-gates

Stone-lined tunnel connecting to the Nile for water-supply

Ditch, glacis, and ramparts (7.3-meters wide and 3.1-meters deep)

The fortress contained a complex of multi-floored buildings with a predominantly administrative/military purpose (Trigger/Kemp/O’Connor/Lloyd, 2001, p.131). The buildings, which were arranged on a grid, included:

Viceroy or Garrison Commander accommodation

Garrison head-quarters

Officer’s housing

Troop accommodation

Granaries

Workshops, including food/beer preparation

The fortress was enclosed by a 420-meters by 150-meters mud-brick wall which was 5.5-meter thick with towers and ditches; it enclosed 20-acres (Uphill, 1999, p.329).

Richards (2005, p.235) feels that this was a late Middle-Kingdom addition and the space between the fortress and enclosure-wall was multi-functional:

Actual use (determined by excavation)

Cemetery

Location of the Temple of Isis where General Montuhotep and General Dedu-Intef’s Stelae were discovered

Possible additional uses

Cattle-corrals

Training

Trading

Temporary accommodation for trading-expeditions/military-campaigns

It is not known how many people garrisoned the fortress although Trigger/Kemp/O’Connor/Lloyd (2001, p.131) feel that the garrison might have been modest. Emery (1965, p.153) estimates that during time of war, based on Buhen’s size, a garrison of 3,000 might have been required.

During the Middle-Kingdom a Viceroy of Nubia was appointed and it is likely that he was based at Buhen (Emery, 1965, p.148-149).

Adams (1976, p.182) believes that the Buhen’s garrison was predominantly Egyptian. Edwards (2005, p.93) and Tyson-Smith (2003, p.76) agree that during the 12th-Dynasty the garrison was regularly rotated (during the 13th-Dynasty a permanent garrison was introduced). The Semna Dispatches (see3.4.5) establishes that soldiers were from Egyptian Nomes.

The permanent garrison, like any town, would have required a mixture of occupations – with a focus on military skills. Some, but not all, must have included:

Administrators

Scribes

Priests

Translators

Soldiers

Armourers

Medjay trackers

Traders

Miners

Metal workers/processors

Bakers

Beer makers

Butchers

Porters and labourers

Ships crews and pilots

Messengers

Visiting officials

The resources expended to develop the defensive capabilities of Buhen were extensive and the Fortress was purpose-designed to ‘thwart a sophisticated type of siege’ (Richards, 2005, p.235).

The small indigenous population of Lower-Nubia (see3.1.4) was militarily unlikely to attack a fortress using siege warfare - although siege-engines were know by the Middle-Kingdom. I propose that the most probable reason for such a significant military-structure was the perceived threat from Upper-Nubia.

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

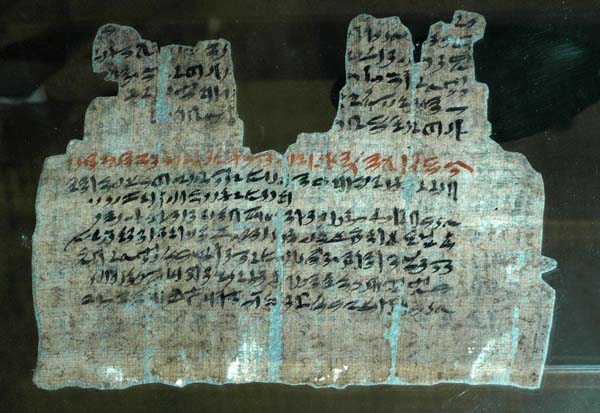

The Dispatches were copied to a number of people (Smither, 1945, p.10); Dispatch Number 10 was copied to the Judge of Hieraconpolis, the City-Administrator Ameny, and the High Stewart Senimeri. Regular dispatches would have been exchanged between Lower-Nubia and Egypt using a regular boat-service; this service would have imported supplies, such as soldiers, Barley, and Wheat and exported the dispatches and goods either traded or extracted in Lower-Nubia.

Many Museums contain Ancient Egyptian stelae, most are mortuary stelae dedicated to the memory of individuals. Only a small portion of stelae, such as General Montuhotep’s, contain information of historical importance and as O’Connor (1993, p.2-3) aptly explains that we add to our knowledge from three sources – from things, from people, and from places; Montuhotep’s stela certainly exemplifies this.

These stelae have three distinct yet entwined histories; firstly their creation by two 12th-Dynasty Generals in praise of their King, their nation, and their personal achievement, secondly the re-discovery of the stelae by people who played a part in the deciphering of Hieroglyphs, and thirdly the more contemporary interpretation of the stelae and the placement of these people and their actions within Ancient Egypt’s history.

Figure-1.a and Figure-1.b: William John Bankes

[Left] by George Sanders in 1812 (Shurmer, 2006, p.25), [Right] by Sir George Hayter in 1836 (Usick, 2002, p.187)

Unsigned, in the Department of Ancient Egypt and Sudan Study Room in the British Museum [photo by author]

Figure-3: Letter written by Thomas Young

Written to Henry Bankes on 10-February-1818. Held by the British Museum and currently within the Enlightenment Exhibition in the King’s Library [photo by author]

Figure-4: Obelisk and its red-granite base

Within the grounds of Kingston Lacy in Dorset [photo by author]

Figure-5.a: Ground Plan of North Temple of Isis at Buhen

William Bankes added detailed measurements of the temple. The stela of General Montuhotep was found in the location highlighted in Red and the Stelae of Dedu-Intef are highlighted in Green. Owned by the National Trust and held by the British Museum (XII.C.7) [photo by author].

Figure-5.b: Drawing of Buhen’s Northern Temple

Made by the EES Excavation in the 1960s (Caminos, 1974, Plate 83)

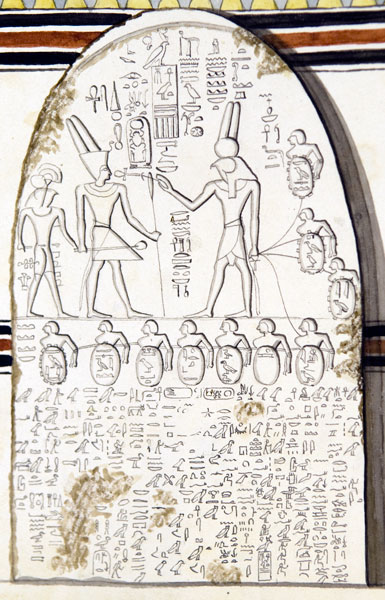

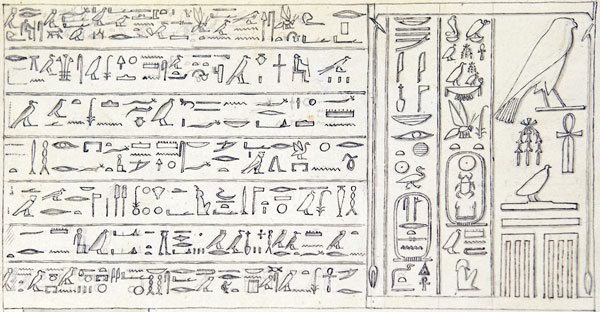

Figure-6.a: Stela of General Montuhotep

Stela discovered in the North Temple of Buhen was painted during Bankes excavation in 1819 by Dr. Alessandro Ricci in-situ. The ink, wash, and water colour painting owned by the National Trust and held by the British Museum (XII.C.6) [photo by author].

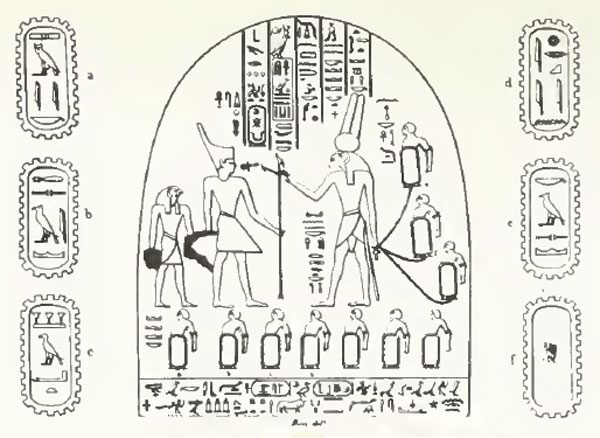

Figure-6.b: Stela of General Montuhotep

Franco-Tuscan expedition (1829) recovered the stela from Buhen and it was taken to Florence by Ippolito Rosellini (Champollion, 1844, Planche 1)

Figure-6.c: Rear wall of the central sanctuary

North Temple of Buhen was painted during Bankes excavation in 1819 by Dr. Alessandro Ricci in-situ. The ink, wash, and water colour painting owned by the National Trust and held by the British Museum (XII.C.6) [photo by author].

Figure-6.d: Stela of General Montuhotep

Stela from the North Temple at Buhen (2540a and 254bB) commemorating the victories of a Military Campaign in Nubia by General Montuhotep for Senusret I (Bosticco, 1959, Illustrazioni 29a and 29b).

Figure-7.a Drawing of the Dedu-Intef’s Stelae (EA 1177)

Discovered in the North Temple during Bankes excavation in 1819 (Usick, 2002, p.484/5); owned by the National Trust and held by the British Museum [photo by author]. Probably drawn by Henry Beechey in-situ (XII.C.5), the stela is held by the British Museum (EA 1177), seeFigure-7.c.

Figure-7.b: Drawing of Dedu-Intef’s Missing Stela

Drawing of the stela, now lost, discovered in the North Temple during Bankes excavation in 1819 (Usick, 2002, p.484/5); owned by the National Trust and held by the British Museum [photo by author]. Probably drawn by Dr. Alessandro Ricci in-situ (XII.C.4) and is the only representation of the ‘lost stela’

Figure-7.c: Dedu-Intef Steal EA 1177

Stelae discovered in the North Temple during Bankes excavation in 1819 is held in the Basement Store of the British Museum (EA 1177) [photo by author]

Figure-8: Sketch of Dr. Alexandro Ricci

by Salvatore Cherubini during the Franco-Tuscan expedition to Egypt in 1828-29 (Usick, 2002, p.141)

Figure-9: Painting of Jean-François Champollion

by Léon Cogniet 1831 (Champollion, 2005, p.19)

Figure-9: Photo of Colonel Sir Henry George Lyons, F.R.S.

(Dale, 1944, between p.795 and p.796)

Figure-10: Contemporary Arched Roof

Example of Sudanese construction technique utilizing a series of arched roofs (Randall-MacIver/Woolley, 1911b, Plate 2)

During the later Middle Kingdom with the Northern Temple overlaid in Red (Emery/Smith/Millard A, 1979, Plate-3 and Plate-4)

Figure-11.b: Region between Aswan and the Island of Sai

(Morkot, 2000, p.4)

Figure-11.c: Gold Mining in Upper Egypt and Lower-Nubia

(Trigger, 1976, p.66)

Figure-12.a: Models of Soldiers

Troop of 40 Egyptian soldiers from Prince Mesehti’s tomb at Asyut which dates to the 11th-Dynasty (Tiradritti, 1999, p.108/109) [photo by author].

Figure-12.b: Models of Soldiers

Troop of 40 Nubian archers from Prince Mesehti’s tomb at Asyut which dates to the 11th-Dynasty (Tiradritti, 1999, p.108/109) [photo by author].

Figure-13: Statue of Senusret I

Held by the Luxor Museum [photo by author]

Figure-14: Tomb of Montuhotep at Lisht-South

(Arnold, 2008, Plate 77a)

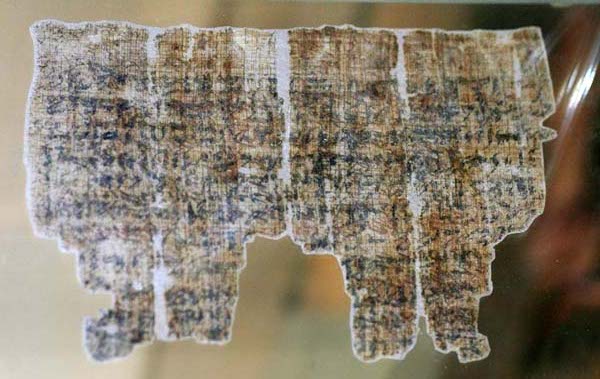

Held by the British Museum, EA 10752 [photo by author] containing part of Dispatch Number 3 and Dispatch Number 4.

eld by the British Museum, EA 10753 [photo by author] containing magical texts.

6 Bibliography

Sources referenced within this Dissertation

|

Adams, W |

(1977) |

Nubia, Corridor to Africa |

London: Penguin Books |

|

Adkins, L and Adkins, R |

(2001) |

The Keys of Egypt, The race to crack the Hieroglyph Code |

New York: HarperCollins Publishers |

|

Arnold, D |

(2003) |

The Encyclopaedia of Ancient Egyptian Architecture |

London: I. B. Tauris |

|

Arnold, D |

(2008) |

Middle Kingdom Tomb Architecture at Lisht |

New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|

|

(1980) |

|

Oxford: Andromeda Oxford Limited |

|

|

(1923) |

|

Unpublished |

|

Bell, L |

(2005) |

‘The New Kingdom Divine Temple’ in Shafer B, Arnold D, Haeny G, Bell L, Finnestad R, Temple of Ancient Egypt |

London: I. B. Tauris |

|

Bosticco, S |

(1959) |

Museo Archeologico di Firenze, Le Stele Egiziane, Parte I |

Rome: Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato |

|

|

(1906) |

|

Chicago: University of Chicago Press |

|

Brooklyn Museum (no author listed) |

(1978) |

Africa in Antiquity |

New York: The Brooklyn Museum |

|

Caminos, R |

(1974) |

The New-Kingdom Temples of Buhen, Volume II |

London: Egyptian Exploration Society |

|

Caminos, R |

(1998) |

Semna-Kumma II: The Temple of Kumma |

London: Egyptian Exploration Society |

|

Champollion, J-F |

(1844) |

Monuments de L’Egypte, et de la Nubie; Volume 1 |

Geneve: Centre de Documentation du Monde Oriental |

|

Champollion, J-F |

(2001) |

Egyptian Diaries |

London: Gibson Square Books |

|

Champollion, J-F |

(2005) |

Egypte, Lettes et Journaux de voyage |

Éditions de Lodi |

|

Dale, H |

(1944) |

Henry George Lyons. 1864-1944 |

Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society, Vol. 4, No. 13 (Nov., 1944), pp. 795- 809 |

|

|

(2004) |

|

London: Thames and Hudson |

|

Dowson, E |

(1945) |

Colonel Sir Henry Lyons, F.R.S. |

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 31 (Dec., 1945), pp. 98-100 |

|

Edwards, D |

(2005) |

The Nubian Past; An Archaeology of the Sudan |

Abingdon: Routledge |

|

Edwards, I, Gadd, C, Hammond, N, and Sollberger, E |

(1973) |

The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume II part 1: The Middle East and the Aegean Region c.1800-1380 BC

|

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press |

|

El-Gayar, S and Jones M |

(1989) |

A Possible Source of Copper Ore Fragments Found at the Old Kingdom Town of Buhen |

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 75, (1989), pp. 31-40 |

|

Emery W, Smith H, and Millard A |

(1979) |

The Fortress of Buhen; The Archaeological Report |

London: Egyptian Exploration Society |

|

Emery, W |

(1965) |

Egypt in Nubia |

London: Hutchinson |

|

Fabre, D |

(2005) |

Seafaring in Ancient Egypt |

London: Periplus Publishing |

|

Faulkner, R |

(1953) |

Egyptian Military Organization |

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 39, (Dec., 1953), pp. 32-47 |

|

Fields, N |

(2007) |

|

|

|

Finati, G |

(1830) |

Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Giovanni Finati, Native of Ferrara. Volume II |

London: John Murray |

|

|

(2001) |

|

Oxford: Oxford University Press |

|

Frothingham, A |

(1894) |

Archaeological News |

The American Journal of Archaeology and of the History of the Fine Arts, Vol. 9, No. 2 (Apr. - Jun., 1894), pp. 229-330 |

|

|

(1916) |

|

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 3, No. 2/3, (Apr. - Jul., 1916), pp. 184-192 |

|

Goedicke, H |

(1981) |

Harkhuf's Travels |

Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 40, No. 1 (Jan., 1981), pp. 1-20 |

|

Gohary, J |

(1998) |

Guide to the Nubian Monuments on Lake Nasser |

Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press |

|

Grajetzki, W |

(2006) |

The Middle Kingdom of Ancient Egypt |

London: Gerald Duckworth |

|

Hayes, W |

(1961) |

The Middle Kingdom in Egypt |

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press |

|

Hooker, J |

(2004) |

Reading the Past |

London: The British Museum Press |

|

James, T |

(1997) |

Egypt Revealed; Artist-Travellers in an Antique Land |

London: The Folio Society |

|

|

(2001) |

|

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press |

|

Kemp, B |

(2006) |

Ancient Egypt; Anatomy of a Civilization (2nd Edition) |

Abingdon: Routledge |

|

|

(1974) |

|

The Geographical Journal, Vol. 140, No. 1 (Feb., 1974), pp. 43-51 |

|

|

(2002) |

|

London: The British Museum Press |

|

|

(1946) |

|

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 32 (Dec., 1946), pp. 57-64 |

|

|

(1965) |

|

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 51, (Dec., 1965), pp. 69-94 |

|

|

(1993) |

|

Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 113, No. 3, (Jul. - Sep., 1993), pp. 423- 436 |

|

Lichtheim, M |

(1975) |

Ancient Egyptian Literature: Volume 1: The Old and Middle Kingdoms |

Berkeley: The University of California Press |

|

Manley, D and Rée P |

(2001) |

Henry Salt; Artist, Traveller, Diplomat, Egyptologist |

London: Libri Publications |

|

Masson, O |

(1978) |

Carian Inscriptions from North Saqqara and Buhen |

London: Egyptian Exploration Society |

|

Morkot, R |

(2000) |

The Black Pharaohs |

London: The Rubicon Press |

|

|

(2001) |

|

Oxford: Oxford University Press |

|

Nicoll, F |

(2004) |

The Mahdi of Sudan and the death of General Gordon |

Stroud: Sutton Publishing |

|

O’Connor, D |

(1978) |

‘Egypt in Nubia during the Old, Middle, and New Kingdom’ (no author listed) in Africa in Antiquity |

New York: The Brooklyn Museum |

|

O’Connor, D |

(1986) |

The Locations of Yam and Kush and Their Historical Implications |

Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, Vol. 23, (1986), pp. 27-50 |

|

O’Connor, D |

(1993) |

Ancient Nubia, Egypt’s Rival in Africa |

Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania |

|

Parkinson, R |

(1999) |

Cracking Codes; the Rosetta Stone and Decipherment |

London: British Museum Press |

|

|

(2004) |

|

London: British Museum Press |

|

|

(1995) |

|

Oxford: Thee Griffith Institute |

|

|

(1911a) |

|

Philadelphia: University Museum Philadelphia |

|

|

(1911b) |

|

Philadelphia: University Museum Philadelphia |

|

Richards, J |

(2005) |

Society and Death in Ancient Egypt; Mortuary Landscape of the Middle Kingdom |

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press |

|

Sadek, A |

(1980) |

The Amethyst Mining Inscriptions of Wadi El-Hudi; Part I: Text |

Warminster: Aris & Phillips |

|

Sandes, E |

(1937) |

The Royal Engineers in Egypt and the Sudan |

Chatham: Institution of the Royal Engineers |

|

Sebba, A |

(2004) |

The Exiled Collector |

London: John Murray |

|

|

(2001) |

|

Oxford: Oxford University Press |

|

Shaw, I |

(2002) |

The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt |

Oxford: Oxford University Press |

|

|

(2006) |

|

Great Britain: The National Trust |

|

Simpson, W |

(1978) |

The Literature of Ancient Egypt |

New Haven: Yale University Press |

|

Smith, H |

(1976) |

The Fortress of Buhen; the Inscriptions |

London: Egyptian Exploration Society |

|

|

(1945) |

|

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 31 (Dec., 1945), pp. 3-10 |

|

|

(2007) |

‘Comparative Temples of the Early Nineteenth Dynasty’ in Snape, S and Wilson, P, Zawiyet Umm El-Rakham I, The Temples and Chapels |

Bolton: Rutherford Press |

|

Stefanovié, D |

(2007) |

’ aHAwtywof the Middle Kingdom’ in Grallert, S and Grajetzki, W, Life and Afterlife in Ancient Egypt during the Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period |

London: Golden House Publications |

|

|

(1996) |

|

Science, New Series, Vol. 274, No. 5293 (Dec. 6, 1996), pp. 1696-1698 |

|

Tiradritti, F |

(1999) |

Egyptian Treasures from the Egyptian Museum in Cairo |

New York: Harry N Abrams |

|

Trigger, B |

(1976) |

Nubia under the Pharaohs |

London: Thames and Hudson |

|

Trigger, B, Kemp, B, O’Connor, D, Lloyd, A |

(2001) |

Ancient Egypt, A Social History |

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press |

|

Tyson-Smith, S |

(2003) |

Wretched Kush |

London: Routledge |

|

|

(1999) |

‘Nubian Settlement Fortifications in the Middle-Kingdom’ in Leahy, A and Tait, J, Studies in Ancient Egypt , in Honour of H. S. Smith |

London: The Egypt Exploration Society |

|

Usick, P |

(1998a) |

William John Bankes’ Collection of Drawings and Manuscripts to Ancient Nubia, Volume I (a Thesis submitted to the University of London for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy) |

London: British Library, Thesis Service |

|

Usick, P |

(1998b) |

William John Bankes’ Collection of Drawings and Manuscripts to Ancient Nubia, Volume II, Part 2 (a Thesis submitted to the University of London for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy) |

London: British Library, Thesis Service |

|

|

(1999) |

‘The First Excavation of Wadi Halfa (Buhen)’ in Leahy, A and Tait, J, Studies in Ancient Egypt , in Honour of H. S. Smith |

London: The Egypt Exploration Society |

|

Usick, P |

(2002) |

Adventures in Egypt and Nubia; the Travels of William John Bankes (1786 – 1855) |

London: The British Museum Press |

|

Usick, P |

(2006) |

‘William John Bankes in Egypt’ in Demarée, R, The Bankes late Ramesside Papyri |

London: The British Museum Press |

|

Vercoutter, J |

(1959) |

Gold of Kush, the Gold Washing stations at Faras East |

Kush 7 (1959), pp. 120-153 |

|

|

(2001) |

|

Oxford: Oxford University Press |

|

Welsby, D |

(1998) |

|

|

|

Wilkinson, R |

(2003) |

The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt |

London: Thames and Hudson |

|

Internet_1 |

Times Online Archive |

The Times Newspaper Group |

https://www.timesonline.co.uk/ (accessed 18-Feb-2009) |

|

Internet_2 |

Hieroglyphic Dictionary |

Author |

https://www.ancient-egypt.co.uk/ (accessed 25-Apr-2009) |

|

Internet_3 |

College Index |

University of Cambridge |

https://www.cam.ac.uk (accessed 08-May-2009) |

Sources used for research, not referenced within this Dissertation

|

|

(1984) |

|

Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol. 26, No. 1, (Jan., 1984), pp. 36-71 |

|

|

(1970) |

|

Metropolitan Museum Journal, Vol. 3, (1970), pp. 27-50 |

|

|

(1991) |

|

Metropolitan Museum Journal, Vol. 26, (1991), pp. 5-48 |

|

|

(1958) |

|

Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 17, No. 4, (Oct., 1958), pp. 263-268 |

|

|

(1970) |

|

The Geographical Journal, Vol. 136, No. 4 (Dec., 1970), pp. 569-573 |

|

|

(1971) |

|

American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 75, No. 1 (Jan., 1971), pp. 1-26 |

|

|

(1975) |

|

American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 79, No. 3 (Jul., 1975), pp. 223-269 |

|

Belzoni, G |

(2001) |

Belzoni’s travels; Narrative of the Operations and Recent Discoveries in Egypt and Nubia, edited by Alberto Siliotti |

London: British Museum Press |

|

|

(1969) |

|

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 55, (Aug., 1969), pp. 216-216 |

|

|

(1994) |

|

Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, No. 294, (May, 1994), pp. 7-22 |

|

|

(1999) |

|

Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, No. 315, (Aug., 1999), pp. 47-74 |

|

Caminos, R |

(1974a) |

The New-Kingdom Temples of Buhen, Volume I |

London: Egyptian Exploration Society |

|

|

(1998) |

|

London: Egyptian Exploration Society |

|

Caminos, R |

(1998) |

Semna-Kumma II: The Temple of Kumma |

London: Egyptian Exploration Society |

|

|

(1916) |

|

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 3, No. 2/3, (Apr. - Jul., 1916), pp. 155-179 |

|

|

(1933) |

|

Biometrika, Vol. 25, No. 3/4, (Dec., 1933), pp. 254-284 |

|

|

(1950) |

|

D'ARCHÉOLOGIE ORIENTALE |

|

|

(1992) |

|

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 78, (1992), pp. 274-279 |

|

Drower, M and Sorrell A |

(1970) |

Nubia: A Drowning Land |

Ipswich: W S Cowell |

|

|

(1942) |

|

Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 1, No. 3, (Jul., 1942), pp. 307-314 |

|

|

(1982) |

|

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 68 (1982), pp. 126-133 Published |

|

|

(2004) |

|

London: Sage Publications |

|

|

(1976) |

|

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 62, (1976), pp. 176-176 |

|

|

(1961) |

|

American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 65, No. 1, (Jan., 1961), pp. 68-69 |

|

|

(1955) |

|

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 41, (Dec., 1955), pp. 9-17 |

|

Goedicke, H |

(1995) |

Studies about Kamose and Ahmose |

Baltimore: Halgo |

|

Grajetzki, W |

(2003) |

Burial Customs in Ancient Egypt |

London: Gerald Duckworth |

|

|

(1995) |

|

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 81, (1995), pp. 43-56 |

|

|

(1998) |

|

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 84, (1998), pp. 201-205 |

|

Grimal, N |

(1992) |

A History of Ancient Egypt |

Oxford: Blackwell Publishers |

|

|

(1962) |

|

Worcester: Ebenezer Baylis |

|

|

(1965) |

|

Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol. 7, No. 4, (Jul., 1965), pp. 461-480 |

|

|

(1972) |

|

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 58, (Aug., 1972), pp. 225-244 |

|

|

(1964) |

|

Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 23, No. 2, (Apr., 1964), pp. 73-114 |

|

Irby, C and Mangles, J |

(1844) |

Travels in Egypt and Nubia, Syria, and the Holy Land |

London: John Murray |

|

|

(1953) |

|

Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 12, No. 1, (Jan., 1953), pp. 51-55 |

|

|

(1963) |

|

The Geographical Journal, Vol. 129, No. 3, (Sep., 1963), pp. 261-273 |

|

Lane, E |

(2001) |

Description of Egypt |

Cairo: American University Press |

|

|

(2006) |

|

Chicago: The Oriental Institute |

|

Leahy, A and Tait, J |

(1999) |

Studies on Ancient Egypt in Honour of H. S. Smith |

London: Egyptian Exploration Society |

|

|

(1993) |

|

Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, No. 290/291, (May - Aug., 1993), pp. 29-94 |

|

|

(1909) |

|

The Geographical Journal, Vol. 34, No. 1, (Jul., 1909), pp. 36-51 |

|

|

(1916) |

|

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 3, No. 2/3 (Apr. - Jul., 1916), pp. 182-183 |

|

Madden, R |

(1829) |

Travels in Turkey, Egypt, Nubia, and Palestine in 1824, 1825, 1826, and 1827 |

London: Henry Colburn |

|

Madox, J |

(1834) |

Excursions in the Holy Land, Egypt, Nubia, Syria, &c; Volume 1 |

London: Richard Bentley |

|

Manley, B |

(1996) |

The Penguin Historical Atlas of Ancient Egypt |

London: Penguin Books |

|

|

(1939) |

|

The Geographical Journal, Vol. 94, No. 2 (Aug., 1939), pp. 97-111 |

|

Murray, J |

(1900) |

Hand Book for Egypt |

London: John Murray |

|

O’Connor, D |

(1987) |

The Location of Irem |

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 73, (1987), pp. 99-136 |

|

Parkinson, R |

(2008) |

The Painted Tomb-Chapel of Nebamun |

London: British Museum Press |

|

|

(1947) |

|

Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 67, No. 2 (Apr. - Jun., 1947), pp. 127- 135 |

|

|

(1994) |

|

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 80, (1994), pp. 145-158 |

|

Reisner G, and Wheeler, N |

(1967) |

Second Cataract Forts, Volume II |

Boston: Museum of Fine Arts |

|

|

(1949) |

|

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 35 (Dec., 1949), pp. 50-58 |

|

|

(1993) |

|

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 79, (1993), pp. 81-97 |

|

|

(1996) |

|

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 82, (1996), pp. 181-192 |

|

|

(1959) |

|

Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 18, No. 1 (Jan., 1959), pp. 20-37 |

|

|

(1972) |

|

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 58 (Aug., 1972), pp. 43-82 |

|

|

() |

|

|

|

|

(1976) |

|

The International Journal of African Historical Studies, Vol. 9, No. 1, (1976), pp. 1-21 |

|

|

(1975) |

|

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 61, (1975), pp. 67-101 |

|

|

(1843) |

|

New York: C.S. Francis |

|

|

(1966) |

|

American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 70, No. 1, (Jan., 1966), pp. 71-71 |

|

Usick, P |

(1998b) |

William John Bankes’ Collection of Drawings and Manuscripts to Ancient Nubia, Volume II, Part 1 (a Thesis submitted to the University of London for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy) |

London: British Library, Thesis Service |

|

|

(1996) |

|

Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 55, No. 4, (Oct., 1996), pp. 249-279 |

|

|

(1916) |

|

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 3, No. 2/3, (Apr. - Jul., 1916), pp. 180-181 |

|

Welsby, D and Anderson, R |

(2004) |

|

|

|

|

(1995) |

|

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 81, (1995), pp. 77-94 |

|

|

(1976) |

|

Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 35, No. 2, (Apr., 1976), pp. 127-130 |

|

|

(2003) |

|

London: Routledge |

|

|

(1975) |

|

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 61, (1975), pp. 42-44 |

|

|

(1972) |

|

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 58, (Aug., 1972), pp. 83-90 |

Contact & Feedback : Egyptology and Archaeology through Images : Page last updated on 21-November-2025

: