Description De L'Egypte

Description De L'Egypte

This work published in 1808 in 23 volumes is, for an egyptologist, breathtaking. It was re-printed in 1820 and still hold a commanding respect for its quality, breadth and vitality. Even more interesting is the way that it came about, through war, personal ambition, a thirst for knowledge and discover and maybe 'killing time' until a release from Egypt could be obtained.

A recent publication, 2003 ISBN 88-8095-902-6, authored by Franco Serino has pulled together some of the most interesting plates with text into a short history of Description de l'Egypte. Franco Serino, a former lecturer in Foreign Literature and Languages, has used his long interest in Egypt especially the rediscovery by European travellers and scholars very well. His text, example of which follow, provides a good grounding in Napoleon's Oriental ambition and the impact his 'savants' have had on a European fascination with Egyptology.

- France's Military ambitions for the Orient

- "No sooner did the sun disappear over the horizon than the immense French fleet approached the canal. Upon seeing the surface of the sea covered with ships, the inhabitants of Alexandria were seized with fright and terror." Histoire de I expedition des Francais en Egypte.

On 1-July-1798 a French fleet, carrying the twenty-nine year-old Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821), consisting of over 300 transport and war ships and about 50,000 men was about to disembarked at Alexandria. This was the beginning of the Egyptian campaign. This Oriental expedition was an alternative to an invasion of England, France's long-time enemy. Napoleon had decided to organize it with the political aim of challenging British control of the Mediterranean and thus interrupting the critical trade routes to India.

- The Orient had always fascinated Napoleon and he once stated, "Nothing great can be achieved except in the Orient." Egypt's strategic position made it key to the British Orient, which was virtually a gateway to the region. But what was Egypt like at the end of the 18th century?

The country had been invaded and conquered by the Arabs in AD 639, becoming part of the Islamic world and almost totally cutting its ties with Europe. After the Mamluks dominion, an old military oligarchy of Turkish-Circassian origin (1250-1517), the Turkish sultan Selim I (the Grim) took control of Egypt. It became a province of the vast Ottoman Empire governed by a pasha chosen by the sultanate in Constantinople. The country's economic and social conditions worsened continuously because of the various military insurrections, epidemics and famine. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the French historian Edouard Driault summed up, "Egypt had indeed disappeared from history, cast into a corner of the Mediterranean, at the mercy of anarchy and misery and therefore almost restored to the desert, to the void."

-

When Napoleon arrived in Alexandria, he found a country with a

population of less than three million,

still virtually governed by the Mamluks, in an extremely precarious

condition because of the instability and difficulties in all spheres, both

public and private. Within a week of landing, Napoleon began his

ill-planned and ill-supplied march

to the interior. On 21-July defeated Murad Bey's Mamluk army in the famous 'Battle of

the Pyramids,' and on 24-July, made his triumphal entrance into Cairo.

Dreams of glory and conquest were

dashed a few days afterward by destruction of the fleet by Horatio Nelson at Abukir Bay. The Armee d'Orient thus found itself

very isolated without means of receiving aid or supplies - or escape.

When Napoleon arrived in Alexandria, he found a country with a

population of less than three million,

still virtually governed by the Mamluks, in an extremely precarious

condition because of the instability and difficulties in all spheres, both

public and private. Within a week of landing, Napoleon began his

ill-planned and ill-supplied march

to the interior. On 21-July defeated Murad Bey's Mamluk army in the famous 'Battle of

the Pyramids,' and on 24-July, made his triumphal entrance into Cairo.

Dreams of glory and conquest were

dashed a few days afterward by destruction of the fleet by Horatio Nelson at Abukir Bay. The Armee d'Orient thus found itself

very isolated without means of receiving aid or supplies - or escape.

- Bonaparte embarked on a military campaign northwards into Syria against the Ottoman Empire which, allied with Great Britain, had declared war against France. After some initial successes, the 3 month campaign failed. Napoleon's idea of holding Egypt proved to be impossible. On hearing of a political, and personal, threat in Paris Napoleon to abandon Egypt in August and return to France, leaving General Kleber in charge of his troops. Kleber wasn't aware that Napoleon was leaving until after he had left for France! The unsupplied army of occupation found itself in an extremely difficult situation: hostility and revolts , assassination of Kleber in June 1800, inept generals and defeats suffered by generals Belliard and Menou, at the hands of the British in 1801, forced a total capitulation. From a military perspective , the 'Oriental Expedition' was a total, and costly, failure.

-

- The first consequence of the failure of the military campaign in Egypt was the return of Egypt, the most important country in North Africa, to the British empire, which was traditionally hostile to France.

- France's Scientific ambitions in Egypt

- The army contingent, in addition to military forces, included a group of 154 'savants' - engineers, architects, mathematicians, chemists, orientalists, physicians, natural scientists, artists and others. They had embarked on a journey whose destination was kept secret from almost all the members and was revealed at sea and after Malta had been captured.

- These scholars put trust in Bonaparte: their revolutionary spirit, love of the ancient world, thirst for knowledge or excitement over an unknown but prestigious enterprise for French Republic were instrumental in their accepting the risks and dangers involved in the mission. Napoleon was gifted with intuition and an exceptional interest and perception of history. He knew that scientific conquests might prove to be more important than just military victories. He said "We must hold scientists in great esteem and support science." So the French expedition included the Commission des Sciences et des Arts (group's official name) which was tasked to explore, make drawings and write descriptions of all aspects of Egypt, which was for the most part unknown at that time.

- The first consequence of the failure of the military campaign in Egypt was the return of Egypt, the most important country in North Africa, to the British empire, which was traditionally hostile to France.

- France, whose

'regenerative mission' would leave a remarkable scientific and cultural

heritage for all of Europe. Napoleon, the 'civilizing hero', mindful of

Alexander the Great, planned to reveal a civilization that had

disappeared two thousand years earlier and had played a

vital role in Mediterranean history.

- The Institute L'Egypte

- 0n 22-August-1798, a project that Napoleon had nurtured came into being: the foundation in Cairo of the Institut l'Egypte, modelled after the Institut de France. The main aim was to 'porter les lumieres' to Egypt, that is to say, disseminate progress and culture, support research, and publish the history of ancient and modern Egypt, including its customs and traditions. The original thirty-six members of this institute were chosen from among leading experts and scholars in various fields. Gaspard Monge was elected the first president. During its short-lived existence (three years), the Institut d'Egypte was forced to elect new members because some were killed in battle or died of illness, and others were sent back to France. Of the 154 original savants 34 died.

- Rosetta Stone

- In July 1799, during the Napoleonic campaign,

excavations effected at Fort Julien, near the village of al-Rashid (Rosetta)

east of Alexandria, brought to light a find that proved to be of fundamental

importance to the future science of Egyptology. This was the 'Rosetta

Stone' discovered by the French officer Pierre Bouchard and now in

the British Museum.

- The black granite slab is 114 cm long, 72 cm wide, and 28 cm

thick and weighs 760 kilograms. It dates from 196 BC within the Ptolemaic

Dynasty. An incomplete text was carved on the stone in three

scripts - hieroglyphs, demotic and Greek.

- Bonaparte's scholars believed that the three inscriptions were versions of the same text, so by starting off from the Greek, they felt they might be able to decipher hieroglyphic script, which had been incomprehensible for 14 centuries. Jean-Francois Champollion succeeded in deciphering hieroglyphic text in September 1822.

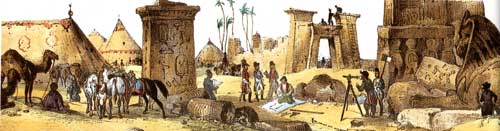

- Even thousand years after ancient Egypt's time, the French scholars, also many soldiers, were spellbound by the history of Egypt. This is why the savants were eager to gain knowledge of everything they could: nature, all facets of Egyptian society, and in particular monuments built during the three thousand years of the country's history and left as a cultural heritage for future generations.

-

General Desaix pursued the retreating Mamluks towards Upper Egypt. About twenty scholars were part of the military contingent that reached

Aswan on 2-February-1799. These included the Jean-Baptiste Jollois

and Edouard de Villier, as well as the 'veteran' Dominique Vivant Denon, ". . . who ran towards the

monuments like soldiers run to the battlefield." Denon in particular

journeyed through Egypt drawing continuously - he drew everything he saw: landscapes, battles,

ceremonies, mosques, various personages, and, above all, the ancient ruins.

General Desaix pursued the retreating Mamluks towards Upper Egypt. About twenty scholars were part of the military contingent that reached

Aswan on 2-February-1799. These included the Jean-Baptiste Jollois

and Edouard de Villier, as well as the 'veteran' Dominique Vivant Denon, ". . . who ran towards the

monuments like soldiers run to the battlefield." Denon in particular

journeyed through Egypt drawing continuously - he drew everything he saw: landscapes, battles,

ceremonies, mosques, various personages, and, above all, the ancient ruins.

Denon, in July 1799, returned to Cairo. Napoleon was impressed by his drawings, which represented a fairly complete picture of Egypt, both ancient and modern. Although Denon had succeeded in doing all that work by himself, it was important to do even more. The following month two special commissions, each with a dozen scholars, left for Upper Egypt with the task of visiting and describing all the remaining monuments. A month later they met at Philae, the southernmost point in the journey, and began to sail down the Nile in the direction of Cairo.

- The savants made topographical surveys, drew the ancient ruins, measured the monuments, and carefully copied the hieroglyphic texts. There were attacks and they were obliged to suspend their work and, in order to be protected by the troops that closed their ranks, the scholars had to obey the famous order that inevitably made the soldiers laugh: "Donkeys and scholars in the middle!" In such circumstances, even copying hieroglyphs, whose meaning was still undecipherable, was often a superficial procedure at best. And in their hypothetical reconstructions of some monuments, the artists made use of all their ability, going so far as to 'imagine' the decoration that no longer existed by re-creating scenes they had seen on other ancient ruins.

Another important part of the Commission's work that should be mentioned was their drawings of monuments which, for various reasons, no longer exist today. In the descriptions of the illustrations selected for this volume, we have included monuments that were destroyed in the first half of the nineteenth century. Mohammed Ali, the founder of modern Egypt, implemented a wide-ranging program of reforms and renewal for his country, as he was eager to lead his country out of the 'dark ages' of the preceding centuries. But in doing so, he was often insensible to his nation's glorious past, allowing monuments to be demolished.

-

Some, but not all, French

generals contributed to the scientific and cultural success of the

Egyptian campaign. Among those who showed interest in ancient Egyptian

history and monuments, mention should be made at least of Louis Charles Desaix (1768-1800)

[see above picture] and Jean-Baptiste Kleber (1753-1800)

[see picture to right]. Desaix,

a young general, combined the qualities of military strategist with the erudition of a scholar and noteworthy artistic

taste. He may have to have discovered the famous zodiac relief at Dendera

(original is in the Louvre and Dendara has a copy in situ).

Some, but not all, French

generals contributed to the scientific and cultural success of the

Egyptian campaign. Among those who showed interest in ancient Egyptian

history and monuments, mention should be made at least of Louis Charles Desaix (1768-1800)

[see above picture] and Jean-Baptiste Kleber (1753-1800)

[see picture to right]. Desaix,

a young general, combined the qualities of military strategist with the erudition of a scholar and noteworthy artistic

taste. He may have to have discovered the famous zodiac relief at Dendera

(original is in the Louvre and Dendara has a copy in situ).

General Kleber, was a cultured man who had studied architecture. He came up with the idea of creating a 'work in common'. In November 1799, he was enthusiastic about the drawings made by the two commissions that had returned from Upper Egypt and wrote, "One cannot but laud the amazing activity, the predominant harmony, and the precise division of labour among the members of the two commissions, and above all the liberal and patriotic idea of combining so much information into a single work..." The aim of the work on Egypt was to "... spread culture and help to build a literary monument worthy of France."- This major work was of course to become the Description de l'Egypte, the most remarkable heritage of the Napoleonic expedition. The physicist Joseph Fourier was charged with coordinating the contributions, but he had to interrupt the preparation of the publication in 1801 when the French left Egypt, so it was continued and completed in Paris during the years that followed. It was a set of circumstance that gave the means to study Egypt with the attention it deserved.

- France had made little effort to plan Egypt's conquest, but every

artistic effort was made to describe it. A great number of draftsmen,

painters, skilled typographers, mechanics and about four hundred

engravers devoted themselves to task. The publication, dedicated to the

description of so many outstanding monuments is itself a colossal work

in the field of literature, science and art.

- After the French returned from Egypt, a consular decree of February 1802 announced the publication, at the government's expense, of the "...results in science and art obtained during the Expedition." This was the Description de l'Egypte. Written by a group of about fifty scholars whose contributions were coordinated by the physicist Joseph Fourier, the work involved about two thousand people and took about twenty years to complete. The gifted Nicolas-Jacques Conte invented a special, larger typographical machine, new printing methods were realized for the colour plates, and special paper was utilized, particularly for the engravings.

- Surrender and Return to France

- In March 1801, in the wake of the military defeats and capitulation, the remaining group of scholars returned to France, each taking along his drawings, notes and collections, after having to overcome many an obstacles. The British confiscated archaeological finds including the Rosetta stone.

- Article 16 of the French surrender, written at Alexandria on 3-September-1801, stipulates that, "The members of the Institut can take with them all the artistic tools brought from France; but the Arab manuscripts, statues, and other collections created for the French Republic shall be considered 'public property' and be placed at the disposal of the army generals." At this point the naturalists Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire and Raffeneau Delile, who represented the French Commission, threatened to burn all the collections if the French scholars were not allowed to take with them their 'intellectual property," that is, drawings, notes, and collections. General Hutchinson, the Englishman negotiating the French capitulation, concerned that unpleasant consequences might arise, allowed the savants to keep all their scientific information and collections. The British took possession of the archaeological finds, which included the Rosetta Stone.

- The 1st edition of Description de l'Egypte

- Published in Paris between 1809 and the first edition of the Description de

l'Egypte ou Recueil des observations et des recherches qui faites en Egypte pendant

l'expedition de l'armee frances publie par les odres de sa Majeste l'Empereur

Napoleon le

Grand [Description of Egypt or collection of observations and research

made during the French Expedition in Egypt published on the orders of

Emperor Napoleon] consists of ten volumes of text and

thirteen volumes of illustrations in folio plates (including two complementary

volumes and an atlas). The volumes are groups into three distinct sets, Antiquites,

Etat Moderne and Histoire Naturelle. 1000

copies were printed.

- The Antiquites section, which is Franco Serino's book presents, is the most fascinating dealing with the archaeology ancient Egyptian, Ptolemaic, and Roman and includes all the pre-Islamic sites and monuments visible at the time of the Egypt campaign. The plates are excellent and they were reduced to the minimum length considered indispensable. The plates were ordered from south (Upper) to north (Lower), from the island of Philae to the Mediterranean.

- The Etat Moderne features medieval and modern Egypt, Islamic architecture, and Egyptian customs, arts, crafts, and trades up to and including the 18th century. The Histoire Naturelle contains descriptions and illustrations of animals and plants, classifications of minerals and the results of research in various fields, including arms, music etc.

- The 2nd edition of Description de l'Egypte

- In 1820 the publisher Charles-Louis Panckoucke printed the second edition of

the Description, which was dedicated to Louis XVIII; it was less handsome

but more practical in certain respects. It was published between 1821 and

again in 1829 in a print run of a thousand copies and consisted of

26 volumes of text and 11 volumes of folio plates.

Savant, Dominique Vivant Denon- After returning to France, many scholars and some soldiers, published accounts or travel journals concerning their stay in Egypt. There was a flurry of memoirs that dealt with military events but also included descriptions of daily life and the marvellous ancient ruins.

To this day, the best-known work, besides Description de l'Egypte, is the Voyage dans la Basse et la Haute Egypte [Travel in Low and High Egypt] by Denon, briefly mentioned who became the most famous person in the entire Napoleonic expedition. Dominique Vivant Denon (1747-1825) was a cultured man, a former diplomat and artist and traveller who managed to join the 'Oriental Expedition,' becoming a sort of correspondent. He was the first of the French scholars to travel through Egypt. In November 1798, he left Cairo and Joined General Desaix's, troops, who were about to pursue the Mamluk army and complete the military conquest. At 50 he proved to be more hardy than many of the soldiers, surviving the gruelling marches desert, a bout of ophthalmia and the torrid heat of Upper Egypt.

He was enthusiastic about Egyptian architecture and sculpture. He travelled on foot, horse or camel, drawing as went. On more than one occasion Devon's life was in danger, but he was fortunate and, thanks to the protection and cooperation of the army, always managed to achieve his ends. In December 1798, while travelling to Upper Egypt, Denon stopped for a short time at Hermopolis to see and draw the ruins of a temple (which no longer exists). In January of the following year, the French troops reached Dendera, where Denon was spellbound by the temple dedicated to the goddess Hathor. He wrote "I would have liked to draw all of it but I did not dare begin. Not being able to adapt myself to what I so admired, I realized I would only diminish the beauty of what I wanted to copy down. In no other place had I been surrounded by so many ruins able to stir my imagination. I thought I was, and in fact I really was, in the sanctuary of art and science. Upon seeing such an edifice, how many epochs my imagination conjured up! How many centuries it took a creative nation to achieve such results, at such a perfect and sublime level of artistic production!"

A few days later, Desaix's army, which was moving along the west bank of the Nile, spotted on the opposite shore the extensive ruins of a city: the legendary, ancient Thebes - something remarkable happened. As soon as they reached the ruins the French soldiers stopped and spontaneously began to applaud. "I did my first drawing," writes Denon, "as if I feared that Thebes would escape me. In order to draw another scene I found."

Denon continued his

search for monuments. With the army, he arrived at other localities,

including Edfu, Aswan and Philae. In February,

during his return trip, he was able to stop at Kom Ombo and return to Luxor

and Karnak Temple ("the most perfect and elegant

achievement of Egyptian architecture").

Denon continued his

search for monuments. With the army, he arrived at other localities,

including Edfu, Aswan and Philae. In February,

during his return trip, he was able to stop at Kom Ombo and return to Luxor

and Karnak Temple ("the most perfect and elegant

achievement of Egyptian architecture").

In July 1799, Denon went back to Cairo with over two hundred drawings that depicted everything: battles, monuments, towns, landscapes, ceremonies, animals, and various objects, and portraits of notables, artisans, and peasants. During a meeting at the Institut d'Egypte he read a report of his journey that excited the members. Napoleon himself examined his drawings and was so impressed that he immediately decided to promote two more expeditions to Upper Egypt. The following month, Denon left Egypt with Napoleon, Monge, and Berthollet and a few weeks later was back in Paris. After he had put his notes and drawings in order, in 1802 he published his Voyage dans la Basse et la Haute Egypte, in two volumes with 142 engravings, and was thus the 1st of the savants to publish.

Contact & Feedback : Egyptology and Archaeology through Images : Page last updated on 21-November-2025