Edward

William Lane

Edward

William Lane Few

Western students of the Arab world are as well known as the 19th-century

British scholar Edward William Lane (1801-76). During his long career, Lane

produced a number of highly influential works: An Account of the Manners and

Customs of the Modern Egyptians (1836), his translation of The Thousand and

One Nights (1839-41), Selections from the Kuran (1843), and the

Arabic-English Lexicon (1863-93). The Arabic-English Lexicon remains a

pre-eminent work of its kind, and Manners and Customs of the Modern

Egyptians is still a basic text for both Arab and Western students. Yet one

of Lane's most important works was never published. This was his book-length

manuscript, Description of Egypt.

Few

Western students of the Arab world are as well known as the 19th-century

British scholar Edward William Lane (1801-76). During his long career, Lane

produced a number of highly influential works: An Account of the Manners and

Customs of the Modern Egyptians (1836), his translation of The Thousand and

One Nights (1839-41), Selections from the Kuran (1843), and the

Arabic-English Lexicon (1863-93). The Arabic-English Lexicon remains a

pre-eminent work of its kind, and Manners and Customs of the Modern

Egyptians is still a basic text for both Arab and Western students. Yet one

of Lane's most important works was never published. This was his book-length

manuscript, Description of Egypt. At some point during his studies, Lane's interests took a highly original turn. Most people were fascinated by Egyptian antiquities, but Lane's primary attention moved from ancient to modern Egypt, and especially to Arabic, the language of the modern Egyptians. He also became intensely interested in their society, or to use the term current at the time, their manners and customs. It is unclear how he did so in spare hours in London during the 1820s, but he made substantial progress in Arabic-and not just classical Arabic but, even more remarkably, Egyptian colloquial Arabic as well. Yet Lane did not abandon his interest in ancient Egypt, leading to a duality of focus. Later, when he attempted to express his motives for going to Egypt in an early draft of Description of Egypt (reproduced here at the beginning of his Introduction), he had to rewrite the passage several times, finding it difficult to put the various elements into proper relationship.

Lane applied himself so assiduously to his Egyptian studies while still working as an engraver's apprentice that his health broke, rendering him susceptible to a life-threatening illness. He recovered but remained afflicted with severe chronic bronchitis for the rest of his life. Sometimes he could not walk down a London street without stopping and gasping for breath. Clearly he could not continue as an engraver, which required long hours of bending over a copper plate. It was equally clear that he needed a change of climate, both for his health and to fulfil his intellectual pursuits. On 18 July 1825, funded by a mysterious benefactor, Lane embarked for Egypt.

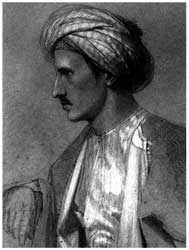

When Lane reached Cairo two weeks later he made good on his vow. Immediately he forsook Western clothing for Eastern attire, dressing in none other during the rest of his time in Egypt, for his purposes required not only that he gain an intimate knowledge of the details of Eastern society, including its material culture, but also that he not be readily recognized as a European. One should bear in mind, however, that the dress and resulting public persona that he chose were not those of a native Egyptian but of a member of Egypt's ruling Turkish elite. That facilitated his acceptance into Egyptian society and guaranteed him a degree of deference within it. Nor was Lane's commitment merely a matter of outward appearances, for he also furnished his house in Egyptian style, learned Egyptian table manners, and became perfect in Egyptian social usages. Within a year his Arabic was fluent. He developed a wide circle of Egyptian friends who knew him as Mansur, the name-and at least to some extent the identity-that he assumed in Egypt. The result fulfilled his expectations: "I was treated with respect and affability by all the natives . . . "

Lane's research in Cairo took two main thrusts. One was direct experience. This might be through everyday activities such as shopping, dealing with servants, or visiting friends and receiving guests-basic interactions that can teach a careful observer much. He learned practical details about Islam so he could enter Cairo's mosques, something a Westerner could not easily do in those days, and pray in them, which he did both individually and with the congregation, as the Description of Egypt explicitly states. He explored the monuments and quarters of Cairo, becoming proficient in the city's urban geography, a topic left vaguely in the background in Modern Egyptians, where the focus is on society. He also visited the archaeological sites around Cairo. The days he spent living in a tomb at the Pyramids of Giza he remembered as the happiest of his life.

Hence it is not surprising that Lane made many Egyptological mistakes, so many that it would be specious to annotate them all in his text. His king "Horus" (Horemheb), for example, certainly was not the immediate successor of Amenophis III, as Lane repeatedly asserts him to have been; but Lane could not have known that, so successfully had the record of the intervening Amarna period been erased. On the other hand, we see Lane at Tuna al-Gebel and Tell al-Amarna straining against the boundaries of current knowledge as he attempted to interpret the remaining, fragmentary evidence of Akhenaten's revolutionary innovations. Much the same could be said about his encounter with Hatshepsut, likewise unknown to him, whom he identified as a regent for Tuthmosis III and placed in the correct place in his list of kings (fig. 16o). In a note added at a later date, he accepted Wilkinson's identification of her as a Queen-Regent named "Amun-Neit-Gori." Of course, one of Lane's most important Egyptological contributions was to describe the condition of the monuments when he saw them; in some instances they were being destroyed before his very eyes.

Because Lane intended to write a book from the beginning, he kept a set of diaries and notebooks. The main body of these has survived, preserved in the Griffith Institute, where they have recently been catalogued. Some of the entries are little more than hasty notes about date, place, and temperature; others are highly detailed, so much so as to contain coherent textual passages that Lane was able to incorporate into his Description of Egypt manuscript with little revision.

1) population and revenue 2) civil administration 3) religion and laws

The first draft of Description of Egypt was a promising literary beginning, especially for someone not yet thirty years of age. Often it displays a strong, clear style; for example, the bridegroom passage, quoted above, is as good as anything Lane ever wrote. Other passages, as he was well aware, needed revision and development. Some of the sections with their various topics sat uneasily together, but Lane was still experimenting with placement and form. As notations in the draft show, it was intended to be the first of four projected volumes that would treat the whole of his Egyptian experience, each volume to contain approximately twenty-five illustrations. Placement points for the illustrations are indicated in the text, sometimes with a rough sketch drawn into the place, such as a preliminary sketch of the Alexandrian street scene (fig. S). Another interesting sketch shows a man peering into a cistern among the ruins of ancient Alexandria with Pompey's Pillar in the background, but it was not included in the final draft.

As promising as the first was, Lane was soon at work on a second draft of Description of Egypt, the composition of which may be tentatively dated to 1830. Now among the Lane Manuscripts in the Griffith Institute,' this draft marked a number of improvements over its predecessor as chapters became more focused and substantial, while the manuscript grew in several areas. The chapter on the Pyramids of Giza was extended to include all of the major monuments at that site as well as those of Saqqara and Dahshur. The draft closed after describing the desolate, almost obliterated ruins of Memphis with a reflective quotation from the prophet Jeremiah.

Another major area of expansion was the chapter about the history of Muhammad All, which grew approximately fourfold, approaching the large size it attained in the final draft. An impressive historiographical exercise, it drew primarily on al-Jabarti's manuscript history, which Lane had acquired in Egypt, and on Mix Mengin's published account of the pasha-though leaning toward the former work-in addition to Lane's own personal observations. It shows keen discernment of source material as Lane weighed evidence carefully before moving to judicious conclusions. For example, although he seems to have accepted the old canard about Ibrahim not being Muhammad All's son, Lane observed in a footnote that the pasha always referred to Ibrahim as being so, therefore displaying unease with the unfounded yet widely accepted story. Had it been published, this chapter would have been an important contribution to the history of modern Egypt; it also would have hastened the establishment of al-Jabarti's reputation in the West.

The area that grew the most, however, was the one dealing with the modern Egyptians. The three brief chapters about population, government, and religion and law were retained, while three new, relatively short, chapters were added about Egypt's Turkish elite and Christian and Jewish minorities. I But the most significant addition was a new chapter of some eighty manuscript pages entitled "Manners and Customs of the Moos'lim Egyptians." The need to keep the new chapter within somewhat proportionate limits clearly frustrated Lane, but his aim was "conciseness," and the chapter's function was subordinate to that of the work as a whole.

Lane submitted this second draft, along with a set of drawings, to the publishing firm of John Murray in early 1831. Then under the direction of the founder's son, John Murray II, Murray's had published Burckhardt, Belzoni, and many other distinguished writers about Egypt and the Middle East. Lane was aiming high. Murray handled Lane's manuscript in a highly professional manner by sending it out to a qualified reader, Henry Hart Milman, an accomplished scholar who had recently published a perceptive if controversial history of the Jews in which he interpreted them in their Semitic context. Milman's report strongly recommended publication: Lane's was, he said, "the best work which has been written on the subject." He expressed two minor reservations, the first being that the chapters dealing with the modern Egyptians ought to be removed: they were good, Milman thought, but should be the basis for an entirely separate book. Milman's second reservation concerned the scope of the work, for he thought it should be extended to cover Lane's travels in Upper Egypt and Nubia, as Lane indeed intended. Murray was highly pleased with both the manuscript and the report, as well as the illustrations-"the more the work contained of them, the better," Murray said-which he considered the most accurate he had ever seen. He agreed to publish the book. But he insisted on a new title and compelled Lane to write it on the spot. So Description of Egypt became:

Notes and views in Egypt and Nubia,

made during the years 1825, -26,-27, and -28:

Chiefly consisting of a series of descriptions and delineations

of the monuments, scenery, &c. of those countries;

The views, with few exceptions, made with the camera-lucida:

by Edwd Wm Lane

Lane returned to work with characteristic assiduity. Removing the modern Egyptians chapters was the work of a moment, doing little damage to the textual fabric of the rest of the manuscript. A much more formidable task was the composition of twenty-three new Upper Egyptian and Nubian chapters, plus a long supplement about the ancient Egyptians. The chapter on Thebes alone, by far the longest, accounted for about 50,000 words. He wrote this portion of Description of Egypt through at least two drafts, as his footnote references to a previous draft indicate. It is unfortunate that the preliminary draft has not come to light, for it contained additional material that Lane intended to publish. The structure of the Egyptian and Nubian chapters of Description of Egypt is even more emphatically the travelogue than the preceding ones. Yet it is a very contrived travel memoir, containing much more artistry than might first meet the eye. Lane compressed his two trips to Wadi Halfa and back into the narrative framework of one southward journey, ending with the preparation of his canjiah for the downstream journey: "The main-mast and yard were removed, and placed along the centre of the boat: one end resting on the roof of the cabin, and the other being lashed to the foremast. The tarankee't (or fore-sail) remained as usual."

Lane also revised the material that he had already composed. Most of these revisions were effective, resulting in memorable passages such as the description of his confusing initial experiences in Alexandria, his first impressions of Cairo, or the pleasure he took in his tomb-house at Giza. Yet some of the revisions are to be regretted, because he shortened then completely removed the Introduction that recounted his eventful voyage to Egypt. Then the beautiful passage ("I felt like an Eastern bridegroom ... ") that so memorably expressed his conflicting emotions as he prepared to set foot on Egypt for the first time was revised into a detached statement that diminished the personal element almost to the vanishing point: "I approached the beach with feelings of intense interest, though of too anxious a nature to be entirely pleasing ..." Several passing comments that expressed a vibrant, personal point of view were removed. The third draft, presented here, is naturally the most polished of the three, but the passages within it are not invariably the best that Lane wrote. Close study of the other two drafts, along with their associated manuscript materials, will richly repay further attention by researchers.

Without doubt one of Lane's largest tasks for Description of Egypt was preparing the illustrations for publication. The sheer number alone was imposing, for there were more than 150 of them, though some are missing from the manuscript and were already missing by the 1840s, when Lane's nephew, Reginald Stuart Poole, noted their absence in the margins. In pre-photographic days, reproduction of illustrative material was done by engraving, woodcutting, or the newly invented technique of lithography. Whatever medium was used-and Lane hoped to use all three-the artist's original work had to be copied anew, whether onto the engraver's metal plate, the woodcutter's block, or the lithographer's stone. Since Lane did not intend to do this himself, he needed to provide pictures as highly finished as possible to enable the appropriate craftsperson to realize his conception. This primarily required clarity of line in the case of the drawings destined to become woodcuts, where outline and contrast were paramount. But Lane hoped to have as many of them as possible rendered by metal engraving and lithography to achieve the delicacy of line and shading that those media, especially the latter, could convey. Hence the high artistic quality of many of Lane's sketches, with their delicate sepia shading and, in two instances, bright coloration.

The maps alone were a formidable undertaking, for Description of Egypt contains nine of them-thirteen if one counts each map section on the two plates that cover the Nile Valley from Giza to Wadi Halfa. The maps of the Delta and the Nile were based on W. M. Leake's Map of Egypt, which, despite numerous shortcomings, remained a standard through much of the nineteenth century.' Lane travelled along the Nile with a copy of Leake's map, from which he made the templates for his own. But Lane's maps were more than mere copies of Leake's, incorporating as they did his on-site adjustments and corrections. The same is true for the two maps of Cairo, the one of the city and its environs and the other, more detailed one of the interior of the city, which were both based upon maps in the French Description de l'Egypte. The most original of Lane's maps is the one of Thebes, the product of his extended stays at that site. It strikes a fine balance between detail and clarity that makes it an excellent reference tool for a book such as Lane's. In Lane's cartography for Description of Egypt we see yet another dimension of his talents that found no expression in his later published work.

The third draft of Description of Egypt constitutes a fair copy that would have delighted any Victorian typesetter. The wording was clear and the intent for note and figure placement unambiguous. His occasional, often inadvertent mistakes in spelling and grammar stood out sharply and would have been readily corrected. Only a few really rough edges remained, and he intended to smooth most of those away, such as an illustration annotation in chapter ten that was to be developed further, but never was. Temporary removal and subsequent misplacement was the likely fate of the missing appendix about the publications of the pasha's printing press at Bulaq. Inevitably, the close reader finds the occasional faulty detail, such as the omission of the letter J in the lettered series for the key to one of his views of Cairo, although a notch is there for it, and it apparently escaped his notice that he did not include the illustration for the face of the Third Pyramid at Giza. One will also observe that some of the notes to chapter twenty-six that Lane added after his second trip to Egypt are rougher than the others, but there can be no doubt that he would have worked them up to standard when the manuscript went to press, had the need arisen. One could go on; the fact remains that Lane's was an unusually clean manuscript. The finished work filled three volumes of text (removal of the modern Egyptians chapters reduced it from its initially projected four) and five volumes of illustrations. These constitute the third and final draft of Description of Egypt, the one presented in this edition, now housed in the British Library.

Lane submitted the revised draft to Murray, who again referred it to Milman, who in turn declared it even better than the previous one. But political conditions remained unsettled, so Murray continued to postpone publication. Although Lane agreed with the wisdom of this decision, he was frustrated by the delays, which, perhaps combined with unknown personal factors, threw him into a serious mental malaise. His thoughts returned increasingly to Egypt, where he had spent so many happy, creative moments. Letters to his friends became punctuated with expressions of longing to be there again. As he sank into depression, Description of Egypt came to his aid.

Lane returned to England in autumn 1835. He made some inquiries about the progress toward publishing Description of Egypt, but was met with evasion or silence by John Murray III, who was becoming increasingly active in the management of the firm. Lane probably should have been alarmed; instead, he considered this just another irritating delay. Soon he was deeply engaged in making the illustrations and correcting the proofs for Modern Egyptians. He assumed that the success of that work would precipitate immediate publication of Description of Egypt.

An Account of the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians was an instant success when it appeared in early December IS 36.1 The first printing sold out within two weeks; many others followed, as did several revised editions, culminating in the definitive fifth revised edition of 186o. Praised as "the most perfect picture of a people's life that has ever been written,"2 the influence of Modern Egyptians can scarcely be overstated. As Edward Said, a strong critic of Lane's, pointed out, Modern Egyptians made Lane "an authority whose use was an imperative for anyone writing or thinking about the Orient, not just about Egypt."' This remarkable book grew directly out of Description of Egypt.

It should not be assumed, however, that Modern Egyptians is a refinement of Description of Egypt or that it represents a maturation and reconsideration of Lane's research approach, in which he consciously turned away from the more diffuse effort that Description represented. Lane was still thoroughly committed to the publication of Description; the possibility that it might not be published at all had not yet occurred to him. Indeed, Description was likely the book that he cared about the most, having spent far more time and effort on it. Students of Lane's Modern Egyptians should pay close attention to Description of Egypt and its evolution, for it is the work that not only gave birth to Modern Egyptians but also defined the limits that the latter work assumed. There is little textual or pictorial overlap between the two. Had Lane known that Description would never be published, quite likely Modern Egyptians would have been different in shape and content.

Buoyed by the success of Modern Egyptians, Lane pressed John Murray III for immediate publication of Description of Egypt. Murray responded by withdrawing from the project and wishing him well with another publisher. How could such a thing have happened? The possible reasons are too complicated to set forth here in detail, but the fundamental problem lay in the passing of too much time. Big, illustrated travel books-as Lane's was probably if not entirely correctly perceived to be-had passed their heyday. Also, while Lane was in Egypt, Murray's had heavily committed itself to the publication of two books by Lane's friend and colleague, John Gardner Wilkinson: Topography of Thebes, and General View of Egypt and Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians (1837). Investment in the two books, especially the latter, had been heavy; Description of Egypt, also expensive to publish, would have competed with them. Murray's made a ruthless if unfair business decision. Lane was the loser thereby-as was the Victorian reading public.

The blow to Lane must have been devastating, even if softened by the success of Modern Egyptians. Efforts to place the work elsewhere came to naught. By the late 1830s a commercial publisher would have found Description of Egypt far too risky, while the alternative of private publication was beyond Lane's limited financial means. Lane did, however, twice try to salvage some parts of his work from the wreckage. The first attempt was a book about Thebes, based upon the Theban chapter of Description, which John Murray was considering, perhaps as a gesture of consolation. Lane set to work, completing a substantial portion of it. Although the manuscript has not surfaced, Lane jotted down a table of contents elsewhere, showing how the chapter's five sections would expand into a book of eleven chapters. Some of the later notes to the chapter, such as the references to Champollion's and Wilkinson's books, were probably added with the projected book in mind. This was also most likely the time when he added the two memoranda about inserting additional material from the supplement of Description. Lane's book about Thebes would have been a fine thing had it been realized, but when he was about one-third of the way through, he abandoned the project, explaining to Murray that he had no desire to compete with Wilkinson, whose two books covered much the same material, although Lane would have dealt with it much more fully than Wilkinson.

It especially pained Lane to see his illustrations lapse into oblivion; therefore he made another proposal to Murray for a volume of views of Egypt based upon the illustrations for Description with between loo to 150 woodcuts and a page or two of text to accompany each. "I think that it would be acceptable to a large class of persons, as illustrating many works on Egypt; especially Wilkinson's." A selection of the best of Lane's artwork from the Description would have made a magnificent volume, although the original works would have lost much in being translated from his delicate sepia washes into woodcuts. The preferable alternative of lithographing them all was probably too expensive to contemplate. A loose sheet inside Lane's copy of al-Jabarti's 'Aja'ib al-athar appears to be a preliminary estimate of the size and cost of such a work.2 On it Lane outlined a book somewhat larger than the one described in the letter to Murray, consisting of two volumes, one on the modern Egyptians and the other on "Scenery & Antiquities &c." It would contain as many as 215 woodcuts and six lithographic plates, although he also made a smaller estimate more in line with the size he had suggested to Murray. But nothing came of this idea either. By 1842, Lane had probably accepted the fact that he would never be able to publish his Description of Egypt or any significant portion of it.

Not that these were idle or unproductive years for Lane. His translation of the Arabian Nights appeared first in serialization and then in three volumes between 1838 and 1841. Though largely superseded now, Lane's reigned as the leading translation of the Arabic classic for much of the nineteenth century. Scholars still frequently consult its copious notes, much of the material for which Lane had gathered during his research for Description of Egypt. Lane's other major publication during this period was Selections from the Kuran (1843). But neither project was altogether satisfactory: the publisher for the Arabian Nights went bankrupt before paying Lane in full, while the Selections from the Kuran never received Lane's complete attention. Profound changes in Lane's personal life also occurred at about this time, such as the death of his mother and his marriage to Nefeeseh, whom he or a friend had purchased as a child in one of the slave markets of Cairo shortly before he left Egypt in 1828. Approaching midlife, Lane must have wondered what direction his career might take.

At this juncture Lane was approached by his friend Lord Prudhoe, later the 4th Duke of Northumberland. Their friendship dated from Lane's first trip to Egypt when he had been preparing Description of Egypt. Lord Prudhoe had long admired Lane's proficiency in Arabic; he had also realized from personal experience in the East the need for an authoritative Arabic-English lexicon. Now he offered to support Lane in the preparation of such a work. For Lane this was the realization of one of the youthful dreams that had impelled him to Egypt in the first place. He readily accepted Lord Prudhoe's offer and soon was preparing to return to Egypt for the necessary manuscript research and collection. His one reservation was extended separation from his sister Sophia Poole and her sons, to whom he was deeply attached. But once again Description of Egypt came to his aid. Lane made another proposal to John Murray: he would make the Description manuscript available to Sophia, who would select passages from it and recast them into a booklength series of letters ostensibly recording the impressions of an Englishwoman living in Egypt. The money from this, or at least the anticipation thereof, enabled Sophia and her family to go with Lane. In July 1842 Edward, Nefeeseh, Sophia, and Stanley and Stuart set sail on Lane's third trip to Egypt.

Lane's third trip to Egypt, 1842-49, was by far the longest of the three, but unlike the previous ones Lane travelled little during it and seldom went out into society. So enmeshed did he become in the lexicon project that he sometimes did not leave his house for months on end. Within the home, however, he was an affectionate family man, and he worked closely with Sophia, whose desk was within shouting distance of his, on her book. As planned, she selected passages from Description of Egypt, often after he had reread them and made changes in Arabic transliteration, punctuation, paragraphing, and like matters. Sometimes he updated the passages, as in the chapter about the Pyramids of Giza where Vyse and Lepsius had made important discoveries since Lane's work there.

In 1835, when Lane was preparing to leave Egypt, one of the sheikhs who was tutoring him in Arabic language and society took a piece of paper and wrote on it the shahada, or profession of faith: "There is no god but God and Muhammad is the messenger of God." He then tore it in two, giving one part to Lane and sticking the other into a crack in Lane's house. This was to guarantee that Lane would someday return to Egypt, for God would not allow the statement forever to remain divided. In the event, Lane did return seven years later, bringing his manuscript of Description of Egypt, when he began his lexicographical studies. But perhaps the sheikh's talisman was more effective than he imagined, for the Description of Egypt has now returned to Egypt, thereby realizing even more of the force of the sheikh's desire, for Description of Egypt embodies so much of Lane, his youthful experiences, and his high ideals. Essential to any full understanding of Lane's overall life and work, it is appropriate that his first book should after all these years return to Cairo for publication.

Having proceeded a little above the site of Eilethyia, the two lofty towers

of the pylon of the great temple of Apollinopolis Magna become visible.

About three hours after our first sight of these remarkable objects we arrived

before Ad'foo [Edfu], a village which occupies a part of the site of the City of

Apollo. I made a view of Ad'foo and its great temple from the opposite bank of

the Nile.'

Having proceeded a little above the site of Eilethyia, the two lofty towers

of the pylon of the great temple of Apollinopolis Magna become visible.

About three hours after our first sight of these remarkable objects we arrived

before Ad'foo [Edfu], a village which occupies a part of the site of the City of

Apollo. I made a view of Ad'foo and its great temple from the opposite bank of

the Nile.'The name of this place is commonly pronounced Ad'foo; but the literati of Egypt, for the sake of assimilating the incipient and final vowels, make it Ood'foo. The Coptic name was At'bo. It is a large village; the residence of a Ka'shif. It is situated at the distance of about a mile from the river, upon the front slope of a long and high ridge of mounds, the remains of Apollinopolis Magna. The village contains a mosque with a ma'd'neh; and extensive groves of palm-trees adjacent to it give it a pleasing appearance. The pylon of the great temple rises above it like a fortress. A part of the village is built upon the roof of this temple. There is also a second temple among the mounds, behind the village. At Ad'foo, the manufacture of pottery employs many families. There are a few Ckoobt [Coptic] families here; but above this place no Christians are found, excepting a very few at Aswan.

The great temple is situated at the north-western part of the village; and so crowded in front (that is, on the south), and also on the western side, by modern huts, that it is impossible to obtain a good view of it from either of these directions: but the modern huts are not the only objects which obstruct the view of this fine building; for it is, in some parts, buried nearly to the roof in rubbish. Though raised in the Ptolemaic period, when the arts of architecture and sculpture had much declined in Egypt, it is a very noble monument.

At a short distance from the south-western angle of the pylon of the great temple is another Ptolemaic temple [birth house], almost buried among the mounds of rubbish. This is a monument of Physcon; but the sculptures are partly by a later Ptolemy; supposed to be Lathyrus. It is a small edifice; consisting only of two chambers, and surrounded by a colonnade. High blocks (higher than they are wide) are interposed between the capitals and the architraves, and have a figure of the pigmy monster Typhon [Bes], carved in high relief, on each of their four sides. Hence the temple has been called the Typhonium of Ad'foo. Of the cornice, little remains. The sculptures on the interior face of the architraves in front are remarkable: two rows of figures are here represented meeting together in the centre: they are all armed with various instruments of destruction; and each procession commences by a human figure with the head of a lion. The interior of the temple is more than half filled with rubbish. We enter first a small apartment. The principal object in the sculptures is Horus, or Harpocrates, who is generally represented seated on the knees of his nurse Athor [Hathor], on the walls of the second chamber, which is longer than the first. This chamber contains a single column; opposite the entrance: there was probably another column behind it, corresponding in situation; but it has been thrown down; and the fragments are either buried in the rubbish or have been removed. On the left side-wall of the second chamber, Athor [Hathor] is represented seated on a throne, from which lotuses are springing out in every direction.

- Dendoo'r [Dendur], 21st May 1826

- The next district, or portion of the valley, above Ab'oo Ho'r is Wa'dee Dendoo'r [Dendur].

- On the western side (Ghur'b Dendoo'r) is a temple, of small dimensions, and of the same age as the main part of the great temple of Ckala'b'sheh; the reign of Augustus [30 BC-AD 14]. I landed before this temple early in the morning. It is situated almost close to the river; only a very narrow strip of cultivated land intervening; which, when I visited the spot, was covered with senna and the creeping colocynth.

- The temple is built on the irregular slope of the low, rocky ridge; which is here strewed with detached masses of stone, intermixed with broken pottery, indicating that a small town stood here. My view of this edifice, is taken from the direction in which it is seen in ascending the valley. It has, in front, a small portal; before which is a square enclosure, formed by well-built walls of stone. The front-wall of this enclosure has a singular peculiarity: its exterior face being slightly concave, or curved inwards.

- As the temple is unfinished, we may suppose that this enclosure was

to have been filled up, so as to form a platform: indeed it is partly so

filled. The portal is decorated with sculptures of the usual kind,

representing offerings; but with only a mystic name, similar to that

which I have mentioned in describing the great temple of Ckala'b'sheh;

so that it is uncertain when the sculptures were executed. The space

between this

portal and the temple itself is covered with fragments of stone; some of which formed parts of the temple, and perhaps of the two wings of a propylxum connected by the portal above mentioned. Among them I observed a small figure of a hawk; the head of which was broken off. - The portico of the temple has two small columns; between which is

the entrance. The front and the interior are sculptured, with the usual

subjects of offerings, and bear, throughout, the hieroglyphic name of

the Emperor Augustus (Autocrator Caesar). The exterior of the temple is

also similarly sculptured. The interior has been plastered and painted

by early Christians: but their work has almost entirely perished. Behind

the portico is a little chamber, without any sculpture, excepting round

the door through which we pass into the sanctuary. This is almost as

small as the former chamber, and, like it, without decoration, excepting

at the end, where is sculptured a shrine, in the form of a door, in

which is represented the king offering to Isis. A few feet behind the

temple, but not exactly in a direct line with the axis of the building,

is a small, square chamber, excavated in the rock. Before the door of

this was a little porch of masonry, which is now nearly demolished.