Napoleon enthused to the

Armee d'Orient “Soldats!

Du haute de ces Pyramides, 40

siècles nous contemplent".

Bonaparte intimately understood the significance of

the structures especially the administration and organization required to make

these magnificent tombs possible.

Pyramids are the visible apex of Egyptian burial

practices. Are knowledge is considerably more than Napoleon’s but we are

continuing to enhance our understanding of the environment that made them possible

and required. The physical structures are linked inextricably to the people’s ideology

and their belief that physical life was the preparation for their eternal

spiritual life.

Predynastic and early Dynastic

Established

tribes waned, probably because of climatic change, until c.6000 BCE with the

origins of settled communities. Climatic

change

had reduced habitable areas of the

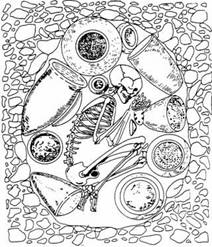

From the attention given to

the dead we can surmise their belief in the afterlife. Edwards (1991, p.20)

wrote that this eventually extended into two critical burial beliefs; that the

body most be preserved and the material needs, and that of the Ka, must be

provided for – these beliefs persisted for the whole of the Egyptian history.

Emery (1991, p.130) summarizes that “designs of the

tombs and funerary customs overlapped from one period to another, depending

largely on the locality of the burial and the inclination and social status of

the individual”.

The initial development in burial architecture was

the rectangular pit spanned by a wooden roof. The Abusir el-Melek cemetery, as

Adams & Ciałowicz (1997, p.19) explained,

demonstrate the evolving

styles; containing burials including oval graves, rectangle graves and deep

pits with sub-divided chambers, mud-plastered or mud-brick lined and with

wooden coffins (see Figure-2). Above this was a mound of sand, possibly with a

marker, which didn’t protect the burial from being exposed or robbed. The

mud-brick mastaba resolved these problems. The mastaba complex, which persisted

into the Middle Kingdom, had three elements: an excavated substructure, a mud-brick

superstructure and ancillary structures and enclosure walls.

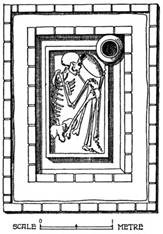

By the 1st

Dynasty the substructure was a pit subdivided into chambers,

the largest and

central chamber housed the body and was

covered with a wooden roof

after the burial. The mud-brick superstructure was niched (the “palace façade”)

brightly painted to mimic reed matwork, contained internal magazines and

possibly had a vaulted roof (similar to period coffins). The building was

surrounded by an enclosure wall and, in some 1st Dynasty royal

burials, servants were buried in structures outside the enclosure. The roof and

superstructure was built after the burial until Dewen’s (Den) reign, when a

staircase and portcullis were added - which surfaced beyond the mastabas edge

and allowed construction to be completed during the owners lifetime (see

Figure-3).

Other less common

developments were added; statues within a serdab, false doors, burial of solar

boats, the rock-cut chamber replacing pits and an early forerunner of the

royal-cult temple (mastaba of Qa’a). During the 2nd Dynasty some

mastaba incorporated a smooth exterior and two false-doors. Some tombs extended

false-doors into offering rooms, which later evolved into a chamber with

decorated panels and stelae.

The 3rd Dynasty

lasted less than 100 years and marked the beginning of a “classical era” of

monumental royal tombs. Non-royal mastabas continued to develop in complexity, materials

employed and size and were often clustered around royal tombs.

At least three step structures were built as royal

tombs, although only Djoser’s was completed. A number of small, sub 20m,

pyramids were constructed close to religious sites (from Seila to

Djoser’s step pyramid, or

step mastaba, at

A labyrinth of subterranean

corridors, some decorated with blue glazed tiles and stone representations of

logs and reeds, stretched nearly 4 miles and contained a huge central shaft.

Within the niched temenos (sacred enclosure) were many structures; some were

functional, as the north-facing royal-cult complex or the heb-sed court, and

others dummy buildings for the pharaoh’s afterlife activities.

It also contains a Southern

tomb with similar substructure as the pyramid but with a mastaba superstructure

- which could have been a cenotaph, canopic repository or a home for Djoser’s

Ka - this is an early form of a satellite pyramid.

The

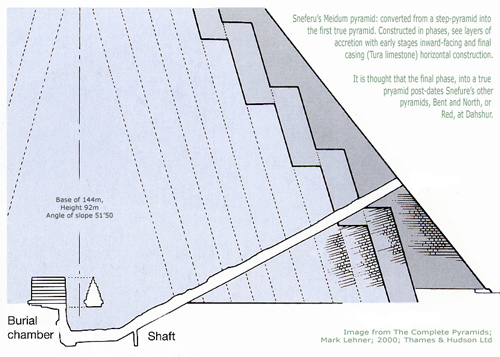

Sneferu can claim two,

probably three, distinct and innovative designs; Meidum, probably attributed to

Sneferu, is the transition from a step pyramid to a true pyramid. Its eight

internal step phases, as

The Bent pyramid was an “unsuccessful” building

because of the severe angle of its slope and, most significantly, the poor

geology of Dahshur (see Figure-5). It contained key elements of the fully

developed pyramid complex, including a southern satellite pyramid, and claims

the distinction of being the first true pyramid. Uniquely it had a second

passageway exiting on the western slope (Khufu’s pyramid at

The North or Red (local limestone is tinged red by

iron oxide) pyramid was the last of Sneferu’s buildings. It is simple and

elegant with a 43° slope - it is only shorter than Khufu’s by 15m – with a

centralized burial chamber. Some features are not present, such as a causeway,

but it serves as a perfect transition from Dahshur to

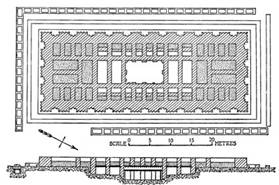

The Giza Plateau

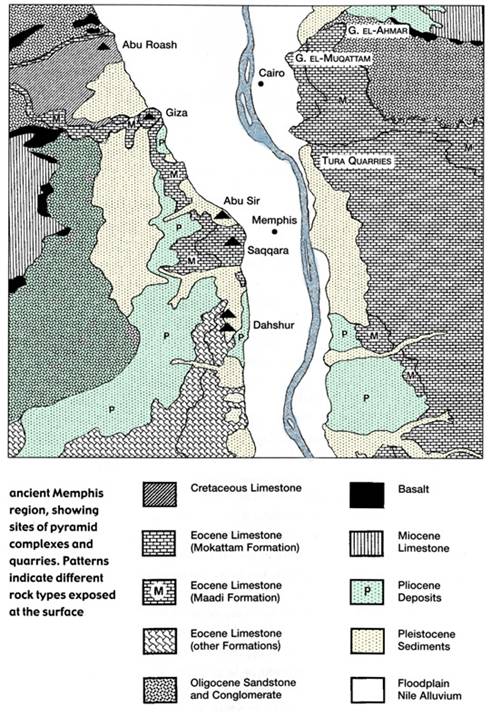

The plateau is formed from

horizontal strata of sedimentary limestone; it was an ideal site, with no

overburden to be removed and the natural bedding planes made quarrying easy. The

complex represents a colossal human achievement and is the pinnacle of pyramid construction.

The pyramids were built using precise measurements and accurate construction giving

a north-facing alignment. Non-royal burials are clustered and laid-out like an

organized town (see Figure-6).

Khufu continued to use

sedimentary Gypsum as a mortar to fill voids within the internal structure and

bond loosely fitting blocks. Corner blocks were of greater accuracy and

quality, which were equally important to the structural strength as the

foundations. Herodotus reported that the causeway was lined with fine relief

carvings.

The internal structure has

many new features with three burial chambers; the King’s chamber has five

stress-relieving chambers demonstrating an advanced understanding of

engineering. The Grand gallery, built with an extravagant corbelled structure,

is over 46m long and is an engineering master-piece. Efforts to prevent tomb

robbery failed and it was plundered during the

Djedefre, who included the

title “Son or Re”, reverted to the architecture of previous dynasties. Khafre

returned to the plateau utilizing a simple internal structure but with a large

and sophisticated royal-cult complex, including a large number of statues. The

complex included five elements; entrance hall, broad court, statue niche,

storage chambers and an inner sanctuary. The enigmatic sphinx and its unique two-sanctuary

temple are examples of the period’s innovation - there is an association with

the sun god and later Sun-Temples, and with the king as a “living image”.

Menkaure’s incomplete

pyramid was significantly smaller but compensated by using coloured stone to

emphasize the structure. It is probable that architects were aware that further

development could not be accommodated within the plateau; the primary route

from the plain to the plateau was blocked by the valley temple. The lower 16

courses were clad in

Abusir Pyramid Complex

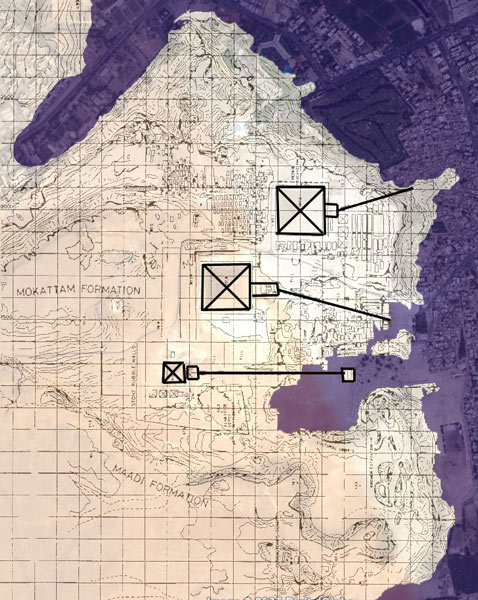

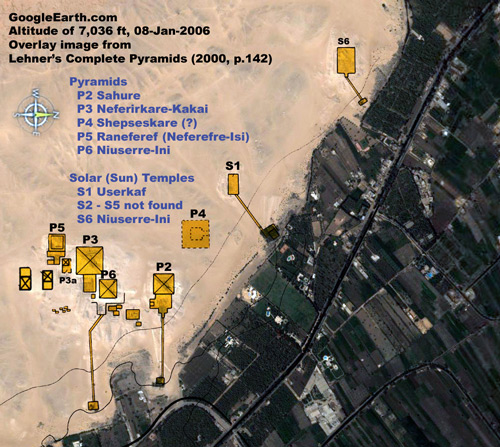

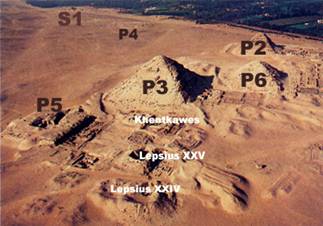

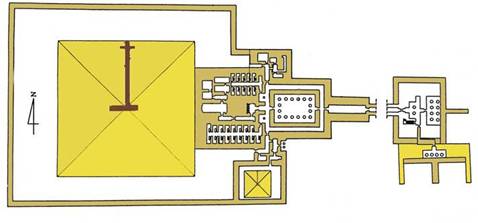

Abusir,

whose ancient name was Per-Usire or “Place of Osiris”, is the location of 5

pyramids from the 5th Dynasty and of two solar or sun-temples (see

Figure-7).

The complex is approximately 1.5km square and sits

on a sedimentary plateau. It

would have dominated the

Abusir demonstrates a

change in theological concepts and an increasing focus on the

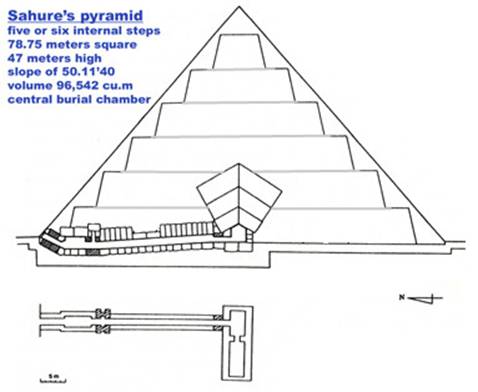

Pyramids are significantly

smaller than those of the great pyramids of Giza, for example Sahure’s pyramid

has a base of 78.75m and a slope of 50°11' compared to Khafre’s 215m and 53°10'

(Lehner 2000, p.17). Sahure’s complex, which stands on a 20 meter hill, is the

best preserved although once the casing was removed the construction techniques

allowed the buildings to deteriorate into mounds of rubble.

The use of stone non-indigenous

to Abusir was limited to key architectural features. Siliotti (1997, p.95)

wrote “the funerary temple seems to have gained in importance and is usually

quite large, built with expensive materials and decorated with exquisite

bas-reliefs, most of which have unfortunately been lost”.

The construction technique

was to form a level a base (possibly constructed from limestone blocks), into

which a pit was excavated. A number of inward leaning layers were built from low-quality

limestone blocks, quarried to the west of the complex, with voids filled with

mud mortar. A construction gap was left on the north side, allowing builders to

work on the burial chamber in parallel, which was later filled with debris.

Tura limestone was used for the outer casing. Neferirkare’s pyramid had an

unfinished girdle of masonry with a red-granite casing and it is thought

Neferirkare originally built a step pyramid and later changed it to be smooth

sided.

Internal chambers were accessed

from the north side via a pavement level passageway lined with red-granite and

protected with granite portcullis. Later in the period, certainly for Niuserre,

a north chapel was added giving access to the passageway. The limestone clad antechamber

and burial chamber had a three-layered gabled roof with huge 90-ton limestone

beams (see Figure-9) and to the east a serdab. A fragment of basalt sarcophagus

was found in Sahure’s chamber and red-granite in Neferefre’s. An interesting

observation on Sahure’s pyramid, reported by Verner (1997, p.284), is that “the

southeast corner is off by about 1.58m … and is not entirely square”.

We can determine, from

unfinished pyramids such as Neferefre, that construction of the tomb occurred

first, then the royal-cult complex and finally the valley temple and causeway.

The surviving

structures have a similarity and Sahure’s can be used to describe the repeated

features.

Each part of a King’s complex was named, for example Sahure’s

were:

|

Complex |

Sahure’s soul shines |

|

Pyramid |

The Rising of the Ba spirit

|

|

|

The Soul of Sahure Comes Forth in Glory |

|

Palace |

Sahure’s splendor soars up to heaven |

|

Sun-Temple |

Sahure’s offering Field or Field of Re (Sekhet Re) |

|

Prenomen |

He

who is Close to Re

|

The pyramids of Sahure and Niuserre

and the sun-temples of Userkaf and Niuserre have valley temples

connected to the

royal-cult complex by a causeway.

Neferirkare completed his valley

temple and the causeway’s foundations but Niuserre completed the works joining the

causeway to his own pyramid.

The valley temple was entered via a ramp that led

to a portico or covered ambulatory. The roof was decorated with gold painted stars

on a blue background and the ceiling was supported by granite palm fond columns

(Niuserre used papyrus bundles). The floor was of black

igneous basalt,

the dado of red-granite and above a layer of Tura limestone – which was

decorated with polychrome bas-relief, for example depicting the king in the

form of a Sphinx trampling enemies. A hall with two pillars led to the

causeway.

The causeway traversed

uneven ground - to keep the processional way at a constant incline from the

valley to the plateau significant buttresses were employed. The 2m wide corridor

was illuminated from small openings in the roof and its length was decorated

“including scenes of gods leading prisoners taken from

The royal-cult temple joined

the pyramid’s east side and was significantly larger than predecessors and is the

prototype of subsequent temples. The walls and columns were heavily decorated

with reliefs with a variety of subjects such as hunting, fishing, fowling,

soldiers, sea-voyages, courtiers, victories over traditional enemies, offering

bearers and the King’s insignia. In Khentkawes II’s temple square pillars, painted

red and inscribed with her name and titles, were used.

Niuserre added to Neferefre’s

(who is also known as Raneferef) royal-cult temple after the ephemeral ruler’s

death. Part of the temple held the first hypostyle hall; its roof was supported

by 20 wooden columns in four rows. Uniquely a ‘Sanctuary of the Knife’ was

added for ritual slaughter of animals – this has a possible association with sun-temples.

Deep within the temple is

an offering chapel with a false door, statue of the king and an offering basin.

A sophisticated drainage system ran throughout the temple using channels, copper

drains and water spouts. Neferirkare’s temple was finished quickly using

mud-brick and wooden columns; this indicates that Neferirkare died before it

was finished and Niuserre completed the work.

During this period the

temple was laterally ‘divided’ into outer and inner elements by an internal

traverse-hall and the external enclosure wall. The outer part included an

entrance hall, an open court with a colonnade (palm columns) and altar; the

inner rooms included magazines, five-niche chapel, an alabaster floored offering

hall or sanctuary and a satellite pyramid that simulated the main tomb.

Niuserre also included a statue of a recumbent lion and a square antechamber

with a central pillar supporting its roof.

Entrances led into the

pyramid enclosure and Neferirkare’s held two large boat burials. Niuserre

introduced two huge blocks of masonry on the east side of the complex flanking

the royal-cult temple and joining the enclosure wall. Lehner (2000, p.142) says

these are “precursors of the great pylons at the front of later Egyptian

temples”.

Outside

of the complexes were other burials, although the number is considerably less

than at

Abusir

Sun-Temples

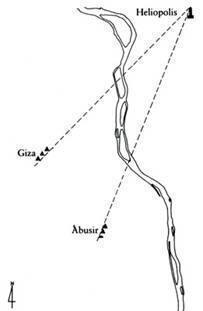

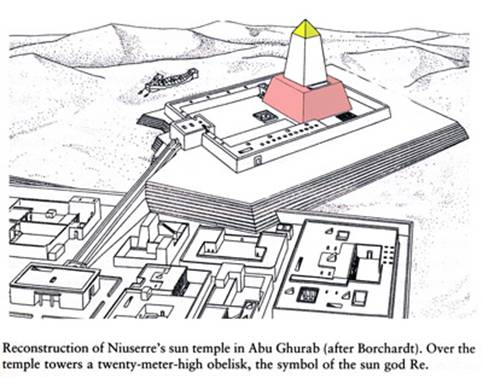

Userkaf was the first to build a sun-temple at Abu Gurob (an extension

of Abusir) about 3 kilometers north of his

The

Abusir Papyri and other documents record the existence of six temples although

only those of Userkaf and Niuserre have been discovered. It is possible that

only two temples existed and that each successor re-built and re-named

Userkaf’s temple, before Niuserre built his own. However, there are indications

that Sahure’s sun-temple could have been over-built by Niuserre’s pyramid

complex. Additionally Ty’s tomb at

Schaeffer

& Borchardt excavated at Abusir in 1898-01 and Riche in 1955-7 determining

that the temples were built in phases and Userkaf’s was added to by Neferirkare

and more extensively re-developed by Niuserre. Userkaf’s temple was called

Nekhen-Re (Stronghold of Re) which was also the name of the pre-dynastic

capital Hierakonpolis, the primeval sanctuary of the Horus falcon. The sun-temple’s

focus was a blunt Obelisk which stood on a step pyramid of limestone with a red-granite

casing similar to

Menkaure’s

pyramid at ![]() )

hieroglyph. Both sun-temples

are of similar construction

and are have the characteristics of a pyramid complex; with a “pyramid”, valley

temple, causeway, upper temple, enclosure and, in Niuserre’s case, a huge

mud-brick boat. Inside Niuserre’s upper temple were fine reliefs including Sed-Festival

scenes and in the Chamber of the Seasons depictions of the Akhet, Peret and

Shemu seasons.

)

hieroglyph. Both sun-temples

are of similar construction

and are have the characteristics of a pyramid complex; with a “pyramid”, valley

temple, causeway, upper temple, enclosure and, in Niuserre’s case, a huge

mud-brick boat. Inside Niuserre’s upper temple were fine reliefs including Sed-Festival

scenes and in the Chamber of the Seasons depictions of the Akhet, Peret and

Shemu seasons.

One of the three sets of Abusir Papyri lists daily

offerings brought from temple to pyramid - it is difficult to resolve the

purpose of sun-temples but they were clearly an important part of the ritual

offering to the gods and to the king’s cult. Why their development stopped is

equally unclear.

End of Monumental building

Menkauhor’s missing pyramid it is known to be the

first 5th dynasty king to migrate to Saqqara, a custom that

continued throughout the

The significant

differentiator is the Pyramid Texts, which is found in each of the burial

chambers, including some queens. These spells, prayers and hymns (nearly one

thousand are now known and they significantly pre-date the Dynasty) use magic

to guarantee the king’s rebirth and were carved into limestone and filled with

blue paste. No burial chamber makes use of all of the utterances, which

includes the Cannibal text.

The south-wall of

Unas’ sarcophagus chamber has a resuscitation text with utterances 213–222

containing vital texts. These include ‘you have not gone away dead; you have

gone away alive’ and the assurance that ‘your name will live on among living people

even as your name comes to be with the gods’.

These powerful

assurances of immortality are the extant conclusion to thousands of years of

refinement – reaching back to shallow pit-graves scratched into the arid soil. Monolithic

monumental building, combined with a sophisticated religious ideology, all

strived to achieve an eternal spiritual life described within the phrases

carved so resoundingly and confidently into Unas’ pyramid.

Appendix and Images

|

Figure-1.1

Brunton (1937), 1.2 author

|

|

Figure-2.1 Emery (1991, p.138), 2.2 author

|

|

Figure-3 Emery (1991, p.72) - 1st Dynasty

Mastaba.

|

|

Figure-4 Lehner (2000, p.97)

|

|

Figure-5 Sampsell (2003)

|

|

Figure-6

GoogleEarth

|

|

Figure-7:

Abusir complex

|

|

Siliotti (1997, p.95). Abusir, northerly aspect

|

|

Figure-8: Verner (1997; p.303 & 271)

|

|

Figure-9,

Based on Verner (1997, p.285 & 286)

|

Bibliography

|

A. Rosalie David |

1988 |

Ancient

|

Equinox ( |

|

Aidan Dobson & Dyan Hilton |

2004 |

Complete

Royal families |

Thames & Hudson |

|

Aidan Dodson |

2000 |

Monarchs

of the |

The |

|

Alberto Siliotti |

1997 |

The

Pyramids |

Weidenfeld & Nicolson |

|

Barbera Adams & Krzysztof Ciałowicz |

1997 |

Protodynastic

|

Shire Publications |

|

Barry J Kemp |

2006 |

Ancient

|

Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group |

|

Bonnie Sampsell |

2003 |

Traveler's

Guide to the Geology of |

|

|

Bruton |

1937 |

Predynastic

burial from El-Amra |

|

|

Christiane Ziegler & Jean-Luc Bovot |

2001 |

Art

et archéologie: l’Égypte ancienne |

Ecole du Louvre |

|

Colin Renfrew &

Paul Bahn |

2004 |

Archaeology:

Theory, Methods and Practice |

Thames & Hudson |

|

Cyril Aldred |

1974 |

Egypt

to the end of the Old Kingdom |

Thames & Hudson |

|

Cyril Aldred |

1987 |

The Egyptians |

Thames & Hudson |

|

Dieter |

1991 |

Building

in |

|

|

Dieter |

2003 |

Encyclopaedia

of Ancient Egyptian Architecture |

I B Taurus |

|

Donald Redford

(Editor) |

2001 |

|

|

|

George Reisner |

1934 |

History

of the Egyptian Mastaba |

Imprimerie De L’Institut Français D’Archéologie Orientale |

|

George Reisner |

1942 |

History

of the |

|

|

George Reisner |

1955 |

History

of the |

|

|

George Reisner |

1931 |

Mycerinus,

|

|

|

I E S Edwards |

1991 |

Pyramids

of |

Pelican Books |

|

Ian Shaw |

2002 |

|

|

|

Ian Shaw &

Paul Nicholson |

1995 |

Dictionary

of Ancient |

The |

|

Ian Shaw &

Robert Jameson

(Editors) |

2002 |

Dictionary

of Archaeology |

Blackwell Publishers |

|

Lorna Oakes |

2003 |

Sacred

sites of Ancient Egypt |

Anness Publishing |

|

Mark Lehner |

2000 |

Complete

Pyramids |

Thames & Hudson |

|

Miroslav Verner |

1997 |

The

Pyramids |

Atlantic Books Ltd |

|

Naguib Kanawati |

2001 |

Tomb

and Beyond, burial customs of Egyptian officials |

Aris & Phillips |

|

no author listed |

1999 |

Egyptian

Art in the age of the Pyramids |

Metropolitan |

|

Philip Watson |

1987 |

Egyptian

Pyramids and Mastaba Tombs |

Shire Publications |

|

R. David |

1998 |

Handbook

to Life in Ancient |

|

|

Rosalie David |

2002 |

Religion

and Magic in Ancient |

Penguin Books |

|

Salima Ikram |

2003 |

Death

and Burial in Ancient |

Pearson Education |

|

W B Emery |

1991 |

Archaic

|

Penguin Books |

|

Wolfram Grajetzki |

2003 |

Burial

Customs in Ancient |

Gerald Duckworth |

|

Journals and Periodicals |

|

KMT, Volume 15

Number

2, Summer 2004 |

|

Egyptian Archaeology, Bulletin of the EES

Number 26, Spring 2005 |

|

|

|

The Ostracon,

Volume 11 Number 3, Autumn 2000 |

|

|

|

Internet Sources |

|

Ancient Egypt Web Site; author |

|

Biography of Ludwig Borchardt;

|

|

Development of the Royal Mortuary Complex;

Dr. Zahi Hawass

https://guardians.net/hawass/mortuary1.htm |

|

Excavation report:

Architectural remains at Abusir-south;

|

|

https://www.gizapyramids.org/code/emuseum.asp |

|

Guardian’s Abu Sir, The Pyramid of Sahure;

Andrew

Bayuk |

|

King Sahure and a |

|

Osiris.Net; The Tomb of Ty; Thierry Benderitter |

|

Pyramid of Sahure;

Su

Bayfield

https://www.egyptsites.co.uk/lower/pyramids/abusir/sahure.html |

|

Pyramid Complex of Sahure

at Abusir; Association of Egyptian

Travel Businesses |