The Egyptian Temple

Introduction

“Words spoken by Amun-Re, King of the gods to his son User-Ma’at-Re Mery-Amun; ‘Your temple shall exist like heaven, my majesty being within it and being exalted … I will establish my image in it eternally as long as the land exists’” – Ramesses-III’s mortuary-temple (El-Sabban, 2000, p.60). Egyptian temples are magnificent structures, simultaneously the “civilization’s finest achievement” and institutions that dominated the people’s very existence (Baines,-1997,-p.216). Temple development reached its zenith during the New-Kingdom and was the locus of the people’s relationship with the gods and universe. The contract inscribed into a temple’s walls was their rational and existential belief.

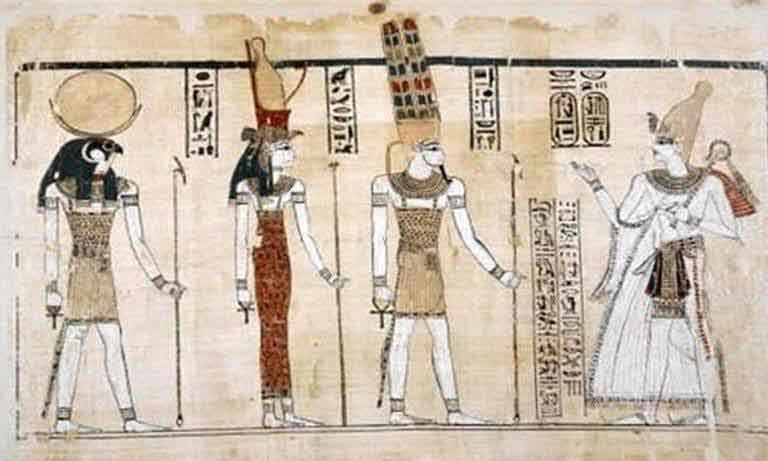

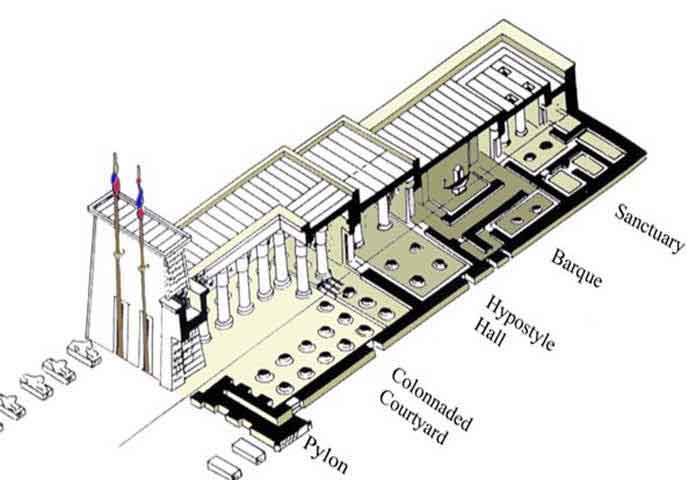

Tobin (2001,-p.362) explained that the universe, or cosmos, was articulated by metaphysical creation-myths. Different aspects of the creation-myths evolved (such as the Heliopolitan-cosmology, Hermopolis-cosmology, and Memphite-cosmology) and, during this period, the Theban-cosmology was predominant (Wilkinson,-2000a,-p.76). So to understand the function of temples we must first understand the creation-myths. Wilkinson (2000a,-p.76/7) wrote that creation-myths relate to the beginning of time when a mound of earth rose from the ubiquitous primeval-waters. A bird rested on reeds growing on the mound which became a sacred place. Everything was simultaneously defined at this ‘first moment’ and nothing was by chance - the regular rhythm of day-night, seasons, the rise-and-fall of the Nile was established. The temple mimics the ‘first moment’ with the ceiling representing the heavens, the floor modelled the mound, and columns represented the reeds, lotus, and papyrus [Fig.-1]. Every part of the temple’s physical structure had a role in symbolizing some aspect of the origins or function of the cosmos and that cosmic-structure, cosmic-function, and cosmic-regeneration reoccurs throughout temple symbolism. The gods are inseparable from the mound, for example (David,-1998,-p.121) Amun begot himself, coming from an egg, on the mound. Some temples were designed so that their outer courtyards and hypostyle hall would submerge during the inundation, by Nun, presenting a powerful and cyclical re-enactment of the mound-of-creation rising from the primordial-waters [Fig.-2].

O’Connor (2001,-p.199-201) articulated that each temple’s form symbolizes the cosmos’s eternal cycle of decline and re-birth and that (Hart,-2001,-p.116) the primary function of temples was to control the inimical forces of chaos within the cosmos and to maintain Ma’at (harmony, balance, and equilibrium of the entire cosmos which was embodied within the Goddess Ma’at including Truth, Justice and Morality). Each temple is a microcosm of the universe and a representation of the mound-of-creation, but also a coffin for the sun-god to rest within and be re-born within each day (David, 1998,-p.128). David (1981,-p.5 and 2002,-p.198/9) continued that temples were “houses of the gods” and did not serve as places of communal worship; its servants (the Priests) were not ‘pastors’ and there were no congregations. The King, who held the full knowledge of the gods and was “seemingly divine in character and abilities” (O’Connor,-2004,-p.145) was the High Priest of all temples (Oaks,-2003,-p.154), and guarantor of the universe’s balance (Sauneron, 2000,-p.29) and Egypt’s position within the divinely-created universe.

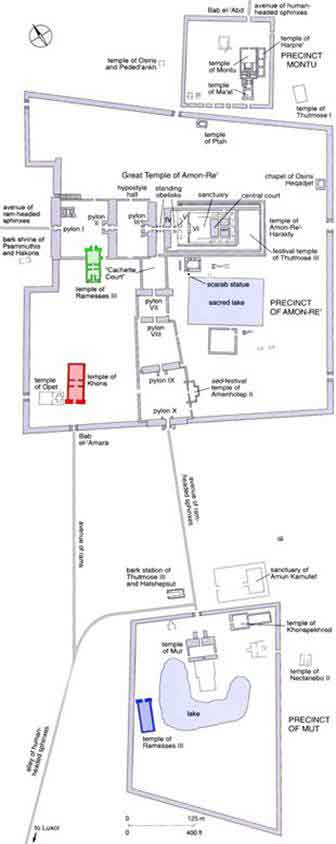

Gundlach (2001,-p.362/3) estimated that thousands of temples existed; possibly all conurbations had a temple to house the gods, although very few are extant - especially in the Delta (Johnson,-2004,-p.65). Gundlach determined that temples bridged the religious and the secular worlds; their impact on a region’s administration and economy was extensive and each temple was essentially an extension of the State, or King, and was a political institution as well as a communication mechanism with the gods.

Form and Function of the Temple

The form and function of the temple has many influences and purposes; many only partially understood and, as Haeny (2005,-p.123) explained, the thinking behind Egyptian creations is often elusive. The New-Kingdom was a period of extensive building activity and many temples were dedicated to the Theban triad of Amun, Khonsu, and Mut (Strudwick, 1999,-p.45) [Fig.-3.1/2]. Hornung reported (1982,-p.223) that every deity is associated with a fixed ‘home’ and that the important god and the capital city are associated - which during the New-Kingdom was Thebes or the “city of Amun”.

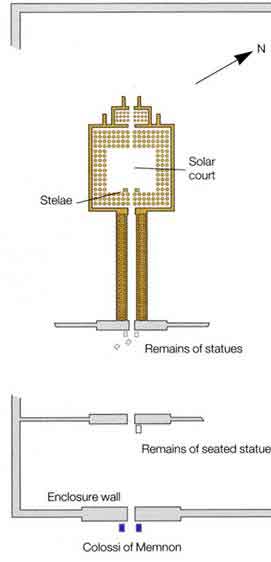

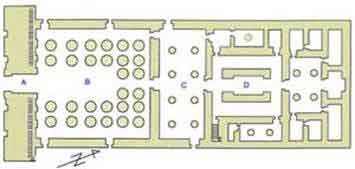

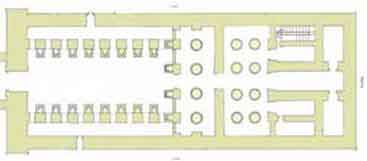

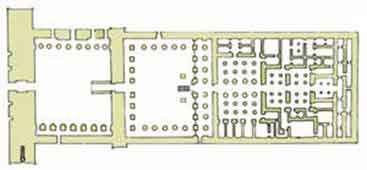

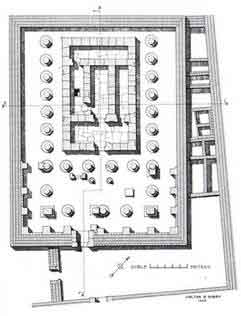

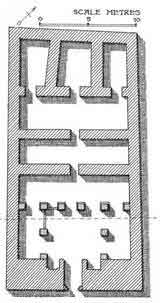

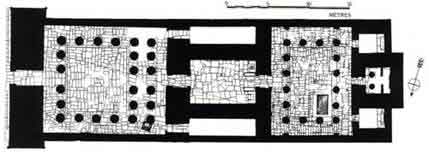

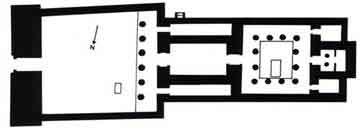

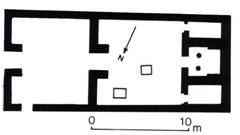

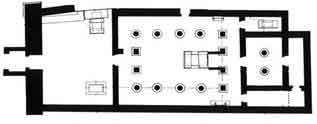

Both Snape (1996,-p.29) and Badawy (1990,-p.255) agreed that the Temple-of-Khonsucan be regarded as a typical New-Kingdom cultus-temple [Fig.-4]. Although innovation in design was both unnecessary and undesirable (David,-1998,-p.128), Snape (1996,-p.8) also explained that no New-Kingdom temples are identical and also that none are completely unique – I demonstrate this within Fig.-5 where four temples built for Ramesses-III each have a similar-but-different design. I support this with the two temples at Buhen [Fig.-6], located at the southern extremity of Upper-Egypt, which are significantly simpler that those at Thebes - lacking a pylon, courtyard and additional buildings but retaining the essential Sanctuary, Vestibule and Hypostyle Hall. Arnold (2003,-p.40) described the Buhen temples as an example of ambulatory temples. Woolley/Randall-MacIver (1911,-p.83) suggested that the Ahmose temple had a mud-brick vaulted roof in the local style of Nubian dwellings, as well as brick walls. I suggest that these temples have more in common with the majority of temples built during the New-Kingdom than those at Thebes; also that local resources, conditions, and habits dictated the building style employed.

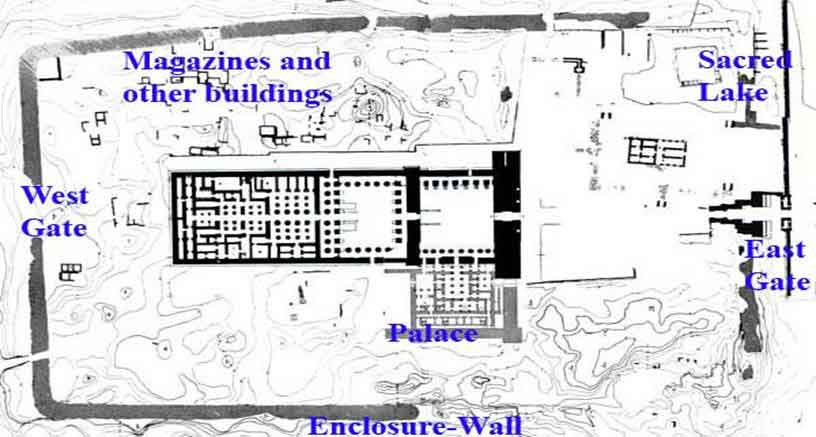

Finding a suitable location for a temple was not only a matter of location and orientation; factors included the temples purpose and whether compromises were needed to facilitate earlier structures – for example Medinet Habu enclosed the Amun-Temple built by Hatshepsut/Thutmosis-III which was the “traditional burial place of Amon” (Johnson,-2004,-p.66/7).

Egypt can be compared to a gigantic compass - with the Nile bisecting north-south and the solar path east-west (Badawy,-1968,-p.183). New-Kingdom mortuary-temples, for example, were oriented to the diurnal-cycle of the setting-sun so that the most sacred part is facing westward (Gundlach,-2001,-p.368) but in reality being perpendicular to the Nile was convenient for connecting temples to the Nile with canals, as was Medinet Habu.

Temples could be classified into broad types; disagreement regarding the classification continues (Haeny,-2005,-p.87). David (2002,-p.186) simplified the classification into cultus-temples (east-bank of Thebes), where the resident god was worshiped, and mortuary-temples (often in the “land of the dead” on the west-bank of Thebes (Johnson,-2004,-p.66)), where the resident god along with the deified ruler (also during their life-time (Leblanc,-1997,-p.49)) was worshiped. Wilkinson (2000a,-p.25) considered that the division is false, but writes that Egyptians used ‘mansion-of-the-god’ (cultus-temple) and ‘mansion-of-a-million-years’ (mortuary-temple) to differentiate temples.

The ‘standard’ temple’s design was influenced by noble/royal house-architecture (David,-1998,-p.128/9) of this period and also influenced some tombs. Martin (1993,-p.39) articulated that at Memphis, during the reign of Tutankhamun, a new type of funerary-monument was built – the ‘temple tomb’ – which mimics the style of smaller purpose-built mortuary-temples [Fig.-7].

Murray (1931,-p.2) and Snape (1996,-p.29) differed slightly about the elements of a ‘standard temple’ but we can identify the Sanctuary or Shrine, Hypostyle Hall, Vestibule (passage or room between outer and interior building), Courtyard and Pylon. Each element was either open-to-the-air or roofed (David,-1988,-p.84) depending on its sanctity. Beyond the temple, within the temenos, could be a number of other buildings which were surrounded by an enclosure-wall, and finally were the temple holdings which spanned the country.

Beyond the Enclosure-Wall

Temples had extensive land-holdings which, in a cash-less economy (David,-1978,-p.6), provided produce for offerings of "all the beautiful … things through which a god lives" (Gasse,-2001,-p.434) and sustaining its dependants. Gasse (2001,-p.434) expressed that Ramesses-III’s Amun temple at Thebes (Harris Papyrus, regnal year 32) owned 240,000 hectares (593,000 acres) of land and (Breasted,-1906,-p.97) owned 86,486 people – this is extensive especially as Ramesses’s first priority may have been supporting his mortuary-temple at Medinet-Habu (which was completed regnal year 12 (Breasted,-1906,-p.3)). Estates were not contiguous; Sety-I controlled large tracts beyond the second cataract (Wilkinson,-2000a,-p.75), and included farmland, marshes, mines/quarries, vineyards, towns, and slaves – each proving for the fabric and sustenance of ‘their’ temple.

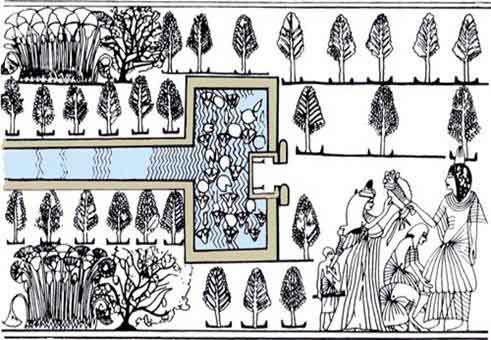

Blyth (2006,-p.64) stressed the importance of the temple garden saying that “no temple would have existed without a garden.” The Harris Papyrus lists 433 gardens in Thebes alone (Breasted,-1906,-p.97). Temples, as Blyth continued, were beautified not only with precious metals but with flowers, trees, and pools [Fig.-8.1]. It was very necessary for gardens to provide the flowers required for Festivals, such as the 270 fresh-flowers, bouquets and baskets for the Festival-of-Opet recorded on the southern-wall at Medinet-Habu (El-Sabban,-2000,-p.101).

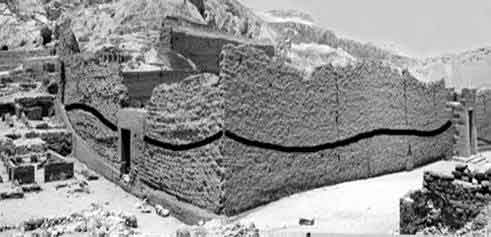

Enclosure-Wallsusually enclosed the sacred area and had a single entrance into the temple-domain. The walls were undecorated but white-washed (Hölscher,-1951,-p.5) and had alternating concave and convex mud-brick walls which represented the waters of Nun and the primeval-ocean (Shafer,-2005,-p.5) [Fig.-8.2]. More practically it also gave seclusion and physical-protection – Medinet-Habu, with its military-focus (Arnold,-1996,-p.150), had fortifications and gates built into the enclosure-wall and it was here that local inhabitants took refuge during times of trouble (Wilkinson,-2000a,-p.194).

Standard Temple

Temples were built along the central-axis (Arnold,-1996,-p.150) with a rectangular design often constructed from stone (Shafer,-2005,-p.4/5); sanctity increased further into the structure culminating with the Sanctuary – which was the focus of the temple and where the god lived within a cult-statue (David,-1988,-p.98). Each contiguous element, closer to the sanctuary, has a higher elevation and a lower roof with decreased illumination and increased sanctity [Fig.-4.1] and decreased levels of chaos (Gundlach,-2001,-p.368).

Between each part of the temple were doorways which provided practical protection from searing heat, controlled light entering the sacred areas, and also acted as symbolic thresholds - many were made of wood and, for some temples, were covered in electrum and copper (Breasted,-1906,-p.113). Some were individually named (Wilkinson,-2000a,-p.67) and Bell (2005,-p.134) says that the sanctuary doors were called the “doors of heaven”.

Temenos

The open-space between the temple and the enclosure-wall contained a range of buildings, many secular in function and, as Pinch (2002,-p.21) wrote, the temple was like a town with their own granary, workshop, offices, school, slaughter-house, hall-of-record (library), magazines, wells, and housing. Some of the many possible religious structures included:

Crio-Sphinxes protected the processional-way, or causeway; for example between the Temple-of-Khonsu and Luxor (Badawy,-1968,-p.255).

A T-shaped Quay (Hölscher,-1951,-p.11)connected Medinet-Habu, via a Canal, to the Nile (Arnold,-2003,-p.183). It served as the major entrance to the temple, especially for processions (Wilkinson,-2000a,-p.54) and Hölscher (1951,-p.11) considered that it co-dated the temple and facilitated the moving of building materials [Fig.-8.1].

![]() Obelisks,

such as the two red-granite examples given by Ramesses-II to Luxor [Fig.-8.3],

fronted Pylons and were given (only by Kings

(Wilkinson,-2000a,-p.57))

to temples to commemorate major events in a reign; such as the coronation, victories or simply in self-praise (Habachi,-1998,-p.95).

The Obelisk’s pyramidion caught the first and last rays of the sun and it’s metal-covering of gold or electron

(gold/silver amalgam) would beam the sun’s powerful-rays throughout the locality. Lichtheim (1976,-p.46)

translated Amenhotep-III’s text from two obelisks placed at Karnak to say “… my father

rises between them.”

Obelisks,

such as the two red-granite examples given by Ramesses-II to Luxor [Fig.-8.3],

fronted Pylons and were given (only by Kings

(Wilkinson,-2000a,-p.57))

to temples to commemorate major events in a reign; such as the coronation, victories or simply in self-praise (Habachi,-1998,-p.95).

The Obelisk’s pyramidion caught the first and last rays of the sun and it’s metal-covering of gold or electron

(gold/silver amalgam) would beam the sun’s powerful-rays throughout the locality. Lichtheim (1976,-p.46)

translated Amenhotep-III’s text from two obelisks placed at Karnak to say “… my father

rises between them.”

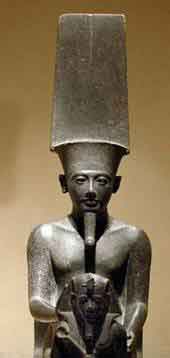

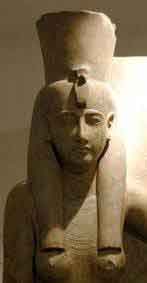

Statues, such as the six colossi fronting Luxor (Habachi,-1998,-p.94), [Fig.-8.3] acted in a protective role but also demonstrated the relationship between king and gods (Wilkinson,-2000a,-p.59).

The Sacred Lake [Fig.-8.4]provided water, from the water-table, for the purification of priests and symbolically represented the primordial-ocean and renewal as the sun rose over it each day (Wilkinson,-2000a,-p.72).

Pylonsare consistently built as two massive trapezoid/tapering towers linked by a cornice topped gateway [Fig.-![]() 8.4]

and were used for sun rituals (Shaw/Nicholson,-2002,-p.232).

They

represented the horizon (Gundlach,-2001,-p.374)

or the sun-rise between two mountains (Arnold,-2003,-p.183)

and Shafer (2005,-p.5) also speculated that it represented a vagina with connotations

of re-birth.

8.4]

and were used for sun rituals (Shaw/Nicholson,-2002,-p.232).

They

represented the horizon (Gundlach,-2001,-p.374)

or the sun-rise between two mountains (Arnold,-2003,-p.183)

and Shafer (2005,-p.5) also speculated that it represented a vagina with connotations

of re-birth.

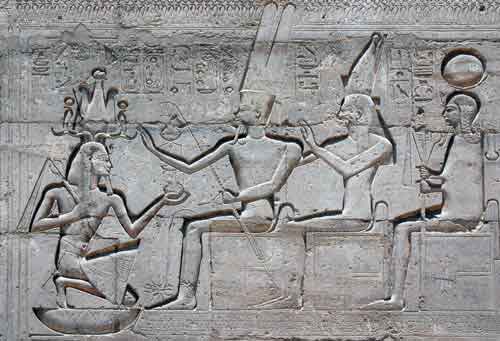

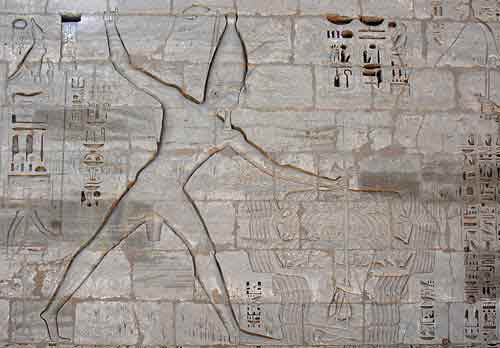

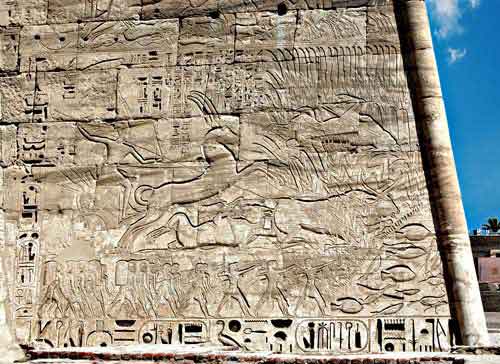

Pylon’s were extensively decorated with scenes depicting destruction rituals which bound the pylon into the symbolism of maintaining world-order and resisting chaos [Fig.-8.6]; such as the King smiting/sacrificing foreigners to his father Amun-Re, offering bound captives to Gods who empowered the King by offering weapons, and hunting scenes (Arnold,-2003,-p.183). Pylon’s were apotropaic, protected by images such as the anthropomorphic representation of the sisters Isis and Nephthys (associated with the South and North (Shaw/Nicholson,-2002,-p.232)), and the king. Gigantic images on both sides of the structure of the King publicly demonstrate his dominion over foreign rulers (representing peoples from the South/West and the North/East) (Hölscher,-1951,-p.5).

The Temple-of-Khonsu [Fig.-4.1] has recesses for four flag-staffs, although the Temple-of-Ramesses-III at Karnak has none. Arnaudiès(2004,-p.23) shows that a staff from Horemheb’s Ninth Pylon at Karnak rested on an inscribed copper base-plate. Shawn/Nicholson (2002,-p.232) explained that the flag/pendant represents the hieroglyph for ‘God’ and Edgerton/Wilson (1936,-p.116/7) recorded 16 flag-staff dedications at Medinet-Habu where Ramesses, as “Horus, mighty bull”, dedicated the cedar-wood staffs to his father Amun-Re.

The Courtyardis usually (Wilkinson,-2000a,-p.62) a Peristyle

court, with a colonnade, that transitioned between ![]() the sacred and the more public areas. The Temple-of-Ramesses-III

[Fig.-8.7] has eight Oriside statues of Ramesses on each flank (Phillips,-2002,-p.140)

wearing either the Red-Crown or White-Crown (Badawy,-1968,-p.242)

representing Upper-Egypt (Southern-Egypt) or Lower-Egypt (Northern-Egypt) (Shaw/Nicholson,-2002,-p.75).

By using this simple representation it becomes “insignificant from the cultic standpoint” whether the temple is

physically oriented to the cardinal direction or not (Gandlach,-2001,-p.369)

- the distinction between south and north is a re-occurring theme within the entire temple.

the sacred and the more public areas. The Temple-of-Ramesses-III

[Fig.-8.7] has eight Oriside statues of Ramesses on each flank (Phillips,-2002,-p.140)

wearing either the Red-Crown or White-Crown (Badawy,-1968,-p.242)

representing Upper-Egypt (Southern-Egypt) or Lower-Egypt (Northern-Egypt) (Shaw/Nicholson,-2002,-p.75).

By using this simple representation it becomes “insignificant from the cultic standpoint” whether the temple is

physically oriented to the cardinal direction or not (Gandlach,-2001,-p.369)

- the distinction between south and north is a re-occurring theme within the entire temple.

Some temples, such as the Temple-of-Khonsu [Fig.-4.1], had a portico or colonnade at the rear of the Courtyard with one or two rows of columns/pillars and partially enclosed with a screen wall; Badawy (1968,-p.179) explains that this is the beginning of the temple proper.

The Courtyard contained royals and non-royal statues and stela (Gundlach,-2001,-p.374). Wilkinson (2000a,-p.62/4) doesn’t think the statues were Ka hosts but more probably that they were a memorial and encouraged visitors support to the deceased’s eternity by pronouncing their name, they also magically participated in the ‘revision of offerings’. As the courtyard became packed with statues they were not discarded but buried within caches or pits (Luxor and Karnak Courtyards held significant caches of magnificent statues).

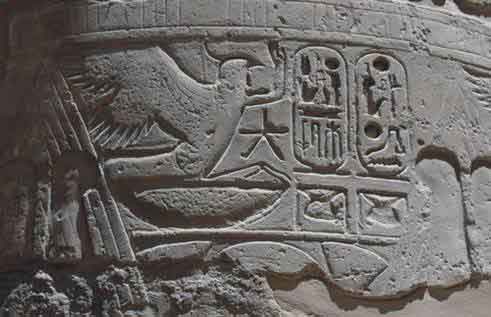

![]() David (1998,-p.133)

confirmed that ordinary people had little direct contact with the temple, at most watching processions or praying within

its Courtyard or Hypostyle Hall. Blyth (2006,-p.59) said that the hieroglyph

combination of the lapwing/basket/star into the Rekhyt hieroglyph-group (Gardner G24/V30/N14) indicates that privileged

people had access to an area and Wilkinson (2000b,-p.87) translated the

hieroglyph-group as “All the people give praise” and explained that it is often praising the King’s cartouche [Fig.-8.9].

David (1998,-p.133)

confirmed that ordinary people had little direct contact with the temple, at most watching processions or praying within

its Courtyard or Hypostyle Hall. Blyth (2006,-p.59) said that the hieroglyph

combination of the lapwing/basket/star into the Rekhyt hieroglyph-group (Gardner G24/V30/N14) indicates that privileged

people had access to an area and Wilkinson (2000b,-p.87) translated the

hieroglyph-group as “All the people give praise” and explained that it is often praising the King’s cartouche [Fig.-8.9].

Wilkinson says that the Rekhyt hieroglyph-group could represent the captured people of Lower-Egypt or a symbol of kingship – we might therefore expect to find them in other more sacred locations. A second hieroglyph-group, of pa’et, indicated a more elite mythological people who could originally have been members of the royal family (Bell,-2005,-p.164) [Fig.-8.10].

The people’s faith in the power of the temple and its gods is demonstrated by the endless grooves made in its exterior-walls where scrapings were taken for personal devotional use (Wilkinson, 2000a, p.99) (Fig.-8.8).

The Hypostyle Halltraverses the width of the temple and a regular feature is its columns – those flanking the processional-way have open-papyriform columns, where other columns were bud-papyriform (Badawy,-1968,-p.179). Their practical purpose was to support the roof but they symbolically represented the lush and plentiful vegetation on the mound-of-creation (David,-1998,-p.128) - the symbolism of the sky supported by the columns over the earth are vivid and ancient text proudly reports that “its pillars reach heaven” (Wilkinson,-2000a,-p.65/7).

The Barque-chamber(Wilkinson,-2000a,-p.69/70) held the god’s portable sacred-barque [Fig.-8.11 and Fig.-8.12].

The Sanctuaryis the most sacred part of all temples and its function was to house the image within which the god rested. The image was usually contained within a smaller box-like feature, Naos, which could be portable (Wilkinson,-2000a,-p.69).

It is the most elevated part of the temple and has the lowest roof, the highest floor, and the least illumination (Strudwick,-1999,-p.47). This is a representation of the mound-of-creation where the God rested during the ‘first moment’ of the universe’s creation and was the sacred-centre of the temple and the point of transition between this existence and the next (Gundlach,-1998,-p.364). It was submerged in deep-gloom or near-total darkness with only an occasional ray-of-light falling through an opening in the roof above the cult-statue (Michalowski,-1969,-p.13).

Haeny (2005, -p.111) said that the double false-doors of Sety-I, Ramesses-II, and Ramesses-III were located at the centre of their mortuary-temple’s barque-chamber and it allowed the deceased King’s spirit to enter and leave the temple. This bond between form-and-function dates to the Old-Kingdom and, in some cases, worked in conjunction with chapels of the ‘hearing ear’ which were located outside of the temple (Wilkinson,-2000a,-p.71).

Inscriptionsare carved on every available level of temples’ walls. The two-dimensional scenes and inscriptions are a characteristic element of New-Kingdom temples (Gundlach,-2001,-p.374).

The exterior, visible to the uninitiated, focused on bombastic accounts demonstrating the Kings right-to-rule and his supportive-association with the Gods. Hölscher (1951,-p.5) explained that inscribed-scenes simultaneously war-like and religious; recording symbolic victories of the god’s son using the power given to him by Amun to conquer all before him. Not all exterior-scenes were martial; Ramesses’ Temple in the Precinct of Amun has three decrees recording donations of temple-furniture (Nelson,-1936,-p.232). Badawy (1968,-p.179) continued that courtyard walls-space was extensively utilized for en-creux (inset) or bas-relief (raised) painted inscriptions. Because the courtyard was used by the populace the inscriptions did not describe divine-mysteries but focused on boastful military sagas, festivals, foundation ceremonies, and praising the gods.

Exterior inscriptions were never merely decorative but were also intended to interact with the people. Documents in common use, such as the Harris Papyrus, are written in hieratic (British Museum), and hieroglyphs were unlikely to be understood by the greater population. I suggest that they were presented orally, even to music, during festivals by priests to the populous as an effective bonding between the people and the King – but whilst maintaining the mystery of god’s words.

The sacred elements of the temple typically held scenes of Kingly humility and reverence to the Gods (Fig.-10). For example the ‘Treasury’ has extensive lists of the riches that Ramesses makes to the Gods to demonstrate his gratitude and to retain the support of the Gods who offer the gift of Jubilees in return (Breasted,-1906,-p.15/17).

Medinet-Habu (Fig.-9), predominantly based on Ramesses-II’s mortuary-temple (Hölscher,-1929,-p.37), is well preserved and has extensive inscriptions:

Inscriptions (Breasted,-1906,-p.10) record a 3,000 person expedition to Silsileh to quarry - although Johnson (2004, p.73/4) said that Amenhotep’s mortuary-temple was extensively ‘mined’ for Ramesses-III’s Temple-of-Khonsu and I suggest that because Medinet-Habu is only 750m distant it may have also provided material for Ramesses’s workers. This indicates a certain lack of respect for previous ruler’s mortuary-temples - Johnson claimed that every statue in Medinet-Habu was usurped from Amenhotep-III.

The fully-preserved southern-wall is inscribed with a Calendar which was mainly a copy of a calendar from Ramesses-II’s mortuary-temple (El-Sabban, 2000, p.60) – although Lurson (2005,-p.107) suggested that Ramesses may have been inspired by his father’s (Sety-I) mortuary-temple. The rear and northern walls are extensively concerned with war; inscribed from the rear and moving forward representing significant conflicts in regnal years 5, 8 and 11/12 (Breasted,-1906,-p.4).

Other broad-groupings of inscriptions (Breasted,-1906,-p.19/87):

Blessings of the Gods and offerings to them

King’s goodness, power, valour, and heroism

People’s praise of the King and triumphant audiences

Wretched chiefs of foreign lands and their overthrow

Egypt’s security provided by the King’s military prowess and might

Processions/festivals

Sed ceremonies, ancestor lists, and foundation rituals

Festivalswere a vital component of life during the New-Kingdom, bringing together all levels of society (www.philae.nu). During the two-day Beautiful-Feast-of-the-Valley Festival (El-Shabban,-2000,-p.67/8) Amun’s statue was carried within a sacred-barque in procession from Karnak to the western-bank (Spalinger,-2003,-p.126). The procession visited Deir El-Bahri and the mortuary-temples (Bell,-2006,-p.136), resting overnight before returning to Karnak. By the 19th Dynasty Mut and Khonsu also joined the procession (Strudwick,-1999,-p.78) which occurred during Smw (second month of summer) during the full-moon (Haeny,-2005,-p.136). Some individuals might be permitted to receive an Oracle during the procession where a judgement/question was resolved by god - Hatshepsut employed an Oracle to demonstrate her legitimacy as ruler (Gundlach,-2001,-p.373).

During the Old-Kingdom the Festival was focused on Hathor but by the New-Kingdom Amun, as the State God, had assumed the role (Bell,-2006,-p.137). This supports the flexibility and practicality within the Egyptian rational that was applied to the Gods.

The Beautiful-Feast-of-the-Valley was a celebration of the reunion and rejuvenation of the deceased and family-ancestors, maintaining their continued eternal-lives (www.philae.nu) – it was a time of great feasting and revelling by the participants who celebrated with “with the greatest zeal and devotion” (Herodotus).

The sacred-barque mimicked a boat, in the same way that the sun god traversed the celestial sea by boat, but was carried out of the temple in procession on the shoulders of priests (Wilkinson,-2000a,-p.70). Way-stations were built along processional routes which allowed the portable sacred-barque to temporarily rest on an altar - allowing the god, and ‘porters’, to be refreshed during the procession [Fig.-8.5]. Amun crossed the Nile in the river-boat Userhat (Kemp,-2006,-p.249) ‘Powerful Prow’ - the Harris Papyrus (Breasted,-1906,-p.120) proudly extols a 224-foot cedar construction, with ram’s heads front-and-rear with uraeus-serpents wearing Atef-crowns, and shining with gold and gem-stones to the water-line.

Conclusion

It would be gratuitous to attempt to describe every characteristics and symbolism of New-Kingdom temples.

However, I can imagine…

the sacred-barque arrives at the necropolis, carried with reverence on priests shoulders to the accompaniment of melodic rhythmic chanting, musical-pulses played on sistrums and tambourines, supported by the female temple chantresses (such as Asru, who’s remains are within the Manchester Museum) and the wailing of the on-lookers who are intoxicated by the presence of the living-god, the Triad of Gods, and beer.

The methodical procession, led by the King, approaches Medinet-Habu entering through its mighty Pylon and Courtyard. The procession, leaving the throng of followers behind, passes into the Hypostyle Hall (Fig.-8.13/8.17) through huge golden-doors that glided-open revealing inward facing inscriptions of the king and protected overhead by she-of-Nekhbet, Re, and the King’s cartouches (Fig.-8.15). The huge columns sprouting like papyrus on the mound-of-creation (Fig.-8.14) and with vivid polychromic decorations, stretching to the dimly visible ceiling decorated like the blue-black night-sky with bright stars of the gods gleaming as if at a distance. Twists of incense-smoke curl slowly, lit by stark beams of light from clerestory windows, filling the temple with the perfume of Punt.

The party sways up the ramps into the cool and calming atmosphere of the cramped barque-chamber where the sacred-barque is rested on a plinth (Fig.-8.16).

All-but-a-few withdraw. User-Ma’at-Re Mery-Amun, the son of Amun, reveals the statue that god resides within inside the sacred-barque. After ensuring everything is prefect the small group of devotees advance towards the Naos. The statue is glided into its cabinet, which is carefully secured; to rest within the sanctuary until tomorrow’s procession returns to Karnak. They withdraw, removing foot-prints, content and relieved that Ma’at has been preserved – silently closing the doors they leave the diminutive chamber in celestial darkness.

Nothing is simple, static, or commonly explainable within the rational of an Egyptian temple. The Cosmos perpetually balanced on a knife-edge between cosmic decline-and-regeneration - every temple represented the universe and played-a-part in controlling the inimical forces of chaos within the cosmos and (with the required human assistance) maintained Ma’at. From King-to-Fellaheen this complex belief gave the people a rational for their existence and a single-minded purpose for their being.