Manetho and

the modern chronology of ancient Egypt

Manetho and

the modern chronology of ancient EgyptThe basis of the modern chronology of ancient Egypt rests on several literary sources. The most important of is the writings

of Manetho (Ma-Net-Ho). He was an Egyptian priest (305-285 BC) who lived during the reigns of Ptolemy I and Ptolemy II and

was employed at the Temple of Sebennytos in the Delta. He had knowledge of Egyptian hieroglyphs

and Greek and, as a priest, access to original source material including ancient records and king lists. He would also have

been able to draw on his own personal experience of religious beliefs and practices, and the rituals and festivals. He is

credited with eight works; his most important, the Aegyptiaca (History of Egypt), was written in the

reign of Ptolemy II

In this book, he compiled a chronicle of the Egyptian kings from 3100 BC down to 343 BC. Written in Greek and based on

the original lists which the priests help in temples. This book remained the authentic source for Egypt's history for several

centuries until it was lost, probably during the fire of the library of Alexandria (c.390 AD).

He began his history with the commencement of Dynasty 1, c.3100 BC, and the accession of Menes, the first king to rule

a united Egypt. He divided the history into thirty dynasties and a later chronographer added a 31st dynasty which included

three Persian kings who ruled Egypt as part of their empire. Currently, this whole period is known as the 'Dynastic', 'Pharaonic'

or 'Historic Period', and Egyptologists retain Manetho's division of Egyptian history into this sequence of dynasties. However,

there is no clear understanding of the exact definition of what a 'dynasty' meant in Manetho's terms: sometimes, a dynasty

included rulers who were related to each other by family links, or sometimes the dynasty changed if there were no direct

successors or another family group seized the throne. However, in other instances, one family seems to span more than one

dynasty, with no indication that the changeover had occurred because there was any violence or conflict.

Manetho's account provides estimates of the lengths of reigns, and he also includes popular stories about the rulers,

obviously drawing on informal information that came to his attention, as well as the official records. If this history had

survived intact, it would constitute the best extant chronological source for ancient Egypt, since it was clearly based

on the author's first-hand experience of the ancient records. However, no complete version of Manetho's work has yet been

found, and it is only preserved in edited extracts in the writings of the Jewish historian, Flavius Josephus (c.70 AD),

whose work was still being used in the Renaissance as a basic source for studying ancient Egypt; and in an abridged form

in the works of the Christian chronographers, Sextus Julius Africanus (c.220 AD), Eusebius (c.320 AD) and George the Monk,

known as Syncellus (c.800 AD).

The versions provided by Eusebius and Africanus do not always give the same lengths for kings' reigns, and Manetho's

own chronology of the reigns, and the years he gives for each reign, are not always confirmed by other sources. Sometimes,

instead of providing details of individual reigns, only the total number of rulers is given, and the names of some kings

appear in distorted forms which do not correspond to the writing of the names given in other inscriptions. Again, there

is no corroborative evidence from other sources for some of the anecdotes.

Manetho’s history also had a strong influence on biblical studies. His long chronological history provided a potential

anchor point around which dates for biblical events could be established, particularly with regard to the chronology of

the Exodus from Egypt under Moses and the chronology of civilization after the flood in Noah’s time. In fact, Josephus’s

identification of the Exodus with Manetho’s account of the expulsion of the Hyksos kings at the start of what would have

been the 18th Dynasty, deeply influenced centuries of biblical scholarship. Chronology in the nations outside of Egypt,

particularly in Canaan and Mesopotamia, depended upon chronological links to events inside of Egypt - Manetho was an early

influence on our development of chronology in those other nations as well.

In some instances, it has been possible to use information from excavations and other historical texts to confirm or

refute Manetho's statements. Perhaps the most obvious example concerns the Pre-dynastic Period, the era prior to c.3100

BC, when Manetho listed the gods and demi-gods as the rulers of Egypt before human kings came to power. However, the excavations

of Flinders Petrie and others have shown that pre-dynastic cultures (c.5000-3100 BC) did actually exist, and that, at first,

local chieftains and then the kings of the two kingdoms in the north and south ruled the country during this period when

the foundation was laid for the social, religious, artistic and technological developments which later influenced the Dynastic

Period.

Jean

Francois Champollion's decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs in the early nineteenth century was crucial to our modern understanding

of the chronology of Egypt. His work was based first on deciphering the names of various Egyptian rulers, and subsequently,

on using Manetho's list of kings to clarify the position of each of these kings within the chronological sequence; then,

he was able to confirm that his identification of the ruler was correct. Despite its limitations and problems, Manetho's

chronology remains the basis of the current, accepted sequence of rulers and dynasties. However, it was Champollion's initial

discovery and subsequent work which revolutionised the study of Egyptian history by enabling scholars to read the ancient

texts. This provided Egyptologists with access to knowledge about Egyptian chronology and the order of reigns which was

preserved in several inscriptions known as the 'king lists'. Two of these lists - the

Turin Royal Canon of Kings and the Palermo Stone - were respectively

inscribed on a papyrus and a stela, while the others - the Table of Abydos, the Table of Karnak, and the Table of Saqqara

- occurred on temple or tomb walls.

Jean

Francois Champollion's decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs in the early nineteenth century was crucial to our modern understanding

of the chronology of Egypt. His work was based first on deciphering the names of various Egyptian rulers, and subsequently,

on using Manetho's list of kings to clarify the position of each of these kings within the chronological sequence; then,

he was able to confirm that his identification of the ruler was correct. Despite its limitations and problems, Manetho's

chronology remains the basis of the current, accepted sequence of rulers and dynasties. However, it was Champollion's initial

discovery and subsequent work which revolutionised the study of Egyptian history by enabling scholars to read the ancient

texts. This provided Egyptologists with access to knowledge about Egyptian chronology and the order of reigns which was

preserved in several inscriptions known as the 'king lists'. Two of these lists - the

Turin Royal Canon of Kings and the Palermo Stone - were respectively

inscribed on a papyrus and a stela, while the others - the Table of Abydos, the Table of Karnak, and the Table of Saqqara

- occurred on temple or tomb walls.

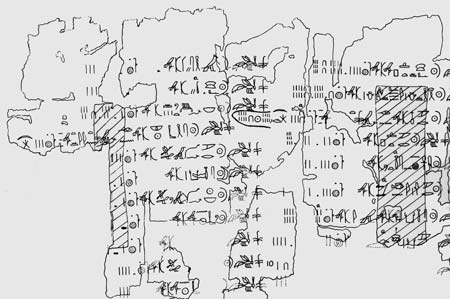

The Turin Royal Canon is a list of kings written in hieratic on a papyrus which dates to the reign of Ramesses II (1290-1224

BC). It contains some information which is also found in Manetho, giving the name of Menes as the first king of Egypt, and

listing the gods and demi-gods as the rulers of the Pre-dynastic Period. It supplies the complete years of each king's reign

and any additional months and days, but since only fragments of the papyrus have survived, only 80-90 of the total of royal

names are preserved.

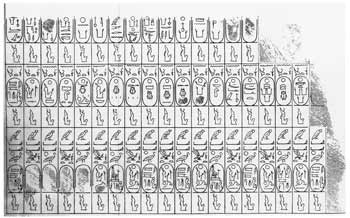

The

Palermo Stone is a slab of diorite, and the main fragment is housed at Palermo; other, incomplete fragments which probably

came from the same stone are in the Cairo Museum. Originally, the stone would have been an upright, free-standing stela

which was probably set up in a temple. Inscribed on both sides with horizontal registers, each divided vertically into compartments

filled with hieroglyphic texts. These inscriptions provide a continuous, year-by-year record of the events of the reigns

of the first five dynasties, from Menes down to the 5th Dynasty. They record the outstanding event of each year, including

military victories, construction of temples, festivals and mining expeditions.

The

Palermo Stone is a slab of diorite, and the main fragment is housed at Palermo; other, incomplete fragments which probably

came from the same stone are in the Cairo Museum. Originally, the stone would have been an upright, free-standing stela

which was probably set up in a temple. Inscribed on both sides with horizontal registers, each divided vertically into compartments

filled with hieroglyphic texts. These inscriptions provide a continuous, year-by-year record of the events of the reigns

of the first five dynasties, from Menes down to the 5th Dynasty. They record the outstanding event of each year, including

military victories, construction of temples, festivals and mining expeditions.

Some of the king lists were inscribed on the interior walls of the temples, so that the previous kings of Egypt (whose

spirits were believed to be present in their names on the list) could receive spiritual sustenance from the rituals and

offerings made in the temples. In return, it was thought that they would approve and accept the ruling king as the legitimate

overlord of Egypt. In the Abydos List, inscribed on a wall in the Gallery of the Lists in the Temple of Sety I (1309-1291

BC) at Abydos, figures of King Sety and his son Ramesses II are shown in the accompanying scene, making offerings to 76

previous rulers who are represented by their names which are enclosed in cartouches.

The Karnak List occurs on one of the walls in the Temple of Karnak at Thebes. It dates to the reign of Tuthmosis III (1490-1436

BC), and originally included the names of 61 kings, but when it was discovered in 1825 AD, only 48 names were still legible.

The list gives the names of some kings not mentioned in other lists, but it does not provide an accurate sequence of their

names. Finally, the Table of Saqqara, found at Saqqara on a wall in the tomb of Tjuneroy, an overseer of works, included

the names of 57 previous rulers whom Ramesses II had selected to receive worship, but only 50 of these are now visible because

the wall has been damaged.

Therefore, although the king lists are a very important chronological source, there are limitations in using them as

accurate historical records. Essentially, they were placed in the temples or tombs to play a part in the rituals and offerings,

and were never intended to be historical records. It was not therefore necessary for them to be complete; for, while evidently

they included only the names of rulers from Menes down to the king in whose reign the list was prepared, they also excluded

rulers whom later generations did not regard as 'legitimate' or acceptable to the gods. No lists have yet been discovered

which are of a later date than the reign of Ramesses II, and even the extant tables are damaged or incomplete.

Further problems are encountered in attempting to establish an accurate chronology, because the ancient Egyptians did

not date their inscriptions using the same kind of consecutive system that we follow today, such as 1900 BC or 1300 AD.

Instead, from the 11th Dynasty onwards, events were dated in terms of the regnal years of each ruler, for example, 'In Year

Five of King Amenhotep III'. Since we do not have complete details about the consecutive order of the reigns, nor the full

length of each reign, there is difficulty in trying to determine the real date (in our terms of reckoning) of a monument

or an event.

Even the evidence provided by Manetho's history, the various king lists, and the many other extant inscriptions, which

give the names and dates of kings, is insufficient to establish an accurate chronology of ancient Egypt. This is because

none of these sources provides a complete sequence of kings or gives full details of the lengths of their reigns. Also,

historical inscriptions have not survived from every period, and for some reigns the surviving evidence is very scanty.

It is not even possible to compile an accurate consecutive list of rulers, as there were co-regencies (when a king and his

designate successor ruled together for a time) and there were times when kings or even dynasties ruled in different areas

of the country simultaneously, but each dated their key events and monuments to the regnal years of the different rulers.

To establish a basis for an absolute chronology, it has been necessary for Egyptologists to seek other evidence. For

the later periods in particular, historians have been able to use comparative archaeological and inscriptional evidence

from other Near Eastern civilisations, from the Bible, and from the writings of the Greek author Herodotus. It has also

been possible to rely on astronomy to fix particular dates, particularly those associated with the heliacal rising of the

dog-star Sirius (the Greek Sothis).

Within that framework it is generally accepted that while there are many errors in Manetho’s preserved chronology and

often major inconsistencies with other more reliable evidence, the original Manetho chronology does appear to have been

based on authentic and reliable source materials. As discoveries emerge there is still a tendency to compare the conclusions

with what appears in Manetho.

The Josephus account, which appears in his book Against Apion, covers

only a portion of Manetho’s history, spanning approximately from the 15th to the 19th Dynasties. His account appears in

narrative form and contains no reference to numbered dynasties or any direct reference to dynastic divisions, although it

does describe shifts in control from one political faction to another that is somewhat consistent with the corresponding

dynastic divisions. It also includes some sequences of named Egyptian rulers along with lengths of reign and some collective

durations for groups of kings. His recitation of the named kings and their lengths of reign frequently disagree with what

we know from the archaeological record. We will discuss these variations and their causes in more detail in subsequent chapters.

He appears to have had at least two versions of Manetho’s history to work from and these earlier copies of Manetho already

exhibit evidence of inconsistencies in transmission. For example, referring to Manetho’s account of a group of kings known

as the Hyksos, Josephus says that in one account the definition of Hyksos means "king-shepherds" but that in another version

it means "captive shepherds." In another instance, in one place he gives one set of personal names to the Egyptian kings

who defeated the Hyksos and elsewhere he gives another set of personal names to these same kings.

Later accounts, by Africanus and Eusebius, are similar to each other in that they both take the form of tabular accounts

of the various dynasties in sequential order along with, in most cases, a list of kings within each dynasty and their lengths

of reign. And, in most instances, they parallel each other closely as to the sequence of dynasties and kings contained within.

Neither contains much narrative material about the kings although a few very short anecdotes are preserved.

Both seem to draw on similar source materials (Eusebius may have partially drawn on Africanus) and follow the same sequential

structure, there are several points where the two lists diverge with respect to the chronological information about particular

kings and dynasties. Scholars generally consider Africanus more accurate than Eusebius with regard to the transmission of

the Manetho texts, and it is clear that on occasion Eusebius has a more garbled source than does Africanus.

Note - both the Africanus and Eusebius lists are preserved only in copies written down in later times by other writers,

allowing additional opportunities for error in the copying and interpreting process. The Africanus material comes chiefly

from a work by George the Monk (aka Syncellus) who wrote it down at about the end of the 8th century AD.

Syncellus (George the Monk) also preserves some material that he attributes to Manetho as independent of and different from

Africanus and Eusebius. Known as The Book of Sothis, it appears to be somewhat of an ancient forgery, a pseudo-Manetho that

does suggest some familiarity with Manetho. Syncellus also preserves another document called The Old Chronicle, which he

believes to have influenced Manetho and led him into error. That document, however, is probably post-Manetho but may have

in fact been a fourth independent preservation of Manetho’s account. It was concerned primarily with the reigns of the gods

and we need not concern ourselves with it at this point.

Josephus's account runs the 18th and 19th Dynasties together without any indication of a break between them, and places

scattered pieces of chronological information about the 19th Dynasty in different parts of the text, again without indicating

any dynastic break between the 18th and 19th Dynasties.

Africanus and Eusebius partially follow Josephus but they also have a separate listing for the 19th Dynasty. Obviously,

at least one editor between Josephus and Africanus made some new judgments about how to extract and organize data from Manetho’s

text.

Judging from the references in Josephus that show him using more than one copy of Manetho, we also see that inconsistencies

and contradictions had already crept into the transmissions before Josephus prepared his own work. In some instances there

were slightly different versions of stories that appeared in the two texts, suggesting that the copiers may have been paraphrasing

Manetho rather than precisely copying from his manuscript, and either Josephus or his source appears to have concatenated

these alternative accounts as if they were separate sequential events. Josephus’s two copies of Manetho even appear to have

different names for some of the people who performed the acts in questions.

So, what the various versions show us is that errors were already entering into the transmission of Manetho’s text not long

after he wrote his original manuscript, and eventually, those interested in what he had to say were concerned almost exclusively

with his chronological accounts. Assorted redactors attempted to extract chronological material from the already confusing

and contradictory set of manuscripts and compiled lists of rulers in chronological order. This produced a variety of independent

error-ridden sources that found there way into Josephus, Africanus and Eusebius, and it is from the pattern of errors that

we will attempt to reconstruct Manetho’s original chronology.

| Sources | Manetho's Chronology Restored, draft of the first chapter of Manetho's Chronology

Restored. The Experience of Ancient Egypt, Rosalie David |