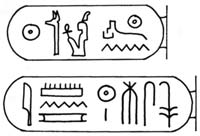

Pre-nomen is usermaatre setepenre, translation: The Justice of Re is Powerful, Chosen of

Re, transliteration: wsr-mAat-ra stp.n-ra After its arrival in The British Museum the 'Younger

Memnon' was perhaps the first piece of Egyptian sculpture to be recognized as a work of art by connoisseurs, who traditionally

judged things by the standards of ancient Greek art.

The Trustees of the British Museum purchased the sculpture from Henry Salt in 1822. For several years it was displayed in

the old Townley Galleries (now demolished). By 1834 the present Egyptian Sculpture Gallery had been built. Because of the

enormous weight of some of these sculptures, the Museum had to call on the help of the Army to move them into the new gallery. Related articles  Ramesses II, "the

Great", ruled 1279-1213 BC

Ramesses II, "the

Great", ruled 1279-1213 BC

Ramesses II became the third

king of the 19th Dynasty at the age of twenty-five. In his sixty-seven year reign he probably built more temples and sired

more children than any other Egyptian king. Today, he is often called Ramesses 'the great'.

He founded a new capital, Pi-Ramesse in the eastern Delta, which remained the royal residence throughout the Ramesside period.

He also built a vast number of temples throughout Egypt and Nubia. The most famous of these are the rock cut temple at Abu

Simbel, and his mortuary temple at Thebes, the Ramesseum. The tomb of his principal wife, Nefertari, at Thebes is one of

the best-preserved royal tombs. The tomb of many of his sons has also recently been found in the Valley of the Kings (KV5).

Ramesses II was buried in the Valley of the Kings and his body was found in the Deir el-Bahari cache.

He founded a new capital, Pi-Ramesse in the eastern Delta, which remained the royal residence throughout the Ramesside period.

He also built a vast number of temples throughout Egypt and Nubia. The most famous of these are the rock cut temple at Abu

Simbel, and his mortuary temple at Thebes, the Ramesseum. The tomb of his principal wife, Nefertari, at Thebes is one of

the best-preserved royal tombs. The tomb of many of his sons has also recently been found in the Valley of the Kings (KV5).

Ramesses II was buried in the Valley of the Kings and his body was found in the Deir el-Bahari cache.

For Ramesses II, the most momentous event in his reign was the battle of Kadesh, fought against the Hittites. On his monuments,

the battle was commemorated as a great victory. However, the Hittite account, found at their capital, Hattusas, suggests

that the battle was closer fought.

Nomen is ramesisu meriamon, translation: Born of Re, beloved of Re, transliteration: ra-msi-sw mri-imn

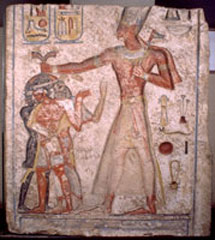

Bust of a granite statue of

Ramesses II

From Aswan, Elephantine Island, 19th Dynasty, around 1250 BC

From the Temple of Khnum

Many of the main attributes of Egyptian royalty are visible on this statue of King

Ramesses II (1279-1213 BC). He is shown

wearing the two crowns of Upper and Lower Egypt, symbolizing the king's control over the country; in his hands are the crook

and the flail, which represent his power over his subject; and on his brow is the Uraeus, the cobra snake ready to attack

any who dare to oppose him.

The beard he wears would have been false (though perhaps made of real hair) and is shown attached to his crown using straps

which probably fastened round the ear. The beard is of a type only worn by the king; the beards of gods tend to curl at

the ends, while those of ordinary people are shown as much shorter. The king's names are cut on his shoulders, he wears

a collar, and there is an elaborate bracelet on his right wrist.

Colossal bust of Ramesses II, the 'Younger Memnon'

From the Ramesseum, Thebes, 19th Dynasty, about 1250 BC

One of the largest pieces of Egyptian sculpture in the British Museum

Ramesses II succeeded his father Sety I in around 1279 BC and ruled for 67 years.

Weighing 7.25 tons, this fragment of his statue was cut from a single block of two-coloured granite. He is shown wearing

the Nemes head-dress surmounted by a cobra diadem. The sculptor has used a slight variation of normal conventions to relate

his work to the viewer, angling the eyes down slightly, so that the statue relates more to those looking at it. It was retrieved

from the mortuary temple of Ramesses at Thebes (the 'Ramesseum') by Giovanni Belzoni in 1816. Belzoni wrote a fascinating

account of his struggle to remove it, both literally, given its colossal size, and politically. The hole on the right of

the torso is said to have been made by members of Napoleon's expedition to Egypt at the end of the eighteenth century, in

an unsuccessful attempt to remove the statue. The imminent arrival of the head in England in 1818 inspired the poet Percy

Bysshe Shelley to write Ozymandias.

William Alexander, Installing the Bust of

Ramesses II in the

Egyptian Sculpture Gallery

The British Museum, London, England, May 1834

The colossal stone bust of the Egyptian king Ramesses II weighs 16 tons and dates from about 1270 BC. It was sent to England

in 1816 by Henry Salt, the British Consul-General in Egypt. At the start of its journey it was tied to wooden rollers, on

which it was pulled by ropes to the banks of the River Nile by hundreds of workmen. It was then floated down the river and

taken to England by ship.

Alexander made this sketch while he was watching the head being lifted into place. It shows soldiers of the Royal Engineers

using heavy ropes and lifting equipment under the command of Major Charles Cornwallis Dansey (the figure sitting towards

the front of the scene). Dansey had fought at the Battle of Waterloo nearly twenty years earlier, and had received a wound

which had left him lame. For this reason he was allowed to sit while directing his men.

Ozymandias,

Percy Bysshe Shelly (1792 - 1822)

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert… Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

"My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings,

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!"

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away."

Shelly's couplet is similar to Diodorus's writing (the only classical author to mention Ozymandias) - Shelly, Banks etc

were classical student. Diodorus wrote "I am Ozymandias, king of Kings. If anyone would know how great I am

and where I lie let him surpass any of my works". He also wrote that the statue of Ozymandias was "... the biggest

of all those amongst the Egyptians". It is accepted that the name Ozymandias is derived from Usermare (Ramesses II

pre-nomen meaning Justice of Re is Powerful, Chosen of Re).

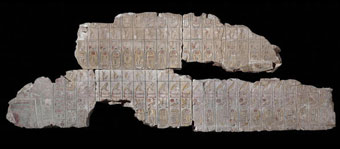

Fragment of the Kings List of Ramesses

and Sety I's temples at Abydos - British Museum

Glazed stealite plaque, Ashmolean Museum

Fragment of panel commemorating the Coronation - Bristol Museum

Figure of a falcon inscribed , 19th Dynasty from Tell el-Maskhuta

- British Museum

Wooden coffin lid - Cairo Museum

One

of a pair of armlets in gold with inlays - Cairo Museum

Dark granite statue of a 12th

or 13th Dynasty king, usurped by Ramesses II - Cairo Museum

Relief showing

Ramesses about to

smite prisoners - Cairo Museum

Head of Ramesses carved from Red Granite, reused in the Temple

of Bast, Bubastis - Liverpool Museum

Base for a Statue, traditional enemies of Egypt and vassals

carved on the block - Liverpool Museum

Statue of Mut, carved in Calcite - Luxor Museum

Alabaster 'Pilgrim bottle' with Gold mountings

and blue cartouches of Ramesses and Queen Nefertari - Petrie Museum

Prince Khaemwaset offering

to the god Ptah in the form of the Apis Bull, son of Ramesses - Rosicrucian Museum

Statue of Ramesses

II (the Great) - Museo Egizio di Turino

Stela of Ramose and Mutemula

- Museo Egizio di Turino

Turin Royal Canon - Museo Egizio di Turinoa

Relief showing Setau, a viceroy of Ramesses

II making an offering to Renenutet - British Museum

Sandstone relief showing Setau, a viceroy of Ramesses II making an offering to Renenutet - British Museum

Black granite statue from Nebesheh (in the Nile

Delta) - Boston Museum Limestone statue - Fitzwilliam

Museum

Earthenware Funerary Cone - Fitzwilliam Museum

Quartzite statue of Nefer-Tari, wife of

Ramesses

II - Fitzwilliam Museum

Clay plaque mould for a Cartouche - Fitzwilliam

Museum