Amenhotep IV

is better known as Akhenaten, the new name he took early on in

his reign-ushered in a revolutionary period in Egyptian history. The Amarna

Interlude, as it is often called, saw the removal of the seat of government

to a short-lived new capital city, Akhetaten which means horizon of the Aten (modern el-Amarna), the

introduction of a new art style, and the elevation of the cult of the sun

disc, the Aten, to pre-eminent status in Egyptian religion. This last heresy

in particular was to bring down on Akhenaten, and his immediate successors,

the scorn of later kings.

Amenhotep IV

is better known as Akhenaten, the new name he took early on in

his reign-ushered in a revolutionary period in Egyptian history. The Amarna

Interlude, as it is often called, saw the removal of the seat of government

to a short-lived new capital city, Akhetaten which means horizon of the Aten (modern el-Amarna), the

introduction of a new art style, and the elevation of the cult of the sun

disc, the Aten, to pre-eminent status in Egyptian religion. This last heresy

in particular was to bring down on Akhenaten, and his immediate successors,

the scorn of later kings.  The

young prince was at least the second son of Amenhotep III by his chief wife,

Tiy: an elder brother, prince Tuthmosis, had died prematurely (strangely, a

whip bearing his name was found in Tutankhamun's tomb KV62). There is some

controversy over whether or not Amenhotep III took his son into partnership

on the throne in a co-regency and there are quite strong arguments both for and

against. A point in favour of a co-regency is the appearance during the

latter years of Amenhotep III's reign of artistic styles that are

subsequently seen as part of the 'revolutionary' Amarna art introduced by

Akhenaten; on the other hand, both 'traditional' and 'revolutionary' art

styles could easily have co-existed during the early years of Akhenaten's

reign. At any rate, if there had been a co-regency, it would not have been

for longer than the short period before the new king assumed his preferred

name of Akhenaten in regnal Year 5.

The

young prince was at least the second son of Amenhotep III by his chief wife,

Tiy: an elder brother, prince Tuthmosis, had died prematurely (strangely, a

whip bearing his name was found in Tutankhamun's tomb KV62). There is some

controversy over whether or not Amenhotep III took his son into partnership

on the throne in a co-regency and there are quite strong arguments both for and

against. A point in favour of a co-regency is the appearance during the

latter years of Amenhotep III's reign of artistic styles that are

subsequently seen as part of the 'revolutionary' Amarna art introduced by

Akhenaten; on the other hand, both 'traditional' and 'revolutionary' art

styles could easily have co-existed during the early years of Akhenaten's

reign. At any rate, if there had been a co-regency, it would not have been

for longer than the short period before the new king assumed his preferred

name of Akhenaten in regnal Year 5. The beginning of Akhenaten's reign marked no great discontinuity with that of his predecessors. He was crowned at Karnak (temple of the god Amun) and, like his father, married a lady of non-royal blood, Nefertiti, the daughter of the vizier Ay. Ay seems to have been a brother of Queen Tiy and the son of Yuya and Tuya. Nefertiti's mother is not known; she may have died in childbirth or shortly afterwards, since Nefertiti seems to have been brought up by another wife of Ay named Tey, who would then be her stepmother.

Akhenaten, the

tenth king of

the 18th Dynasty, was perhaps the most controversial because of his

break with traditional religion. Some say that he was the most remarkable

king to sit upon Egypt’s throne. There can be little doubt that the new king

was far more of a thinker and philosopher than his forebears. Akhenaten was

traditionally raised by his parents, Amenhotep III and Queen Tiy (1382-1344

BC) by worshipping Amun. Akhenaten, however, preferred Aten, the sun god

that was worshipped in earlier times. Amenhotep III had recognized the

growing power of the priesthood of Amun and had sought to curb it; his son

was to take the matter a significantly further by introducing a new monotheistic cult

of sun-worship that was incarnate in the sun's disc, the Aten. When early in

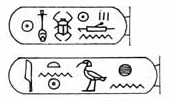

his reign he changed his name to Akhenaten, meaning “He Who is of Service to

Aten”, he also renamed his queen to Nefer-Nefru-Aten, which is “Beautiful is

the Beauty of Aten.”

Akhenaten, the

tenth king of

the 18th Dynasty, was perhaps the most controversial because of his

break with traditional religion. Some say that he was the most remarkable

king to sit upon Egypt’s throne. There can be little doubt that the new king

was far more of a thinker and philosopher than his forebears. Akhenaten was

traditionally raised by his parents, Amenhotep III and Queen Tiy (1382-1344

BC) by worshipping Amun. Akhenaten, however, preferred Aten, the sun god

that was worshipped in earlier times. Amenhotep III had recognized the

growing power of the priesthood of Amun and had sought to curb it; his son

was to take the matter a significantly further by introducing a new monotheistic cult

of sun-worship that was incarnate in the sun's disc, the Aten. When early in

his reign he changed his name to Akhenaten, meaning “He Who is of Service to

Aten”, he also renamed his queen to Nefer-Nefru-Aten, which is “Beautiful is

the Beauty of Aten.” This was not in itself a new idea: as a relatively minor aspect of the sun god Re-Harakhte, the Aten had been venerated in the Old Kingdom and a large scarab of Akhenaten's grandfather Tuthmosis IV (now in the British Museum) has a text that mentions the Aten. Rather, Akhenaten's innovation was to worship the Aten in its own right. Portrayed as a solar disc whose protective rays terminated in hands holding the ankh hieroglyph for life, the Aten was accessible only to Akhenaten, thereby removing the need for an intermediate priesthood. In one way this was exceptionally cunning (by excluding the cult from it's power base) alternatively the resistance from the cult was significant. The people were to worship Akhenaten, as the Aten's manifestation on earth.

At first, the king built a temple to his god Aten immediately outside the east gate of the temple of Amun at Karnak, but clearly the co-existence of the two cults could not last. He therefore proscribed the cult of Amun, closed the god's temples, took over the revenues. He then sent his officials around to destroy Amen’s statues and to desecrate the worship sites. These actions were so contrary to the traditional that opposition arose against him. The estates of the great temples of Thebes, Memphis and Heliopolis reverted to the throne. Corruption grew out of the mismanagement of such large levies. To make a complete break, in Year 6 the king and his family, left Thebes and moved to a new capital in Middle Egypt, half way between Memphis and Thebes. It was a virgin site, not previously dedicated to any other god or goddess, and he named it Akhetaten - The Horizon of the Aten. Today the site is known as el-Amarna.

A limestone slab, with traces of the draughtsman's grid still on it, found in the Royal Tomb of Amarna. Its style is characteristic of the early period of Akhenaten's reign. The king is accompanied by Nefertiti and just two of their daughters, but this does not necessarily indicate that these are the eldest, since others of the six may have been omitted.

In the tomb of Ay, the chief minister of Akhenaten (and later to become king after Tutankhamun's death), occurs the longest and best rendition of a composition known as the 'Hymn to the Aten', said to have been written by Akhenaten himself. This has some similarities to Psalm 104 and to the Canticle of the Sun by Francis of Assisi. The Hymn sums up the whole ethos of the Aten cult and especially the concept that only Akhenaten had access to the god: 'Thou arisest fair in the horizon of Heaven, 0 Living Aten, Beginner of Life…there is none who knows thee save thy son Akhenaten. Thou hast made him wise in thy plans and thy power.' No longer did the dead call upon Osiris to guide them through the after-world, for only through their adherence to the king and his intercession on their behalf could they hope to live eternally beyond the grave.

According to present evidence, however, it appears that it was only the upper echelons of society which embraced the new religion with any fervour (and perhaps that was only skin deep). Excavations at Amarna have indicated that even here the old way of religion continued among the ordinary people. On a wider scale, throughout Egypt, the new cult does not seem to have had much effect at a common level except, of course, in dismantling the priesthood and closing the temples; but then the ordinary populace had had little to do with the religious establishment anyway, except on the high days and holidays when the god's statue would be carried in procession from the sanctuary outside the great temple walls.

The standard bureaucracy continued its efforts to run the country while the king courted his god. Cracks in the Egyptian empire may have begun to appear in the later years of the reign of Amenhotep III; at any rate they became more evident as Akhenaten increasingly left government and diplomats to their own devices. Civil and military authority came under two strong characters: Ay, who held the title 'Father of the God' (and was probably Akhenaten's father-in-law), and the general Horemheb (also Ay's son-in-law since he married Ay's daughter Mutnodjme, sister of Nefertiti). Both men were to become pharaoh before the 18th Dynasty ended. This redoubtable pair of closely related high officials no doubt kept everything under control in a discreet manner while Akhenaten pursued his own philosophical and religious interests.

A new artistic style

A new artistic style The power behind the throne?

The sandstone building slab (talatat) shows Akhenaten wearing the Red Crown and offering to the Aten's disk, whose descending rays extend the Ankh sign of life to him. Tragedy seems to have struck the royal family in about Year 12 with the death in childbirth of Nefertiti's second daughter, Mekytaten; it is probably she who is shown in a relief in the royal tomb with her grief-stricken parents beside her supine body, and a nurse standing nearby holding a baby. The father of the infant was possibly Akhenaten, since he is also known to have married two other daughters, Meretaten (not to be confused with Mekytaten) and Akhesenpaaten (later to become Tutankhamun's wife).

Nefertiti appears to have died soon after Year 12, although some suggest that she was disgraced because her name was replaced in several instances by that of her daughter Meretaten, who succeeded her as 'Great Royal Wife'. The latter bore a daughter called Meretaten-tasherit (Meretaten the Younger), also possibly fathered by Akhenaten. Meretaten was to become the wife of Smenkhkare, Akhenaten's brief successor. Nefertiti was buried in the royal tomb at Amarna, judging by the evidence of a fragment of an alabaster ushabti figure bearing her cartouche found there in the early 1930s.

Akhenaten died c.1334 BC, probably in his 16th or 17th year. Evidence found by Professor Geoffrey Martin during re-excavation of the royal tomb at Amarna showed that blocking had been put in place in the burial chamber, suggesting that Akhenaten was buried there initially. Others do not believe that the tomb was used, however, in view of the heavily smashed fragments of his sarcophagus and canopic jars recovered from it, and also the shattered examples of his ushabtis - found not only in the area of the tomb but also by Petrie in the city.

Amongst the distinctly 18th Dynasty jewellery found cached outside the Royal Tomb at Amarna the small gold ring with Nefertiti cartouche is particularly significant. What is almost certain is that his body did not remain at Amarna. A burnt mummy seen outside the royal tomb in the 1880s, and associated with jewellery from the tomb (including a small gold finger ring with Nefertiti's cartouche, was probably Coptic, as was other jewellery nearby. Akhenaten's adherents would not have left his body to be despoiled by his enemies once his death and the return to orthodoxy unleashed a backlash of destruction. It has been suggested that he was buried in tomb KV55, though other possibilities are also likely.

Arguably, to those who are not very involved in the study of ancient Egypt, Queen Nefertiti is perhaps better known then her husband, the heretic king Akhenaten (Amenhotep IV). It is said that even in the ancient world, her beauty was famous, and her famous statue, found in a sculptor's workshop, is not only one of the most recognizable icons of ancient Egypt, but also the topic of some modern controversy. She was more than a pretty face however, for she seems to have taken a hitherto unprecedented level of importance in the Amarna period of Egypt's 18th Dynasty. In artwork, her status is evident and indicates that she had almost as much influence as her husband. For example, she is depicted nearly twice as often in reliefs as her husband, at least during the first five years of his reign. Indeed, she is once even shown in the conventional pose of a pharaoh smiting his (or in this case, her) enemy.

Family Line

Nefertiti may or may not have been of royal blood. She was probably a daughter of the army officer, and later pharaoh, Ay, who may in turn have been a brother of Queen Tiye. Ay sometimes referred to himself as "the God's father", suggesting that he may have been Akhenaten's father-in-law, though there is no specific references for this claim. However, Nefertiti's sister, Mutnojme, is featured prominently in the decorations of Ay's tomb in the Valley of the Kings on the West Bank at Thebes (modern Luxor). However, while we know that Mutnojme was certainly the sister of Nefertiti, her prominence in Ay's tomb clearly does not guarantee her relationship to him. Others have suggested that Nefertiti may have been a daughter of Tiye, or that she was Akhenaten's cousin. Nevertheless, as "heiress", she may have also been a descendant of Ahmose-Nefertari, though she was never described as God's wife of Amun. However, she never lays claim to King's Daughter, so we certainly know that she cannot have been an heiress in the direct line of descent. If she was indeed the daughter of Ay, it was probably not by his chief wife, Tey, who was not referred to as a "Royal mother of the chief wife of the king", but rather 'nurse' and 'governess' of the king's chief wife. It could be that Nefertiti's actual mother died early on, and it was left to Tey to raise the young girl. However, many other explanations have also been suggested.

Personal Life and the Relationship of King and Queen

Together, we know that Akhenaten and Nefertiti has six daughters, though it was probably with another royal wife called Kiya that the king sired his successors, Smenkhkare and Tutankhamun. Nefertiti also shared her husband with two other royal wives named Metetaten and Akhesenpaaten, as well as later with her probable daughter, Merytaten. Undoubtedly, Akhenaten seems to have had a great love for his Chief Royal wife. They were inseparable in early reliefs, many of which showed their family in loving, almost utopian compositions. At times, the king is shown riding with her in a chariot, kissing her in public and with her sitting on his knee. One eulogy proclaims her:

"And the Heiress, Great in the Palace, Fair of Face, Adorned with the Double Plumes, Mistress of Happiness, Endowed with Favours, at hearing whose voice the King rejoices, the Chief Wife of the King, his beloved, the Lady of the Two Lands, Neferneferuaten-Nefertiti, May she live for Ever and Always"

However, it was the figure of Nefertiti that Akhenaten had carved onto the four corners of his granite sarcophagus and it was she who provided the protection to his mummy, a role traditionally played by the female deities Isis, Nephthys, Selket and Neith. One influence within the personal lives of Nefertiti and Akhenaten must have been the presence of Akhenaten's mother, Tiye. Tiye would have held a special position as a wise woman in his court, and we can only surmise that this must have had some affect on the younger couple's relationship.

Queen Tiye as the "wise woman" of El Amarna was often depicted with facial features that not only signalled old age, but life experience and wisdom calling for respect and even veneration. When Nefertiti's face is represented with the first signs of old age, this may well signify that she has assumed the position of "wise woman" following the death of Tiye, at which point her court status would have been even further elevated.

The Religion

Nefertiti and her King lived during a highly unusual period in Egyptian history. It was a time of religious controversy when the traditional gods of Egypt were more or less abandoned at least by the royal family in favour of a single god, the sun disk named Aten. However, it should be noted that the Egyptian religion did not actually become monotheistic, for cults related to the other gods did persist and they were never really erased from the Egyptian theology.

It is believed that Nefertiti was active in the religious and cultural changes initiated by her husband (some even maintain that it was she who initiated the new religion). She also had the position as a priest, and she was a devoted worshipper of the god Aten. In the royal religion, the King and Queen were viewed as "a primeval first pair". It was they who worshipped the sun disk named Aten and it was only through them that this god was accessed. Indeed, the remainder of the population was expected to worship the royal family, as the rays of the sun fell and gave life to, it would seem, only the royal pair.

However, many scholars presume that the Mutnodjme who later married King Horemheb is none other than the younger sister of Nefertiti. In Akhenaten: King of Egypt by Cyril Aldred, the author explains that a fragmentary statue of Mutnodjme discovered at Dendera describes her not only as "Chief Queen", but also "God's Wife [of Amun]", which he explains puts her in the line of those other great consorts who traced their descent from Ahmose-Nefertari. This links both sisters to the cult of Amun, which he tells us could obviously not have been openly proclaimed at Amarna.

Yet we must be very careful with this link between Nefertiti and Amun by way of her sister's later attachment to the cult. Horemheb considered himself to be an adamant restorer of the old religion after the Amarna period, and so just because his Chief Queen took the title of God's Wife does not necessarily mean that Nefertiti held any real interest in that cult.

Doubtless though, Nefertiti may very well, and probably did participate in a similar manner as God's Wife in the cult of Re-Atum. Unlike other chief queens, she is shown taking part in the daily worship, repeating the same gestures and making similar offerings as the king. Where traditionally a relationship existed between God and King, now that relationship is expanded to include the royal pair.

She in fact exhibits the same fashion as God's Wife. From her first appearance at Karnak, she wears the same clinging robe tied with a red sash with the ends hanging in front. She also wears the short rounded hairstyle. In her case, this was exemplified by a Nubian wig, the coiffure of her earlier years, alternating with a queens tripartite wig, both secured by a diadem bearing a double uraei. Sometimes this was replaced by a crown with double plumes and a disk, like Tiye and her later Kushite counterparts.

She dressed for appeal, and if she fulfilled a similar function as God's wife of Amun in the Amarna religion, part of this responsibility would have been to maintain a state of perpetual arousal. However, since the Aten was intangible and abstract, this appeal must be to his son the king. Ay praises her for "joining with her beauty in propitiating the Aten with her sweet voice and her fair hands holding the sistrums".

In fact, as the wife of the sun god's offspring, she took on the role of Tefnut, who was the daughter and wife of Atum. After the fourth regal year, she began to wear a mortar-shaped cap that was the headgear of Tefnut in her leonine aspect of a sphinx. She was then referred to as "Tefnut herself", at once the daughter and the wife of the sun-god. Therefore, Nefertiti played an equal role with the king who was the image of Re. Of course, as a god, no mortal could claim to be her mother, which may be the reason why Tey must content herself with the titles of "Wet-nurse" and "Governess" In fact, it may have been that she hid her parentage to conceal the fact that the progenitors of this high and mighty princess were not also equally divine.

Nefertiti's Disappearance

Towards the end of Akhenaten's reign, Nefertiti disappeared from historical Egyptian records. For a number of years, scholars though that she had fallen from grace with the king, but this was actually a case of mistaken identity. It was Kiya's name and images that were removed from monuments, and replaced by those of Meryetaten, one of Akhenaten's daughters. It has been suggested, though there is no hard supporting evidence, that by year twelve of Akhenaten's reign, and after bearing him a son and possibly a further daughter, Kiya became too much of a rival to Nefertiti and that it was she who caused Kiya's disgrace. It is possible that Nefertiti disappearance a number of years after that of Kiya's simply meant that she died around the age of thirty, though there are controversies on this matter as well. It may not be simple coincidence that, shortly after Nefertiti's disappearance from the archaeological record, Akhenaten took on a co-regent with whom he shared the throne of Egypt. This co-regent has been a matter of considerable speculation and controversy, with a whole range of theories. One such theory puts forward the idea that the co-regent was none other than Nefertiti herself in a new guise as a female king following the lead of women such as Sobkneferu and Hatshepsut. Another theory is that there were actually two co-regents, consisting of a male son named Smenkhkare, and Nefertiti under the name Neferneferuaten, both of whom adopted the prenomen, Ankhkheperure. Undoubtedly, like her husband who was originally named Amenhotep, she too took the new name, Neferneferuaten to honour the Aten (Neferneferuaten can be translated as "The Aten is radiant of radiance [because] the beautiful one is come" or "Perfect One of the Aten's Perfection"). Indeed, she may have even changed her name prior to her husband doing so, but rather this means she also served as co-regent is questionable.

Some scholars are considerably adamant about Nefertiti assuming the role of co-regent, and even serving as king for a short time after the death of Akhenaten. One such individual is Jacobus Van Dijk, responsible for the Amarna section of the Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. He believes that Nefertiti indeed became co-regent with her husband, and that her role as queen consort was taken over by her eldest daughter, Meryetaten (Meritaten). If this is true, then Nefertiti may have even taken up residence in Thebes, as evidenced by a graffito dated to year three in the reign of Neferneferuaten mentioning a "Mansion of Ankhkheperure". If so, there could have been an attempt made at reconciliation with the old cults. He also suggests that Smenkhkare might have also been Nefertiti, ruling after the death of her husband, with her own daughter acting in a ceremonial role of "Great Royal Wife".

However, other scholars are equally adamant against Nefertiti ever having been a co-regent or ruling after her husband's death. In his book, Akhenaten: King of Egypt, Cyril Aldred references a funerary objected called a shabti. On it was inscribed:

"The Heiress, high and mighty in the palace, one trusted [of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt (Neferkheperure, Wa'enre), the son of Re (Akhenaten), Great in] his Lifetime, the Chief Wife of the King (Neferneferuaten-Nefertiti), Living for Ever and Ever."

More Recent Controversy

Nefertiti is perhaps best remembered for the painted limestone bust depicting her. Many consider it one of the greatest works of art of the pre-modern world. Sometimes known as the Berlin bust, it was found in the workshop of the famed sculptor Thutmose. This bust depicts her with full lips enhanced by a bold red.

Although the crystal inlay is missing from her left eye, both eyelids and brows are outlined in black. Her graceful elongated neck balances the tall, flat-top crown which adorns her sleek head. The vibrant colours of the her necklace and crown contrast the yellow-brown of her smooth skin. While everything is sculpted to perfection, the one flaw of the piece is a broken left ear. Because this remarkable sculpture is still in existence, it is no wonder why Nefertiti remains 'The Most Beautiful Woman in the World.'

The artwork is the brainchild of a Hungarian duo called Little Warsaw, and involved lowering the head of Nefertiti on to the headless bronze statue of a woman wearing a tight-fitting transparent robe. This angered a number of officials in Egypt for several reasons. First of all, it must be remembered that Egypt is a rather conservative society and the attachment of Nefertiti's head to an almost nude statue was seen as an affront to Egyptian sensibilities. However, it was also pointed out by some Egyptian Egyptologists that such a display might give rise to some damage to the bust.

Irregardless, this controversy is probably short lived. The display apparently only lasted for a few hours and so the controversy has largely been mitigated at this point.

A recent, more enduring controversy surrounding Nefertiti is the possible discovery of her mummy, or at least the new identification of a previously known mummy. Soon after the incident involving Nefertiti's bust, Joanne Fletcher announced that she had identified the actual mummy of the queen. In 1898, the French Egyptologist Victor Loret excavated the tomb of Amenhotep II on the Theban necropolis and came upon a remarkable find. This was the first tomb ever opened in which the Pharaoh was still in his original resting place, and, moreover, eleven other mummies were also discovered in a sealed chamber in the tomb. All but three of these mummies, due to their critical state of preservation, were transferred to the Egyptian Antiquities Museum in Cairo.

One of the three mummies that were left behind became known among Egyptologists as the "Younger Lady" and since then Egyptologists have swayed between believing this corpse to be either Nefertiti or Princess Sitamun, a daughter of Amenhotep III. Fletcher investigated the tomb 2002 after identifying a Nubian style wig worn by royal women during Akhenaten's reign. She also pointed to other clues that suggest that this mummy might indeed be Nefertiti, such as a doubled-pierced ear lobe, which she claims was a rare fashion statement in Ancient Egypt.

There is a puzzle, she conceded, and explained that in 1907, when Egyptologist Grafton Elliot Smith first examined the three mummies, he reported that the Younger Lady was lacking a right arm. Nearby, however, he had found a detached right forearm, bent at the elbow and with clenched fingers. She said that the mummy had deteriorated badly; that the skull was pierced with a large hole, and the chest hacked away. Worse still, the face, which would otherwise have been excellently preserved, had been cruelly mutilated, the mouth and cheek no more than a gaping hole. Further examination using a Canon digital X-ray machinery, the team spotted jewellery within the smashed chest cavity of the mummy. They also noticed a woman's severed arm beneath the remaining wrappings. The arm was bent at the elbow in Pharaonic style with its fingers still clutching a long-vanished royal sceptre.

Following Discovery Channel's coverage of the events, the identification of the Younger Lady's mummy as Nefertiti immediately attracted an eager audience and made headlines around the world. Because the story's release was via a very unusual route, and review by fellow egyptologists did not happen, there was a reaction to the sensationalism produced by Joanne who had recently received her doctorate. But Egyptologists are not so convinced. In fact, they are divided into two schools of thought.

Others express doubt that the remains are those of the legendary queen of beauty. Egyptologist Susan James, who trained at Cambridge University and who spent a long time studying the three mummies, told Discovery Channel, who financed the expedition, " What we know about mummy 61072 would indicate that it is one of the young females of the late 18th dynasty, very probably a member of the royal family. However, physical evidence known and published prior to this expedition indicates the unlikelihood of this being the mummy of Nefertiti. Without any comparative DNA studies, statements of certainty are wishful thinking."

Secretary-General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA) Zahi Hawass totally refutes the idea, and describes it as "pure fiction". He accuses Fletcher of lacking in experience, as "a new PhD recipient", and that Fletcher's theory was not based on facts or solid evidence, "only on facial resemblance between the mummy and Nefertiti's bust, and on artistic representations of the Amarna period in which the queen lived". Dr. Hawass asserted, moreover, that the physical resemblance is not significant, "because all the statues of the Amarna era have the same characteristics. Amarna art was idealistic and not realistic," he said, and pointed out that in the Egyptian Museum, there were five of six mummies with the same characteristics. Mamdouh El-Damati, director of the Egyptian Museum, mentioned that this theory was not new, this being the second time that a claim to have discovered Nefertiti's mummy within this group of mummies had been made.

- Related articles

- Amarna Princess - Bolton Museum

- Coffin found in KV55 - Cairo Museum

- Akhenaten and el-Amarna The King's Lost City

- Relief depicting of Nefertiti - Ashmolean Museum

- Limestone trial piece of Nefertiti - Petrie Museum

- Storage jar decorated with a hippopotamus from el-Amarna - Ashmolean Museum

- Blue painted pottery jar lid from el-Amarna - Bolton

- Images of Akhenaten in the Cairo Museum

- Head of a statue of Amenhotep IV, Akhenaten - Luxor Museum

- Reconstructed wall from Amarna - Luxor Museum

- Relief of Akhenaten - Luxor Museum

- Daughter's of Akhenaten and Nefertiti - Metropolitan Museum

- Relief showing Akhenaten making an offering to Aten - Metropolitan Museum

- Royal Chariot Procession from Amarna - Metropolitan Museum

- Fragment of a limestone offering table found at Amarna with the cartouches of Akhenaten - Petrie Museum

- Head of Akhenaten, trail piece from Tell el Amarna - Petrie Museum

- Part of a Limestone Stela with the cartouches of Akhenaten, Nefertiti and Aten - Petrie Museum

- Decorated balustrade which edged a ramp, with Royal cartouches - Rosicrucian Museum

- Calcite fragment of a lintel, cartouche in the corner - Rosicrucian Museum

- Relief of Akhenaten from Amarna - Rosicrucian Museum

- Amarna, desert scene with Gazelles with the eastern hills - Rosicrucian Museum